A Polish Corporal’s Journey to Monte Cassino – Christopher Cytera.

The despoilation of Poland, and a young soldier’s extraordinary journey to join the Allies and General Anders Army in Italy.

Ludwik Cytera was born on 16th July 1913 in Rudka, 80km north of Lwów in pre-war Poland, now western Ukraine.

Ludwik Cytera – Polish II Corps – 22nd March 1943

He was my grandfather and this is his story. Although he never talked to me about it, in fact he did not even tell it to my father, his only surviving son, so it is a story which I have pieced together through historical accounts, old photographs and from other members of my family.

Although I did not realise it at the time, one of my last meetings with him led me to piece it all together some 25 years later thanks to the landmark work “Trail of Hope” by Norman Davies, which by his planting a seed of thought in my mind, led me to it. I am sure that this is what he intended me to do, so that I could tell his story in a way he could never bring himself to do.

“Rosja zawsze będzie wrogiem”

The only part of this story which my grandfather ever said to me directly was this statement: “Russia will always be the enemy”. I was in my 20s at the time, and rather puzzled by it.

As for why our family ended up in Great Britain, I had just been told by other Polish members of the family, that “the Russians had formed a Polish Army”. The truth, I found, was very different. However, my grandfather’s antipathy towards Russia did stick in my mind, his words repeatedly coming back to me as time unfolded.

Time-line to Invasion:

28th June 1919: following the Great War, the Treaty of Versailles ceded former German territories in West Prussia, Poznan, and Upper Silesia to Poland creating huge resentment in Germany.

26th January 1934: The resurgent Germany under Hitler signs a non-aggression pact with Poland, aimed at calming nerves in Paris and London regarding the “Polish Corridor”.

31st March 1939: Hitler’s invasion of the Rhineland; annexation of Austria and the breaking up of Czechoslovakia in violation of the Munich Agreement, pushes French and British patience to the limit and a pledge to support Poland is made.

23rd August 1939: Secret pact between Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR) to invade and partition Poland between themselves.

25th August 1939: Agreement of mutual assistance signed between Britain and Poland. Hitler cancels initial plan for invasion on 26th August as a result.

1st September 1939: Hitler invades Poland and on 3rd September, Britain and France declare war on Germany – World War Two has begun.

17th September 1939: the Soviet Union (USSR) invades Poland from the East in accordance with the “Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact”.

USSR Minister Molotov and NAZI Foreign Minister Ribbentrop seal Poland’s fate – 23rd August 1939.

In 1932 aged 19, my grandfather took his first job at a concrete panel manufacturing company at Radziwiłłow (now Radyvyliv, Ukraine) around 100km east of Lwów. Then, in 1935 he became an administrator and gamekeeper at a national forest in the Wołyn region (now Volyn, Ukraine). He married my grandmother, Adela and they had two sons, my father Mieczysław and his baby brother Józef.

As the international situation deteriorated he was drafted into the Polish Army on 31st August 1939, shortly before the invasion, but his brief service ended abruptly on 27th September as Poland was overrun from two sides.

London Evening Standard – 1st September 1939

German Troops invade Poland on 1st September 1939

They were living near a town called Łuck at the time, pronounced more like “Wootsk” and not lucky at all. From there they were captured by Soviet troops and eventually deported to a slave labour camp in the Molotov Oblast of Russia, over 1500km from his home. This was the beginning of a brutal and massive social and ethnic cleansing operation by the USSR.

Civilian houses in nearby Dubno were machine-gunned, according to eyewitness accounts. Descendants of those who were there, testify to bodies hanging from lamp-posts in Lwów and babies who cried in deportation trains being shot in the head.

Soviet Troops invade Poland – 17th September 1939

Every organ of the reborn Polish state of 1918, a much more successful, prosperous, democratic and tolerant one than the USSR, was destroyed. Anyone connected with the state, such as teachers or policemen were declared “enemies of the people” in show trials, and forcibly deported to slave labour camps (gulags) over 13,000km away in deepest Siberia.

