The Battle of Britain – 80th Anniversary – Never has so much been owed…

The Battle of Britain Speech by Ian Reed at the British Ambassador’s Residence in Paris on 15 September 2020.

Guests included: the Ambassadors of Britain, Belgium, New Zealand and Ireland; Chief of Staff of the French Air Force and senior diplomatic representatives from Poland, Canada, Slovakia, Australia, South Africa, Germany, Eire, U.S.A., France, Czech Republic, UK plus the Director of the Ecole de Guerre and the representative of the French President.

Speech with additional photographs……….

« Si le destin ne m’accorde qu’une courte carrière de combattant, je remercierai le ciel d’avoir pu donner ma vie à la libération de la France. Qu’on dise à ma mère que j’ai toujours été très heureux et reconnaissant que l’occasion m’ait été donnée de servir Dieu, MON PAYS et CEUX QUE J’AIME, et que, quoi qu’il arrive, je serai toujours près d’elle.» (words spoken by Général Philippe Lavigne)

‘If Fate allows me only a brief fighting career, I shall thank Heaven for having been able to give my life for the liberation of France. Let my mother be told that I have always been very happy and thankful that the opportunity has been given me to serve GOD, MY COUNTRY AND THOSE I LOVE, and, that, whatever happens, I shall always be near her.

Cmndt René MOUCHOTTE – killed in action 27 August 1943.

Cmndt. René Mouchotte DFC RAF. 1914 – 1943

These fateful words are by one of France’s most famous fighter pilots who flew with the Royal Air Force from airfields across Britain during those dark days following the fall of France. His words exemplify the thoughts of that relatively small band of young men who came from countries across the world to Britain, which now stood out alone as the last defence against the NAZI onslaught. They were young men who simply did not know whether they would be alive the next day, but utterly convinced that what they were doing was the right thing.

After 6 months of the Phoney War / « Drôle de guerre », when little happened apart from the sharing-out of Poland between the USSR and Germany, the inevitable blow came, as many had predicted, on May 10th when German forces invaded the Low Countries, entering French territory just 2 days later.

Luftwaffe Do17 medium bomber

Despite German forces being in a poor strategic position following the occupation of Poland, in fact, “a hopeless strategic position” according General Franz Halder – Chief of the German General Staff, the completely unconventional tactics designed by Manstein and Guderian, thrown out by the General Staff but picked up and given the go-ahead by Hitler, had the desired effect and threw the British and French forces off balance, leading to the debacle of Dunkirk and the advance across France.

Messcherschmitt 109 fighters – out performed the Huricane and Spitfire in the early stages of the Battle

The war in the air had been equally destructive. On a single day (11th May), nearly 20 French bombers and over 30 British fighter escorts were shot down attacking German crossings over the River Meuse, and on the 14th May, 40 British bombers were shot down. No higher rate of loss had ever been experienced by the Royal Air Force in a single day.

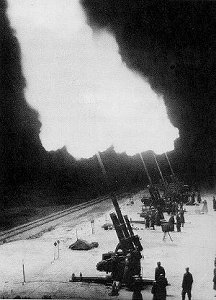

German “88” anti aircraft guns in action

The civilian cost was high too, and huge sad columns of refugees were filling the roads escaping the destruction of their homes, many with memories of just 22 years earlier, were heading west in every form of transport available.

France – 19th June 1940

From 10 May until 11 June, the British and French air forces lost around 1,850 aircraft in combat, of which some 950 were French. However France was not going to give up easily and the Germans had to fight for every inch. But the cost was enormous. France lost over 300,000 people dead, missing and wounded in just 5 weeks.

The end of a British bomber

Suffering major losses the Armée de l’Air made a strategic withdrawal to the French provinces in North Africa to re-group whilst politics moved fast in the following days and to many people’s dismay, an Armistice was announced on June 22nd. But many young French airmen were determined not to give in.

Whilst around 1500 French aeroplanes were now withdrawn to Oran, the terms of the Armistice meant that most had been disabled and the airmen detained, except for a precious few who manage to escape to England.

Louis Hervelin, a young French airman from Bayonne who had been detained in Oran told me, “it is wrong to think that we had all just given in. It was the most frustrating time of our lives. Of course we wanted to fight on but how could we do this with no aeroplanes that worked? Everyone I knew felt betrayed by the lack of leadership, so we were condemned to sit tight and practice with the little resources we were allowed, and to pray that we would soon be given the chance to get our country back again”.

Louis would have 3 long years to wait, terrified to learn that his 18 year old fiancé Berthé, back in Bayonne, had just joined the Resistance – and was to be arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo some months later.

