Belgian Resistance – Fabrice Maerten, Belgian State Archives

A brief look at the complexities, contrasting methods and aims of Belgian resistance groups following the chaos of Nazi Occupation.

This article from www.belgiumwwii.be, is published by kind permission of “The Belgians Remember Them” memorial organisation (see end).

(Traduction en français à la fin de cette page)

THE KINGDOM OF BELGIUM – 1940/1945

German forces attacked Belgium on 10th May 1940 but despite a courageous defence by the small Belgian Army supported by British and French troops, the Wehrmacht out manoeuvred the Allies by its main attack through the Ardennes, and Belgium surrendered on 18th May.

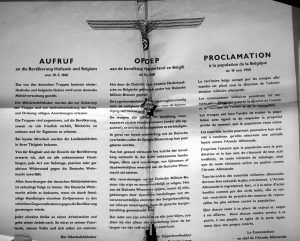

Pre printed German occupation proclamation, dated 10th May 1940

Like many countries invaded by the NAZI’s during World War Two, civilian responses were mixed, ranging from acceptance of their fate through to passive resistance and to direct action. Without the structure of national governments the focus was often blurred along previous political lines leading to disagreements regarding the direction of approach. In June 1941 the German invasion of the USSR and then the introduction of compulsory work in Germany in October 1942 helped better focus actions by the various resistance groups, but it was not always straightforward.

This brief look at Resistance in Belgium by Fabrice Maerten, member of the scientific team of the Belgian State Archives (CegeSoma), explains some of the complexities of the inter-political mix of forces during the Belgian Occupation.

1. The Front for Independence – “Le Front d’independance” (FI)

Born at the dawn of 1942, the Front for Independence (FI) numbered tens of thousands of members during 1943 and 1944, making it the most extensive resistance movement during most of the Occupation. But at the Liberation, the movement appeared as a colossus with feet of clay.

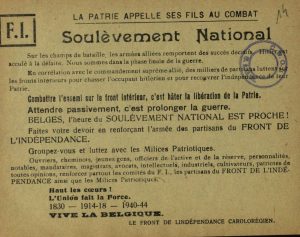

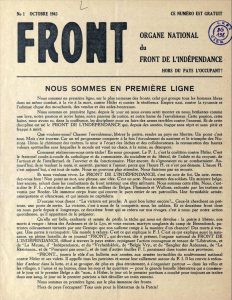

FI “National Uprising” leaflet of 1944

The myth of its creation and a slow start

The Front for Independence (FI) was not set up on 15 March 1941, as its main leader, journalist Fernand Demany, wrote after the war. In fact, it was created in several stages. In May 1941, the Communist Party of Belgium published a «Manifesto to the peoples of Flanders and Wallonia for the independence of the country“.

Writer & journalist Fernand Demany – Leader of the FI

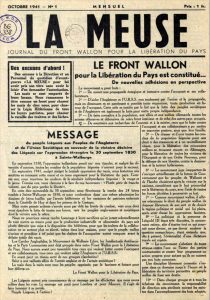

The attack on the USSR by Nazi Germany on 22 June 1941 enabled the Communists to seek dialogue with like-minded people. The new organisation thus created took the form of a “Walloon Front for the Liberation of the Country”, officially launched in the first issue of the underground newspaper “La Meuse” published in October 1941.

Newspaper «La Meuse” – October 1941 (cegeSoma)

The Walloon Front, which united Communists, Walloon militants, anti-fascist intellectuals, and “anglophiles”, served as a model for the FI which first appeared in certain regions in late autumn 1941 or early winter 1941-1942. But it was not until March 1942 that the group organized itself throughout the country and that the name «Front of Independence» (FI), emphasising the national character of the fight, was used everywhere.

Failure and success

The initial objective of the Communists, who began the FI and led it throughout the war, was to bring together all the existing groups in order to better coordinate action against the occupying forces and thus better cooperate in driving them out of the country. But this desire ran up against the mistrust of the Underground Socialist Party and right-wing groups, who refused to be part of an organization set up by communists. Therefore, apart from those linked or close to the Belgian Communist Party and the small band of free thinkers often from the liberal family, membership was on an individual basis.