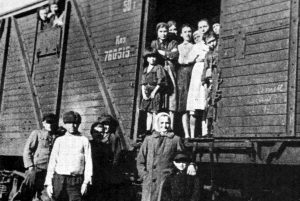

Young and old were forced to leave their homes

Simultaneously attacked from the west by Nazi Germany, and from the east by the USSR, Poland collapsed. 22,000 Polish officers were captured and later massacred in cold blood at Katyn in an unspeakable war crime which successive Soviet governments tried to cover up until the eventual collapse of the USSR fifty years later.

Poland invaded from East and West – September 1939

Between 1939 and 1941 the USSR invaded and oppressed six other countries under the auspices of the “Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact”. Over 1.5 million Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Finns, Belarusians and Jews were captured and exiled.

German Luftwaffe bombers attack Warsaw.

These people suffered appalling conditions, mostly in Siberian gulags, with the majority dying of hunger, disease or cold, during their first Siberian winter. Poland was carved up between the two brutal dictatorships and eradicated from the map.

Wehrmacht troops advance across Poland – September 1939

The eastern part of Poland known as the ‘Kresy’, with its two main population centres being Lwów in the south (now Lviv in Ukraine) and Wilno in the north (now Vilnius, Lithuania) came under Soviet control. Libraries were burned, the Polish language banned and all Polish laws and legal structure abolished.

German and Soviet troops meet up as they overrun Poland – September 1939.

A fledgling democracy, which had introduced votes for women in 1918, had been crushed and replaced with totalitarian dictatorships in just a few short weeks and the ethnic cleansing by the USSR consisted of four mass deportations during 9/10 February, 12-13 April, 25-30 June 1940 and 14-21 June 1941.

My grandfather and his family were victims of the second deportation. His record shows he was arrested with his wife and young family and eventually deported from a small place called Rowne (now Rivne) in the neighbouring Oblast. This must have been the transit point: a modern map shows it only 74km from Łuck where they lived.

Mass deportation of Polish civilians 1940 – 41

My father was only three years old at the time. His earliest childhood memory was of somebody knocking on their door in the night and saying something in Russian to the effect that they only had a few minutes to leave.

Their ordeal is likely to have been similar to that of Teresa Kalinin, who also had a gamekeeper father, and whose account of deportation to the exact same slave labour camp is as follows:

“Before the war my father was a gamekeeper, we lived in the colony of Ożynnik near Studzianek (…) At the end of October [1939] they released him from work and told us to leave the cottage. In March 1940, the Soviets knocked at the window with a shout to open quickly. There were three of them, one stayed in the yard by the sleigh, the other stood in the hall and the third went into the apartment and ordered the whole family to pack, including my sister Jadzia aged 4, and the youngest Danusia, 20 months. Mama started to dress us, she made beds (…) One of the soldiers started shouting that we should pack everything we had. Father asked: ‘Why? He said, ‘You will sell it for children’s bread, maybe you will survive somehow.’ When the parents still did not take anything, he packed things himself and brought them onto a sledge. Grandma, mother and all of us cried, and my father cursed what the world is standing in. When, in addition to the furniture, they brought everything out, they told us to sit on a sleigh. There was 40 degrees of frost. They transported us to Białystok and unloaded everyone in Zwierzyniec, where there were a lot of Poles. In April, they packed everyone in cattle wagons and sent them on their way”

Civilians were piled into cattle trucks for the long cold journey

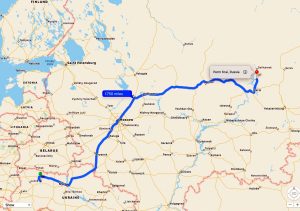

My grandfather and his family were taken as slave labour to a logging camp in the Molotov Oblast, USSR where they arrived on 23rd May 1940. This area is now known as Perm Krai. The labour camp was called “Diedowka” (in Polish) and was located in Gaynsky District.

