La Photo – The Francis Usai Letters

Discovery of the private letters of a French airman in Britain. One of the largest wartime collections in France.

The Beginning

Prior to the fall of France on 22nd June 1940, French Air Force personnel and their serviceable aircraft had pulled back to Oran in Algeria in order to re-group for the fight ahead, but in a matter of days the Armistice with Germany was declared and on 10th July the Third Republic was dissolved and Maréchal Pétain was granted full powers by the National Assembly to form a new collaborative government in Vichy. The fighter and bomber groups of the French Air Force, were to spend the next 29 months under German supervision, allowing them only 4 hours a month flight training time in their obsolete Leo 45 medium bombers.

On 8th November 1942, « Operation Torch » saw the Anglo/American invasion of North Africa which released French combatants from Algeria to re-join the Allies. Almost immediately the French Air Force bomber squadrons were able to fly their old aircraft with the Royal Air Force on attacks against German positions in Tunisia. As one French pilot said “we could not wait to put real bombs in our aircraft, and show the British our will to fight, despite our antiquated aircraft and lack of training.

Eventually the first French airmen were re-grouped and left Algiers in high spirits for Britain, with the knowledge that they were to train in new British four-engined heavy bombers. RAF Bomber Command already consisted of airmen and women from over 60 nations across the World.

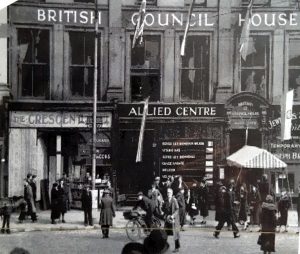

The British Council “House”, Liverpool 1943. The original had been destroyed by Luftwaffe bombers shortly after it opened in 1940.

The first French airmen sailed into Liverpool on 9th September 1943 and on the dockside at Liverpool to greet them was the Allied Reception Centre of The British Council. This catered for around 6000 people per week and had been placed there to welcome Czechs, Poles, Belgians, Russians, Americans, French and many other nationalities who had come to Britain since 1940 to help liberate Europe. It was at this reception centre that two young Frenchmen met and fell in love with two British girls who spoke French and helped to serve tea and cakes to the arriving soldiers, sailors and airmen.

Air Gunnery Training at Evanton, Scotland – Francis Usai is in the centre on the 2nd row.

Retraining was essential with different aircraft and equipment as well as radio procedures and navigational controls. This was necessary as the RAF missions were often on a scale unknown to the French, and included up to a thousand aircraft at once. Plus with over 1,500 airfields in constant operational use across Britain – and all speaking English – retraining was clearly very necessary.

Two Handley Page Halifax bombers of 346 Squadron “Guyenne” near York

Like all airmen, they were split into their roles and duties, with pilots, navigators, radio operators, bomb aimers, gunners and mechanics all distributed to the various specialist training establishments right across Great Britain. Eventually, after months of specialist training they undertook flying training and were grouped into aircraft crews. The largest bombers were the “heavies”. The Lancaster, Halifax and Stirling. Each had a minimum of 7 crew.

Following the escape from Dunkirk in 1940, the war against Germany and her Axis allies in mainland Europe could only be fought from the air and in the early years the mainly obsolescent aircraft available to the Royal Air Force at that time accounted for a terrible loss of experienced aircrews against a more sophisticated and experienced enemy. From the beginning the Royal Air Force told all their bomber crews that they had a realistic 50% chance of survival and all aircrews were volunteers as opposed to other services which were generally conscripted. So, right from the outset, the aircrews were given the choice if they wished to continue with a chance of one in two of being killed – not good odds, but none refused. By the end of the war in 1945, the Royal Air Force were to lose over 70,000 airmen killed with 57,205 of these from the bomber squadrons.

So it was, that in May 1944, after months of intesive training French airmen eventually arrived in the North Riding of Yorkshire, where they reformed their original two Armée de l’Air bomber groups 2/23 & 1/25 into No. 346 Squadron “Guyenne” and 347 Squadron “Tunisie” on 16th May and 20th June 1944 at an RAF base near York. These sole French Heavy Bomber Squadrons were to fly the latest Handley Page Halifax four-engined heavy bombers and night after night they would perform dangerous missions over heavilly defended enemy territory from before D-Day to the attacks on V1 & V2 rockets sites and onto the Battle of the Ruhr – the most heavily defended place on Earth. The physical and mental pressure upon these young airmen was immense and by the end of hostilities the two French Squadrons lost 51% of their airmen and 41 aircraft in just 8 months.

The Letters

In December 2009, Geneviève Monneris and Ian Reed were searching for documents and photographs for a film Geneviève was making about French airman Sgt. Henry Martin and his young English wife, Pat. (See attached article « Flightpaths »)

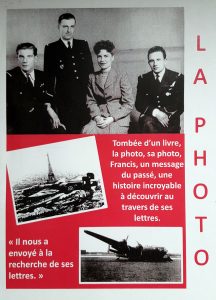

By an extraordinary series of coincidences they discovered an old damaged photograph, showing a young lady surrounded by three French airmen. On the reverse was written the date and the names of Henri and Pat Martin, Jacques Leclercq and Francis Usai.