The eyes of the world now turned towards Britain with a resignation that it too would fall soon.

The Battle of Britain was the first “air battle” in history, it was also the first battle to have been named before it began, when on June 18th, the day of De Gaulle’s famous “l’Appel” to the French nation, Churchill made his famous “Finest Hour” speech and announced that “The Battle of Britain is about to begin”, in fact it didn’t begin for about another four weeks, but no one seemed to doubt that Hitler would invade.

Meanwhile back in France amongst the refugees, 12 year old Suzanne Calmel from Paris, with her mother and younger sister had been stopped by the Wehrmacht as they travelled west towards Bordeaux.

At the Front, her father (an officer in the French Army) had sent a message to the family in Paris to leave as soon as possible. They had black Citroën Traction Avant, but Suzanne was the only one able to drive (she had learnt, sat on her father’s knees). With several cushions, the 12 year old assisted by her mother with her sister in the back set off west.

France – June 1940

En route they were overtaken by the advancing Germans and turned back. They eventually took shelter in a flat in Chartres, where, every day, the two young girls would creep up to the attic at the top of the house overlooking the airfield and watch the German bombers take off.

She relates, “You cannot imagine the hurt, seeing foreign soldiers laughing and drinking in our French streets every day, when we are all held indoors under curfew. Radios were confiscated but as we saw or heard the bombers take off, everyone knew it was poor England’s turn next”.

Home Chain Radar Station

Britain did have one secret weapon up their sleeves however. It was the first country in the world to have a functioning ringed radar defence chain connected to a centralised air force command and control structure. One German pilot later wrote in his diary, “you just can almost never surprise them”! Yet when the last Hurricanes left France on 21st June, RAF Fighter Command was at rock bottom. It had lost about 450 fighters and 460 pilots in just 6 weeks.

RAF Fighter Operations Centre

Had the Luftwaffe simply carried on, it would have been a different story, but the Germans too had suffered heavily in France. Field Marshal Kesselring later stated; “The uninterrupted battle of our air force beginning on May 13th had literally spent the personnel and the material. After three weeks of combat, our air force units had fallen to 30% and even 50% below their theoretical effectiveness.”

From 17th July to 12th August Attacks increased with larger daylight raids against shipping in the English Channel, plus ports along the South and East coasts and some coastal airfields, with increased night attacks against the West, Midlands, and East Coast, especially RAF facilities and the aircraft industry. The RAF pilots gave as much as they got.

Junkers JU88 “Stuka” dive bombers focused on the Home Chain Radar stations – although initially successful in the early stages of the war in Europe, they were no match for the Hurricane and Spitfires and lost large numbers in the early stages of the Battle of Britain.

In the background RAF Bomber Command and RAF Coastal Command were relentlessly flying into enemy territory every day and suffering heavy casualties, to disrupt airfields, communications and shipping.

Heinkel HeIII

The RAF pilots fought “with their backs to the wall”, and this was especially true for the 595 pilots who had come to Britain from 13 countries across the world.

“Scramble” as other pilots push a Spitfire off the grass on to the runway

The historian and author Len Deighton put it succinctly when he wrote of the foreign pilots: “These homeless men, motivated often by a hatred bordering upon despair, fought with a terrible and merciless dedication.”

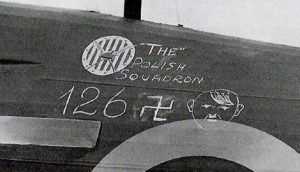

No. 303 Polish Squadron RAF – 145 Polish airmen fought in the Battle of Britain

“Adler Tag” the day planned for the major battle to overwhelm the RAF as a prelude to “Operation Sea Lion” – the seaborne invasion, had been originally set for early August but postponed several times as German air assaults were rebuffed.

Luftwaffe Dornier Do17 “Flying Pencil” medium bomber- 1940

13th August to 6th September saw large-scale attacks night and day against RAF airfields in South-East England, with the object of destroying the RAF’s ability to provide a defence. The situation was becoming desperate.

Heinkel He.111 Bombers

On 15th August, “Black Thursday” 1120 German aircraft attacked airfields in the SE and 211 aircraft from Scandinavian bases attacked the NE of England and Yorkshire. But the Luftwaffe loses 98 aircraft and fails to make a breakthrough.

“One less to worry about”! A Messerschmitt 109 shot down over Britain.

Back in the attic in Chartres, young Suzanne Calmel and her sister watched as the German bombers took off for England. “As we watched the aircraft every evening, something strange began to happen. We saw that not all would return, and some that did were on fire or badly damaged. Every day it got worse and worse for them”.