Soviet Labour Camps for deported populations of invaded countries

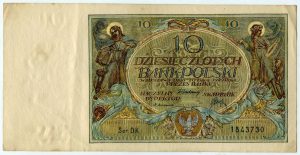

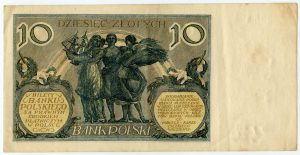

The lack of any family documents from this time suggests that all they had with them were their clothes and these beautiful Polish banknotes which were soon to become worthless.

Pre 1940 Polish 10 zlotych banknote

They travelled via cattle trains to Perm Krai, in appalling conditions. People were crushed together standing in their own urine and excrement for weeks. They had no room to sit down, and those on the outside of the wagons found their hair frozen to the walls if they fell asleep against them. Many died on the way, but my grandparents and their young family survived this part of the journey. They were luckier than most in that they were not separated, and that the distance of over 1500km, though far from home, was not as far to travel as those other unfortunates who were sent all the way to Siberia.

Polish civilian families were deported over 1500km to labour camps in the Soviet Union

They spent around two years in the “Diedowka” at Perm Krai. Neither of my grandparents ever mentioned their ordeal there to me, although my father had a recollection of someone going to sleep under a table and never waking up again.

It is unimaginable how they suffered slave labour under conditions of extreme deprivation and disease. We know from other accounts that if prisoners did not fulfil their quota of work, they were fed less. As far as the Soviets were concerned, killing the less able slaves through starvation was a cost-effective way of selecting the more able workers.

Soviet Forced Labour Camp in the 1940’s

The only thing surviving from their two years at this slave labour camp is a photo of their younger son Jozef. He is being held by a man in winter clothes, probably my grandfather. He looks about 8-12 months old, so this was probably taken in early 1941, about half way through their time at the Diedowka camp. Perhaps he is holding a flower on his first birthday? It is the only family photograph of Jozef and the only photograph from the whole of their two years in the Soviet Union. It was probably taken illegally at the same time as photos for Soviet ID documents, as we know from other accounts exhibited at the The Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, Poland.

Jozef Cytera 1940-1942

Escape from the USSR

History changed when Hitler invaded Russia on 22nd June 1941. With his erstwhile ally now threatening to annihilate the USSR, Stalin was forced to collaborate with Great Britain. But although the USA would not enter the War for another 6 months, the British Empire was not quite alone.

Both the exiled French and Polish governments were based in London, and the latter had already supplied 30,000 highly skilled military personnel who had escaped Poland, the only invaded country not to have surrendered.

General Maczek’s 1st Polish Armoured Division was stationed in Scotland, the Carpathian Brigade in North Africa, and around 8000 Polish RAF personnel, including the famous 303 Squadron, had made all the difference in the Battle of Britain.

The change in circumstance therefore impelled Stalin to the release the Poles from the Gulags and to form an army to fight the Nazis. He called it an “amnesty” to deflect attention from his hostile invasion and treatment, and also to give the false impression that Poland had been the aggressors in the first place.

Stalin’s duplicity to the arrangement resulted in more Polish deaths as they had to make their own way hundreds of kilometres to army recruitment camps in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The gates of the gulags were opened, but nobody was informed where the army recruitment centres were or how to get there. However some made it, including my grandfather Ludwik and his young family.

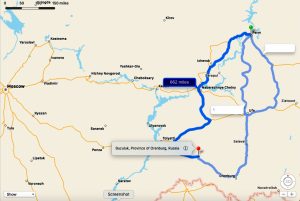

The “escape routes” out of the USSR 1941/2

Research has determined that Ludwik’s regiment was formed at Kermine in Uzbekistan after released prisoners first travelled to Buzuluk. We do not know how they got there, or how they found out where to go, but it is likely that they had to travel some or all of the 1000km on foot. Perhaps they managed to hitch rides on horses and carts or sell belongings to get train tickets? The very fact that they travelled this journey and survived, especially with baby Jozef who was only just over two years old at the time, bears testimony to their determination, resourcefulness and fortitude.