(photo : l to r ; Sgt. Jacques Leclercq (KIA 02/01/45); Sgt. Henri Martin (KIA 04/11/44); Pat Martin (SOE Agent); Sgt. Francis Usai (injured 02/01/45).

The photograph taken in York on 3rd October 1944, lead them to the discovery of one of the largest collections of letters (in French) from WWII and, thanks to that correspondence, to the discovery of a tragic but fascinating and intertwined story of these four characters and the girl to which it was sent. A story which still resonates today.

With the photograph was a note, dated 1995, and the address of a lady living in Western Australia. The chances of this, now elderly, lady still being there after 14 years was small, but they wrote to her and just a week later, received a reply.

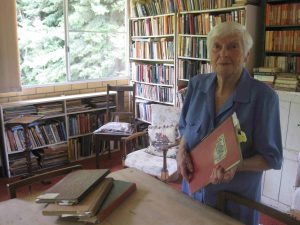

The lady was Mrs Barbara Harper-Nelson (née Rigby) and, as an 18 year old university student learning French, she had met Francis when he arrived by ship at the port of Liverpool with aircrew reinforcements for the two French Squadrons 346 Guyenne and 347 Tunisie. She became his girlfriend throughout the War and from our first contact in 2009 with “Barbiche” as Francis nicknamed her, the hundreds of letters of Francis Usai, which she had meticulously kept for many decades, were revealed to us.

Barbara and Francis 25-10-1944

From an academic and historical perspective, the 360 letters (some 11 pages long) are probably one of the largest wartime collections of their type, and on behalf of Mrs Barbara Harper-Nelson we were eventually able to formally present the originals, which encompassed over 2000 pages, to the Director of Service Historique de la Défense (French National Military Archives) at Château de Vincennes, Paris, to become part of the French National Collection.

Barbara Harper-Nelson (née Rigby) with her diaries, at her home in Lesmurdie, Western Australia in 2011 – you can see a video of Barbara speaking about Francis and the Letters in 2011 – below.

The added value of these almost daily accounts of life and love in wartime, was that Barbara had also kept a daily diary, so that there was in effect a two-way conversation available to us. As a love story, Francis’ letters and Barbara’s diary, gathered together after 67 years, were emotional, humorous and thought provoking. As a young 21 year old typical Marseillais he had a particularly exuberant character and was playful and funny, which comes out in the many events and « scrapes » they got themselves involved with, even though Francis’ regular experiences as a mid-upper gunner in a slow and vulnerable Halifax heavy bomber, were not such fun, especially when operating over the heavily defended Ruhr area of Germany. As with all the RAF bomber crews, the French squadrons lost 50% of their crews in a few short months, and due to wartime censorship, Francis had to keep all the details and the horrific casualties to himself.

The crew of Halifax G for Georges: Top from left to right : Sgt-chef Antoine Morel (wireless operator), Sgt Guy Dufaure (flight engineer), Sgt Francis Usai (mid upper gunner). Bottom from left to right: Sgt Jacques Leclercq (pilot), Lt Daniel Cottard (captain, navigator), Adjt Antoine Adaoust (bomb aimer), Sgt-chef Henri Aubiet (rear gunner). No. 347 “Tunisie” Squadron RAF.

Francis and Jacques were best friends. On 2nd January 1945, Jacques (aged just 20) was killed and Francis permanently damaged his right leg after being shot down by US Forces en route to a mission over Ludwigshafen, Germany. Jacques last words were “…..is Francis OK?“

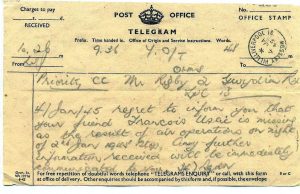

4th January 1945 – telegram to Barbara’s father (Francis’ registered next of kin) – “we regret to inform you…..”

As a social history document the letters are highly significant. This story tells a fascinating account of a foreign airman exiled in Great Britain whilst his country had been invaded, his thoughts and aspirations for a free France and a free world.

Barbara’s diaries complete the other side of the story and recall a fascinating viewpoint of a young British university student amidst those tragic events and daily life living in wartime Liverpool, which suffered from regular and heavy bombing. Their personal perspective on the main events and daily life, from 1944 to early 1946, particularly strikes a chord with us today.

Almost immediately, Geneviève began to edit the letters, translated into English by Michel Darribehaude (also the child of a 346 Sqd veteran) at l’Université du Sud Toulon Var.

The Book

Barbara worked closely with Geneviève and Ian until she died in 2016.

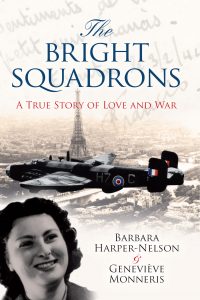

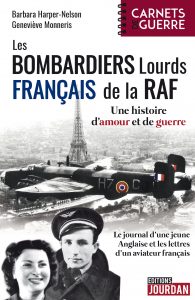

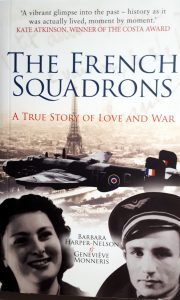

Geneviève’s perseverance and meticulous hard work eventually brought together the letters and diaries into a fascinating 282 page book, first published in English in 2014, entitled “The Bright Squadrons” in hardback cover. The title was Barbara’s own idea and a quote from “The Ministry of Angels” by the 16th century poet Edmund Spencer.