In 1942 FI recruitment announcements disseminated by small underground newspapers and leaflet campaigns, as well as in conversations and posters, initially attracted very little response outside the circles of those originally involved. International developments and especially the introduction of compulsory work in Germany (Service du Travail Obligatoire – STO) from October 1942, changed this situation. In particular, the involvement of the FI in the fight against deportation by the creation of committees to help those who refused to join STO from the spring of 1943, allowed it to gradually expand within large sections of the population.

Essentially an unarmed popular movement

Although the FI advocated direct action against the Occupying Forces, and had as its final objective a national uprising, it portrayed itself above all as a propaganda and humanitarian resistance movement. So, in 1943 and 1944, thousands of members were mobilized to write, produce and distribute some 150 underground hand-outs directly or indirectly linked to the FI.

They were also responsible for spreading leaflets and decorating towns and villages with the colours of the national flag on symbolic dates.

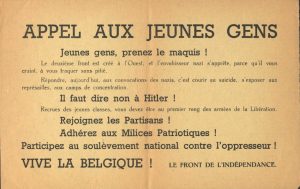

Front de l’Indépendance leaflet

In addition, the organization helped not only the rebels, but also the families of political prisoners, (via Solidarity), as well as hunted Jews, (via the Defence Committee of Jews); resistance fighters in hiding; French prisoners and Russian & Polish escapees. Moreover, it supported the patriotic and social struggle in companies via the Trade Union Struggle Committees (CLS) which published instructions through a hundred underground newspapers and numerous leaflets which initiated work stoppages and sabotaged production destined for Germany.

Hostile direct action was carried out during most of the Occupation by Belgian Partisans who, whilst being affiliated to the FI, acted semi-independently of the movement as the armed wing of the Communist Party.

2. The Patriotic Militia.

In the Spring of 1944 the communist leaders at the head of the Front for Independence (FI) created the “Patriotic Militia” (Milices Patriotiques – MP), to work directly towards the liberation of Belgium. It was designed to combine the majority of resistance fighters with other sections of the population wishing to fight the Occupying Forces, but the idea did not have the expected results. Many resistance fighters refused to throw themselves into the fray. In addition, movements like the Secret Army had better assets in terms of equipment and supervision. Ultimately, most Patriotic Militia (MP) members were individuals who had previously taken part in FI non-violent forms of activity. The lack of means and men with London urging prudence and the eventual rapid liberation of the country limited the involvement of the Milices Patriotiques (MP) in the armed struggle, and deprived the Communist Party of a very valuable source of influence when the country was eventually returned to the Belgian authorities.

A vain initiative

In January 1944, the FI had released a plan in which Liberation Committees, formed under its initiative, would assume certain powers for maintaining law and order in the context of a national uprising supported by a general insurrection. However, the hostility of the Belgian Government in London forced the FI to abandon this project and the small impact of the FI on the eventual liberation of the country prevented the FI’s organization from playing an important political role in September 1944. Nevertheless, to show its gratitude to the movement, the Government of Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot, when back in Belgium, included Ferdnand Demany in its organisation.

Newspaper «Front» N° 1 edition of October 1943 (CegeSoma)

3. The Armed Partisans

On 22nd June 1941, Germany’s invasion of the USSR lead the Communist International based in Moscow, to issue an order on June 30, that all parties must use every means possible to disrupt enemy activity in their area in a bid to relieve the Red Army.

Initially the Communist Party of Belgium (PCB) had difficulty in implementing this directive because it was contrary to communist working class tradition in Belgium and to the accepted Marxist theory. The move to action was thus much slower and the recruitment of sufficient numbers was made even more difficult because public opinion was not in favour of violence, because from the outset, the occupying Wehrmacht forces exerted overwhelming repression against the first small band of Belgian partisans.

Therefore, from August 1941, the PCB called on former Spanish Republican war veterans, (directly linked to the Communist International) and intellectuals to run the active resistance cells.

Due to the lack of men, means and experience, actions carried out before the spring of 1942 were sporadic and generally had little impact.

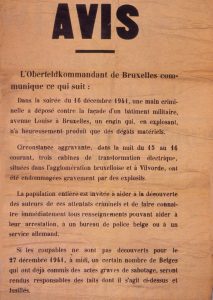

Translation: “The Military Governor (of Belgium) communicates the following. On the evening of 14 December 1941, criminals placed a device against the facade of a military building, which fortunately produced only material damage. Further aggravating circumstances took place during the night of 15 and 16 December, when three electrical transformer cabins in the Brussels area and in Vilvoorde were seriously damaged by explosives. The entire population is invited to help in the search for the perpetrators of these criminal attacks and to inform the Belgian Police or any German service. If the culprits are not found by noon on 27 December 1941, a number of Belgians who have already committed serious acts of sabotage, will be made responsible for the above-mentioned acts and shot”.