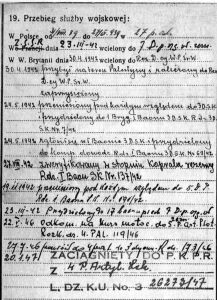

His army record shows that he was enlisted on 23rd March 1942 in the Soviet Union.

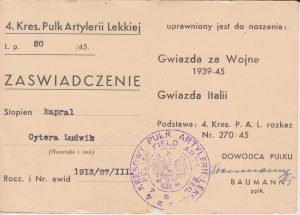

Ludwik’s Polish Army record

The original agreement was that these troops were to fight alongside the Soviets against the Nazis on the Eastern front. However, this “army” was poorly equipped, poorly fed, and clearly not a serious fighting force. All the signs were that Stalin simply wanted to use them as “cannon fodder” on the Eastern Front.

Again, history was to take a different turn as the main character in this extraordinary odyssey entered the scene.

General Władisław Anders

General Władisław Anders

General Anders originally served in the Tsar’s Cavalry in pre-revolutionary Russia, when partitioned Poland did not exist. He thus spoke Russian and understood the Soviet mindset. He was also captured by the Soviets when they invaded Poland, but instead of being murdered at Katyn with the rest of the officer class, he was instead imprisoned and suffered torture, regular beatings and intense interrogation at the notorious Lubianka prison in Moscow.

He was released in 1941 as part of the deal with Britain, and put in charge of forming the Polish Army within the USSR.

What he saw shocked him: malnourished and ill-equipped soldiers dressed in rags, with a suspicious shortage of officers. Even though his men were highly motivated to fight for their country, it became obvious to Anders that they were not going to live long enough in the USSR under the conditions to which they were being subjected.

Anders knew that he first had to save the lives of the men in front of him before he could start to get his country back. His charisma, negotiating skill and knowledge of the Soviet way of thinking enabled him to broker a 3-way deal with Stalin and Churchill, to get them to safety, under British command and out of the Soviet clutches. So they were transported to Persia (Iran) which, after 22nd June 1941 (Operation Barbarossa: the German invasion of USSR) had been occupied by Britain and the USSR to protect the oil fields and access to India from German invasion, and to ensure an Allied supply route into the Soviet Union. Here the Poles would be properly fed, accommodated, trained and equipped by the British 8th Army.

Only an army could mount such a colossal humanitarian rescue operation in those days, bringing large amounts of food, tents and medical supplies to one place. 120,000 lives were thus saved, including those of my grandparents and father, to which we owe a great debt to Churchill who had them released, plus Anders who got them out of the USSR and to the British 8th Army who took them all in.

The Journey to Iran

The Poles were transported from the USSR to Persia (now Iran) in two evacuations, the first from 24th March to 5th April 1942, the second from July to September 1942.

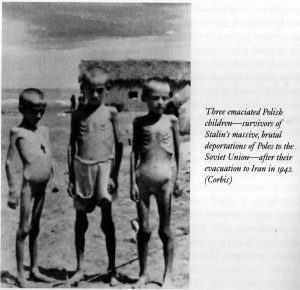

We know from the date of my grandmother Adela’s Polish passport, issued in Tehran on 6th June 1942, that the family must have been part of the first group. This is how my father, by then 4½ years old, must have looked after the family crossed the Caspian Sea and arrived on the beach at Pahlev in Persia:

Emaciated Polish children arrive in British held Persia after a long journey from the USSR

My father told me that he remembered the railway journey towards Tehran, but few details of it. The conditions may have been better than the original deportation journey, as he seemed to recall people being allowed off the train to relieve themselves when it stopped, although some were left behind in the process!

He had no other memories of the gulag, nor the journey out to Buzuluk, nor the ship across the Caspian sea. Apart from these two memories, the photograph of his younger brother Jozef is all that was passed down to us from that period.

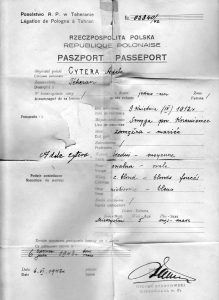

Sadly Jozef did not survive. My grandfather never mentioned him, and my grandmother only said that she had another son who died of cholera in Africa. But this was not true, as we know that he died in Iran. On the right is Adela’s provisional passport, issued by the Polish Consulate in Tehran. How must she have felt when asked how many children she had?