In 2016 a second edition was renamed “The French Squadrons” for the paperback version (Amberley Publishing) and the book was also published in French as « Les Bombardiers Lourds Français de la RAF » (Éditions Jourdan).

Extract of Barbara Harper-Nelson’s interview with Geneviève Monneris, Australia 2011

The Play – “Cis & Barbiche”

Jenny Davis is a successful actress and theatre producer in Perth, Western Australia, and was already an acquaintance of Barbara. She was fascinated to read the manuscript of the book and found the contents so absorbing that she decided to write a new play. Her production, “Cis & Barbiche”, first toured Australia and in 2014

Barbara Harper Nelson with actors Marc Desebrock (Francis) and Jo Morris (Barbiche) from the play “Cis & Barbiche” by Jenny Davis. Perth S.W. Australia – 1st March 2014.

The “real” Barbiche is introduced on-stage to the audience – Agelink Theatre, Perth. Barbara with Jenny Davis and the cast of “Cis & Barbiche” in 2014.

The play “premiered” in Britain at the Theatre Royal in York in July 2014, to coincide with the Grand Départ of the Tour de France in the City. The previous evening a Gala Dinner named “La Grande Soirée des Officiers Français” with musicians from Paris, celebrities, civic dignatories and French military officers had taken place next to the theatre in the 18th Century state rooms in York which had been used by the very same French airmen for their dances in 1944/45. It was at this occasion which corresponded with Francis’ famous omen:

“In seventy years … people will talk about Barbiche who saw England invaded by all those weird foreigners who stole girls’ hearts”

……..a prediction which came true exactly 70 years later!

The cast of “Cis & Barbiche” at The Theatre Royal, York – 3rd July 2014

La Photo – a “docu-lecture” series

La Photo (Love in Times of War) is a « docu-lecture » about the Francis Usai Letters and Barbara Harper Nelson’s Diaries. It first took place at Institut Français, South Kensington, London in 2019 with actors, original film footage and professional academics who discussed the background to the story, the historical significance of the documents and the problems of writing under wartime censorship.

The event was produced by Dr. Alice Béja, Higher Education and Research Attachée at the French Embassy, London.

Supported by :

The French Embassy, London; The British Embassy, Paris; Institut Français;The British Council; The Royal Air Force; Armée de l’Air; Association de l’Ordre National du Mérite; Service Historique de la Défense; Association des Anciens et Amis des Groupes Lourds; The Royal Air Force Association and Fondation de la France Libre.

La Photo – introduced by French Cultural Attachée, Mme Claudine Ripert-Landler, with Ian Reed, Geneviève Monneris, Dr. Mona Parra (Historian, University of Grenoble and Member of ILCEEA4) and Prof. Claire Gorrara, Professor of French Studies, Cardiff University – 30.04.2019

Contact via: https://afheritage.org/contact for more information.

Sgt. Francis Usai (21) – mid upper gunner

In his letter to Barbara written from his hospital bed on Victory in Europe (VE) Day, 8th May 1945, and thinking of their young friends who have died in the previous weeks, Francis tries to come to terms with what Victory really means:

“Et voila! But I can’t feel any joy or anything; I haven’t the impression the war’s over, and in any case it’s not. Millions of people have stopped suffering, and this makes me happy, but I can’t feel enthusiastic; it seems to me I ought to have shouted for joy, or burst into song, but I only wept for a moment when the armistice was announced. It’s true that I hadn’t dreamt of spending V-Day in hospital. Since the war began, I’d dreamt of flying over the Arc de Triomphe on such a day. But I have to remember that the poor soldiers in the Far East are in a much worse situation than mine. Some died yesterday and the day before. They’ll never return to their own country, while I still have that hope. But I confess I felt rather melancholy when I saw the village all lit up and heard the singing and the shouting. I ought to have been happy, since everyone else was. You, too, must have been very happy, but I couldn’t help it; the ward was so quiet, so empty, there were only three of us, the rest were in town, and it wasn’t envy, darling, but rather despair. I wished you’d been by my side, and then I might have cried, but it would have done me good. I just can’t begin to explain and analyse all the strange, complex and paradoxical feelings that troubled my mind during those two days. It was some sort of astonishment mixed with joy, but above all this a kind of melancholy.”

Francis died in 1996.

Keeping the Memory Alive

Today: the Groupes Lourds Memorial on the D-Day landing beaches at Grandcamp Maisy, Normandy, commemorates the two French Heavy Bomber Squadrons based near York. The location was one of their very first operational missions over their own country on the night of 5/6 June 1944 to silence the guns at Maisey Battery overlooking the Landing Beaches.

© Geneviève Monneris & Ian Reed – 2020