The first wave of attacks

In March 1942, those whom the PCB then referred as the “Belgian Partisans” began executing collaborators, and in particular Rex Party mayors and leaders. This was still little noticed by the majority of the population even though the organization now included communist militants from the working classes within the big cities and industrial centres of Wallonia.

The “Rexists” were members of the pro German Rex Party, a political party of the extreme right-wing which collaborated with the Nazis. The Rex Party leader led the “Wallonia Legion” to fight with the Nazis on the Eastern Front and was sentenced to death in absentia after the war, but took refuge in Spain to escape justice.

Around 850 collaborators were killed during the Occupation by various resistance groups.

However, these groups, which stepped up attacks from the summer of 1942, were now supported by the Front de l’indépendance (FI). While retaining their autonomy, there were too weak to withstand German police investigations for any length of time.

In Brussels, the action was led, in particular, by young Communist Jews who began to attack Germans from the end of 1942. The resulting severe retribution of the Germans was such that the survivors quickly abandoned direct attacks on the Occupying Forces in favour of focusing on executing Belgian collaborators and sabotaging the German war machine.

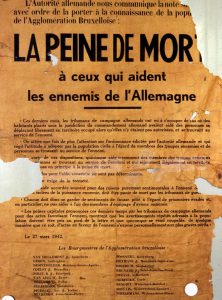

Nazi retribution was swift and merciless over 1000 resistants were executed during the Occupation

In the summer of 1943, a wave of arrests among the ranks of the PCB, which had started a few months earlier, overwhelmed the Party and the Partisans who were still closely linked to it. The blow to the armed wing of the PCB lead to a sharp decrease in its activities for the first time since its creation. However the slowdown was only short-lived and as early as the autumn of 1943, the Partisans carried out attacks and sabotage, especially on the railways, at a rate never before attained.

As a result, from this time on, recruitment took place outside Communist hot-beds. In fact, the movement now attracted non-politicized young people affected by the constant deterioration of living conditions and those directly threatened by the imposition of compulsory work in Germany. They were convinced of the final success of the Allies and admired Red Army successes.

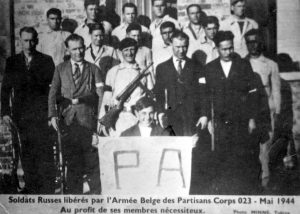

Soviet Russians fought with the communist inspired Armed Partisans (Partisans Armés)

However, apart from Limburg and Flemish Brabant, membership was still mainly based in Brussels and in the Walloon industrial areas, where the Communists established their organization and where the Socialists, by their wait-and-see attitude, left a void.

A bomb attack on Rex’s premises on Rue de Laeken in Brussels on 1 October 1941, resulted in the death of a rexist. This isolated attack foreshadowed the series of bloody attacks perpetrated mainly by the PA (Partisans), which increased from 1942. (CegeSoma)

Terror and counter terror

Following the Allied landings on the beaches of Normandy in 1944, acts of sabotage were stepped up. Moreover, in several regions of the country, there became a mini civil war between the Resistance, and in particular the Partisans now called “Armed Partisans”, on the one hand, and the armed collaborationist groups, incensed by the ever increasing number of their members killed at that time by the Resistance.

Sabotage of transport links were a major factor in supporting the Allied advance

The increased repression carried out by the German occupying forces and collaborators could no longer manage to stem the flow of actions led by constantly renewed teams of Partisans.

After Liberation

British 21st Army Group and US troops arrived in Belgium on 2 September 1944 and in the next few days captured 25,000 Germans while 3,500 Germans were killed. Within ten days Belgium was free. Photo: British troops enter Brussels on 4th September 1944.

In spite of an increasing membership during the last year of the Occupation, the Armed Partisans (Partisans Armés – PA), re-named again on the eve of the Liberation as the «Belgian Army of Partisans», never really constituted a mass movement.