Jozef’s tombstone in Tehran

Adela’s Passport 1942

Their baby son, having survived deportation and the horrors of the gulag for two years, had died just as he got his first taste of freedom. It could only have been a matter of weeks before my grandmother’s visit to the consulate to obtain the passport, and she was probably on her own by then, as Ludwik had been moved to Palestine for training with the army.

From Persia the family were separated, with soldiers’ wives and children sent to safety in various corners of the world from New Zealand to Mexico. Adela and Mieczysław went to Masindi in British Uganda, which my father often referred to as “the best time of my life”. Climbing up the trees to pick fresh mangoes was something he often mentioned, right up to the end of his life.

Training in the Middle East

Meanwhile, now out of Soviet clutches and under British command, a real fighting force could be created. Ludwik’s documents state that he was in the 4th Lwów Light Artillery Regiment and research shows that he would have been stationed at what was then Isdud in Palestine. [4000 Palestinian inhabitants of Isdud were forced to flee in 1948, at the founding of the state of Israel, themselves becoming refugees in the West Bank and Gaza. The Israeli city of Ashdud was founded on the ruins of Isdud in 1956].

Polish II Corps on parade in Palestine – 1942

The passport-style picture at the beginning of this story was taken in Palestine. On the reverse is a handwritten date of 22nd March 1943 and printed ‘Photo Studio “Wera”, 19, Allenby Road’, which is likely to be the famous Allenby Street in present-day Tel Aviv, near the port of Jaffa.

10th August 1942: Palestyna. Kadra Plut (Polish Palestine, Sergeant’s staff)

10th August 1942: Palestyna. Kadra Plut (Polish Palestine, Sergeant’s staff)

The Polish II Corps were then able to exchange these photographs with those from their loved ones thanks to the British Army Postal Service, which must have seemed an incredibly civilised, morale-boosting gift from heaven when compared to the Soviet hell from which they had all just emerged.

The pictures below have inscriptions in Polish on the back. In the second he may be the one marked.

Corps Commanders Parade, Palestine – July 1942

2nd July 1942: Palestyna. Defilada przy dowódcy korpusu – Corps Commanders Parade. Ludwik indicated by arrow

2nd July 1942: Palestyna. Defilada przy dowódcy korpusu – Corps Commanders Parade. Ludwik indicated by arrow

Clearly the troops are much fitter and stronger after proper nutrition and training, a far cry from the emaciated refugees who had arrived in Iran. Contemporary British accounts from 1943 describe troops as, “in good a condition as any in the British Army”.

Deployment into Action

In 1943, the Allies deployed the Polish II Corps, the official name for “Anders’ Army”, to Italy. They were under the command of the British 8th Army, possibly the most multi-national force every assembled, which included troops from New Zealand, Canada, India and the Free French, (mostly Algerians and Moroccans). They were joined by large contingents of USA troops who had now joined the Allied cause.

With fellow Polish officers, Italy 1944. Ludwik is sitting on the step in the centre.

The Allies successfully landed in Italy where, tired of Mussolini and his alliance with Hitler, Italian locals helped the British and Americans onto the beaches in Sicily in July 1943 and southern Italy in September.

The Polish II Corps landed at Taranto on the east coast at the start of 1944 and started to advance northwards. By July 1943 Mussolini had been deposed and the Italian Army was eventually withdrawn whilst Italy became neutral. In response the Germans strengthened the “Gustav Line” right across Italy and the shrewd command of General Kesselring significantly slowed down the Allied advance.

This slow down was exacerbated following the Allied landings at Anzio, where the Americans were slow to break out of the beach head, and after a successful surprise attack over the mountains by General Juin and crack Free French troops, General Clark went against the Supreme Allied Commander’s orders and headed for Rome, missing the opportunity to surround and annihilate several Wehrmacht divisions, allowing the enemy to escape and regroup to fight again further north.