9 days later on 24th August, and strictly against orders, several Luftwaffe bombers which had become lost, dropped their bombs on London. Churchill retaliated the next night by sending 40 British bombers on their first offensive raid to Berlin. Suddenly on the 7th September the Luftwaffe shifted to large-scale day and night attacks against London and other cities.

St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London stands out above the flames and smoke during the London Blitz – 1940

This date is viewed by many as the day when the Battle was lost, as the brief respite it gave the southern airfields and the few days grace it gave the RAF to regroup was just enough to bring Fighter Command back up to strength.

RAF pilots “Scramble”!

“Adler Tag” eventually came to a head on 15th September, Hitler’s final deadline to the Luftwaffe. Frustrated at not making the desired impact on British air defence, the Luftwaffe launched a huge aerial offensive, but the industrial and technological advances made throughout the summer meant that the RAF fighters now outnumbered the Germans for the first time, and they were already waiting for them in their new large “Wing” formations.

RAF Hawker Hurricanes – part of the “Big Wing” – 1940

By the end of the day it was announced that 183 German aircraft had been shot down, although the actual figure is probably around 60, but it was still over double that of RAF losses, and two days later Hitler secretly postponed Operation Sea Lion, the Invasion of Britain.

Now aged 93, Suzanne continues, “Day after day we noticed that fewer and fewer Luftwaffe aircraft returned, until one day, none returned at all. The RAF were standing up to them. To this day, I cannot tell you the hope and joy this brought to us, that poor France was being revenged and for the very first time we all just knew that Germany could be defeated.

A Heinkel HeIII bomber formation receives fire from British fighters over the English Channel – 1940

Aerial attacks continued from 3rd to the 31st October by Luftwaffe and Corpo Aereo Italiano aircraft, but with bad weather, daylight attacks were on a much smaller scale while large-scale night attacks continued mainly against London. This was the start of what came to be known as the ‘Blitz’ against ports and cities across Britain which lasted until May 1941, but the Battle of Britain was over.

The dockyard areas by the River Thames in East London received significant damage

The RAF records 2,937 pilots as having officially taken part in the Battle between July 10 and October 31, 1940. Of these:

544 killed in RAF Fighter Command; 718 killed in RAF Bomber Command, and 280 killed in RAF Coastal Command, a total of 1,542.

Over the same period the Luftwaffe lost approximately 2,500 aircrew killed, with almost 1,000 taken prisoner, mainly those who ditched in the Channel. Similar RAF pilots could be rescued and often went straight back into active service.

The rest is history as they say, and although much has been written about the strategic value of the Battle of Britain, in the end there is an inescapable truth that for three months during the hot summer of 1940 the front-line defence of free Europe was all in the hands of a just few hundred largely inexperienced young fighter pilots against a larger and experienced invading force – and the world had held it’s breath.

Although just 13 French fighter pilots are credited with taking part in the Battle, it is without doubt that the heavy price paid by the Armée de l’Air during the Battle of France which left the Luftwaffe in a far worse state for continued operations had enabled Britain to recover sufficiently to stem the tide – but it was a close run thing.

RAF Old Sarum 1940 – some of the Free French pilots who fought in the Battle of Britain

As for Louis, he got to Britain in 1943 and trained with the RAF. He flew with one of the two French Heavy Bomber Squadrons with RAF Bomber Command and took part in the attacks against coastal batteries in Normandy on the night before D-Day and onto Germany, achieving his vow to help free his beloved France. He found Berthé again in 1945 and married her. She had worked in the City Hall in Bayonne and had been arrested for forging identity documents for escapees, refugees and resistants, helping them escape over the Pyrenees into Spain.

Louis and Berthé were married for 73 years.

To all of them we owe a great debt.

15 September 2020

15th September 2020 – the annual ceremony at the tomb of the unknown warrior beneath the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. The British Ambassador, Lord Llewellyn of Steep, alongside Madame Geneviève Darrieussecq, Minister responsible for Military Commemoration and Veterans Affairs. Behind, Group Captain Antony A McCord, British Air Attaché and Air Commodore Tim Below, British Defence Attaché.

https://twitter.com/i/status/1306964089210634241

15 September 2021

Ian Reed laid the Allied Forces Heritage Group /GPFA wreath at the Arc de Triomphe with Mdme Geneviève Darrieussecq, French Minister for Remembrance & Veterans; British Ambassador HE Menna Rawlings and Air Marshal Sir Graham Stacey RAF. The event was attended by representatives of other nations and was accompanied by troops and orchestra of 2nd Blindée (Armoured) Division “Lcclerc” (the French division which liberated Paris in 1944)