Monte Cassino 17 January – 18th May 1944

The 8th Century Monte Cassino Monastary in the “Latin Valley”, 130km SE of Rome. A fortified position on the German “Gustav Defence Line”.

Aerial bombing of the ancient monastery of Monte Cassino was carried out in the mistaken belief that the Germans were there in large numbers. However, a relatively small number of German paratroopers actually occupied the rubble and used it as perfect cover to inflict casualties and further slow down the Allies advance.

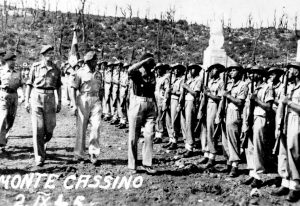

Polish II Corps troops at Monte Cassino.

After three failed attempts to take the seemingly impregnable German position by British, American, New Zealand and Indian forces, it was the Polish II Corps on 16th May which launched the final victorious assault on the position as part of a 20 division assault across a 20 mile Front. On 18th May a Polish flag raised by the 12th Podolian Uhlan Cavalry Regiment followed by a British Union Jack were hoisted above the ruins. A week later the German “Senger” defensive line collapsed. There had been over 55,000 Allied and 20,000 Germans casualties during the campaign at Monte Cassino.

British Army troops advance amongst the rubble at Monte Cassino – May 1944

The significance of this victory over the Germans for the Polish nation cannot be overstated and allowed the Allies to advance further against the Axis forces. The result was that General Anders had cemented the worth of the Polish nation in the eyes of the world. He had proven that Stalin’s claims that Anders’ men had escaped from the Soviet Union because they supposedly did want to fight were untrue, and designed to divert attention from the cruelty and oppression they had suffered under the USSR.

Polish and British Flags fly over Monte Cassino 18th May 1944

Meanwhile the Red Army was sweeping through Poland and onto Berlin by the time the German SS in Italy had surrendered to the Allies. Eastern Europe, especially Poland, may not have fallen under Communist control after the war, had the Allies not been bogged down and had advanced through Italy in, perhaps 12 months instead of 20?

Presentation of colours to Polish II Corps by HRH King George VI and Queen Elizabeth – General Anders centre.

For General Anders and the Polish II Corps, it was too late to save Poland from the Russians by military means alone. How must these Polish soldiers like Ludwik have felt, as they advanced up Italy’s East Coast liberating town after town from fascism, greeted with cheers and flowers, but not being able to liberate their own country from Soviet communism?

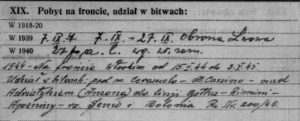

This extract from Ludwik’s army record testifies to his time on the front and the battles he was involved in. Note the references in Polish to Monte Cassino, Ancona and Bologna.

Ludwik’s Army Record mentioning Monte Cassino.

The next two photographs must be from Italy judging by the buildings, possibly Ravenna, near Bologna, where Ludwik studied for his Diploma in telephony.. In the first, Ludwik is on the right on the balcony. In the second he is seated on the step at the front on the right.

Ludwik (r) in Italy 1944

In 1990, one year after the fall of communism I drove my car to Poland. I had been advised to park it in a Parking Strzeżony (guarded car park) to avoid it being broken into, so I found one. The attendant informed me that it was full, so I duly informed him in my broken Polish that my grandfather had fought at Monte Cassino. As an older person, he knew what this meant, and immediately found me a parking space. I expected Ludwik to be delighted by the story when I got back to Britain, but he sat impassively and barely reacted. This is the nearest I got to talking about Monte Cassino with him. Whether he was too traumatised, too modest, or just too sad, I do not know. All he passed on from that story of unsurpassed bravery is this picture of the ruins:

Ruins of Monte Cassino following the Allied Campaign

At least Italy was saved from a Communist takeover. However, Allied support for the Red Army had helped the USSR to sweep East ahead of the Allies and get to Berlin first. The result was that Stalin gained control of Eastern Europe by a combination of deceit and force.

Monte Cassino “de-mobilisation” Parade – 02 September 1945

The Polish II Corps stayed on in Italy until 1947, where Ludwik gained a Diploma in Telephony. While he was in Italy, my father had been growing up in Africa, and records kept by a Polish priest at Masindi indicate a problem with discipline, and a lack of male role models because “the fathers were all away in the army”.

The Road to Britain: New Lives Begin

Having fought bravely to get their country back, Polish servicemen found themselves without a home once the war had ended. Stalin’s surrogate governments branded them spies and traitors, subjecting those who tried to return to their families to show-trials for espionage, imprisonment and execution.

Once they were given the option by the British government, the overwhelming majority chose to start their lives again in Great Britain. The result was the first mass-immigration act passed in this country, the Polish Resettlement Act 1947.

Ludwik, Adela and Mieczysław were amongst the 160,000 Poles brought to Britain under this act. They were mostly housed in army camps and air force bases no longer needed after the war, described graphically on the wonderful website: “Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK 1946 -1969”.

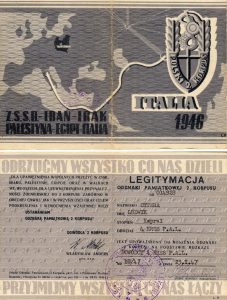

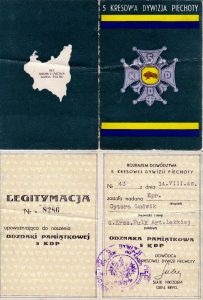

Insignia of 5th Kresowa Infantry Division

Ludwik was part of the 5KDP (5th Kresowa Infantry Division) which sailed direct from Italy to Glasgow. However, Ludwik took a different route: in common with his compatriots of the First Carpathian Brigade, of which he was a member before transfer to the 5KDP, he took the overland route through France. He must have arranged this because he wanted to visit Adela’s brother and his family. Ludwik in uniform:

Ludwik Cytera with the Gutewiez family in France 1945

Ludwik then sailed from France to Southampton in 1947 for resettlement. His first home in Britain was the Daglingworth Camp near Cirencester according to the list of regiments on the resettlement camp website and the Army Attestation that he signed on arrival.

The remains of Daglingworth Polish Resettlement Camp near Cirencester, today.

This was effectively Prime Minister Attlee’s two-year contract giving the Poles the right to live in Britain, in return for them accepting training and getting a job at the end of it.

General Wadislav Anders C.O. Polish II Corps with British Prime Minister Rt. Hon. Clement Atlee MP

The resettlement camps were only meant to last around two years. In them the former combat troops joined the Polish Resettlement Corps (PRC), where they were taught English and some trades to help them get jobs. But many camps continued right into the 1950’s and 60’s, with many Poles spending the rest of their lives in the camps and a whole generation of children growing up in them.

Eventually they were all consolidated down to one camp at Stover Park in Exeter, which then became a care home for elderly Polish ex-servicemen and their families and those who could not integrate into British society. It is now known as Ilford Park Polish Home and still looks after them to this day with MoD funding: something that should make every British citizen proud.

A New Life

Ludwik made no attempt to continue the Polish way of life in one of these communities. This was probably because he was lucky enough to get a job pretty quickly, before his son and wife had even come to join him from Africa. His pre-war job in a concrete factory must have given him the experience to get a job as a brick-maker, semi-skilled and relatively well-paid compared to the manual labour that most of his compatriots, knowing no English or having no contacts, had to do. His army records show that his first employer in Great Britain was the Cattybrook Brick company of Bristol, the nearest big city to Cirencester:

He remained part of the army after starting work, by means of a transfer to the army reserves based at Codford (near Salisbury) after leaving Daglingworth.

His son (my father) Mieczysław and Adela arrived in Southampton, on 8th March 1948 on the SS Carnarvon Castle. They probably passed through the Daglingworth Camp as a transit centre where they were re-united, as many were. Shortly afterwards they moved into Cattybrook Farm together, which my father remembered. Ludwik was finally discharged from the army on 28th May 1948.

With the totalitarian grip tightening on Poland and persecution rife, there was to be no going back to communist Poland now. Life in Great Britain had truly begun, and they were here to stay.

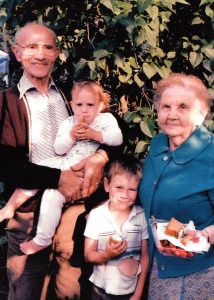

I brought Ludwik to see the flat I had bought in Redland,Bristol in 1990. It was a touching sight when he and Adela stood up to leave as they were still holding hands at their age. It was the last time I was to see them together as Adela went to a nursing home after I had left Great Britain for a job in France.

Luwik, Adela and the neighbours children in the 1990’s

In the mid 1990s I visited Ludwik in Bristol. He was living by himself by then and I still vividly remember the scene as he came out of the back door to meet me clutching a plastic bag. He knew his time was nearly up and he wanted me to have his war medals. All six of them, including the prestigious Monte Cassino Cross. He emphasised how important its contents were and clearly wanted me to do something with them. Though I cannot remember his exact words, they were something like “nauczyć się o tym” which means “learn about this”. He was not asking me for a favour, he was giving me an instruction. Only later did it become clear what it was.

Only in 2017 with my father’s passing did they see the light of day again, signalling me to tell the story as Ludwik had intended. The Medal Wojska is sometimes identified as the Polska Swemu Obroncy (Polish Defence Medal). According to the Śikorski Museum in London, this is incorrect. The error comes about because some combatants did not get their Medal Wojska due to post-1945 chaos and the de-recognition of the Polish Government in Exile (whose headquarters later became the Śikorski Museum). So the British Government issued the War Medal 1939-45 instead, and some combatants like Ludwik received both.

Luwik’s war medals from left: Krzyż Pamiątkowy Monte Cassino (Monte Cassino Commemorative Cross); Medal Wojska (Polish War Medal); the 1939-1945 Star; Italy Star; Defence Medal; War Medal 1939-45.

Below are the certificates for the British War Medal in Polish and the Polish War Medal signed by General Anders.

The Monte Cassino Commemorative Cross has a certificate called a “Legitymacja”. “Let us reject all that divides us, let us embrace all that unites us”.

Ludwik died in hospital in Bristol on 27th January 1997, and is buried at South Bristol Cemetery in the Polish plot. Here is his memorial which I had erected in 2014, many years after his death. The mention of Monte Cassino on his gravestone is the first time anyone had paid tribute to him, either in life or in death, since the award of his medals.

Christopher Cytera.

Edited from the comprehensive family history for AFHG by Ian Reed, November 2020.

©2017-2021

Excellent history of a little known chapter in the history of WWII and one which merits further research and publication. As Poland fell under tyranny of the Soviet Union its real history in WWII has been lost and worse manipulated to suit the post war narrative of the Soviet Union. Thankfully experiences are shedding a new light on these episodes which will lead to a greater understanding of the fate of Poland during WWII.

Thank you for sharing this.

My father was also at monte casino and never talked about it. My mother was at daglingworth camp. That’s where they met. When I finished your article and saw the photo of your grandparents I realised that I recognised them! Probably from the polish church and club in Bristol. Such a small world. And a cruel but also beautiful one as well. X

My father was also at Monte Cassino. My parents met in Dagingworth, my mother having survived Siberia and Masindi. It has taken me so long to research their stories properly as my father died young and my mother did not want to share much of her history, for obvious reasons. I am finally writing a book about her journey, and looking to fill the gaps from other sources. It is very reassuring that others of my generation are trying to know more about this very difficult part of history.

My dad also fought at Monte Cassino and was in Daglingworth Camp. He left Daglingworth in June 1946 to begin a life in Canada. I am left with his medals and many pictures and documents but very little stories about his time in the Army. He was in 15 Poznan Ulan Regiment and then transferred to 25 Pulk Ulanow Wielkopolskich.