13,246 individuals were recognized as members after the War. But there had been intense repression by the Occupying and Collaborationist Forces suffered by all resistants. In Hainault for example, one Partisan in two was arrested and one in five died. The effect of this plus those communist militants not active in the armed struggle, meant there were probably only a few thousand Partisans actively engaged at the time of Liberation. Since they were poorly armed, their role, essentially, supplemented the numbers of Allied infantry troops in those areas where numbers of Partisans were relatively high, to act as prison warders of alleged collaborators.

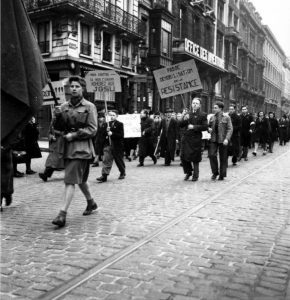

Following the battles which resulted in Belgium’s liberation, the Belgian Communist Party (PCB) intended to use the Armed Partisans as a means of exerting forceful pressure upon the government. The PCB’s appeal to them to march on Brussels on 28 November 1944 to help bring down Hubert Pierlot’s conservative government ended in great disappointment for the Communists.

28th November 1944 – PCB march on Brussels in a half hearted bid to alter Belgian politics.

Few men answered the call and those who did respond were easily pushed back by the Belgian Gendarmes. The communist PCB failed to understand that most of its elite troops fought only to drive the Occupying Forces out of the country and not to further a political purpose. The resistants turned away from the organisation when it supported political demands and from then on, it was very quickly confined to a marginal role in post-war society. Only the CLS (Comités de lutte syndicale), which had become a single trade union, carried any weight in the Belgian social landscape. But this communist trade union base quickly dissolved into the General Federation of Labour in Belgium (FGTB), created in April 1945 and dominated by the socialists.

END

Permission to use this article from www.belgiumwwii.be , was kindly provided by Wilfred Burie, President, Belgium Remembers Them.

The informative website at: www.belgians-remember-them.eu is highly recommended and gives full details of all crashes involving Royal Air Force aircraft in Belgium during WWII, including location, crews, casualties, missing in action, survivors & PoW’s.

Belgians Remember Them – a tribute to RAF airmen who fell in Belgium and the Resistance involved in their rescue. The annual ceremony at the Rebecq Memorial, Walloon Brabant. HM the King represented. Details & applications: belgian.remember@gmail.com

Wednesday, 29 September 2021, 10 a.m.

(Traduction en français)

1. La Front de l’indépendance

Né à l’aube de l’année 1942, le Front de l’indépendance rassemble plusieurs dizaines de milliers de membres en 1943 et 1944, ce qui en fait le mouvement de résistance le plus étoffé pendant la majeure partie de l’Occupation. Mais à la Libération, le mouvement apparaît comme un colosse aux pieds d’argile.

Le mythe de la fondation, un lent démarrage

Le Front de l’indépendance (FI) n’a pas été fondé le 15 mars 1941, comme l’a écrit après-guerre son principal dirigeant, le journaliste Fernand Demany. En réalité, sa création s’effectue en plusieurs étapes. En mai 1941, le Parti communiste de Belgique publie un « Manifeste aux Peuples de Flandre et de Wallonie pour l’indépendance du pays ». L’attaque de l’URSS par l’Allemagne nazie le 22 juin 1941 permet aux communistes de trouver des interlocuteurs. La nouvelle structure en construction prend d’abord la forme d’un Front wallon pour la libération du pays, lancé officiellement dans le premier numéro du journal clandestin liégeois La Meuse paru en octobre 1941. Le Front wallon, qui unit des communistes, des militants wallons, des intellectuels antifascistes et des « anglophiles », sert de modèle au FI qui prend naissance dans certaines régions à la fin de l’automne 1941 ou au début de l’hiver 1941-1942. Mais il faut attendre mars 1942 pour que l’organisation s’organise dans l’ensemble du pays et impose partout l’appellation « Front de l’indépendance », appuyant le caractère national du combat.

Un échec et une grande réussite

L’objectif initial des communistes, qui sont à l’origine du FI et le dirigent pendant toute la guerre, est de créer par ce biais une coupole qui rassemble l’ensemble des groupements existants pour mieux coordonner l’action contre l’occupant et mieux contribuer à le chasser du pays. Mais cette volonté se heurte à la méfiance du Parti socialiste clandestin et des groupements de droite, qui refusent d’intégrer une organisation mise sur pied par des communistes. Dès lors, en dehors des cercles liés au PCB ou proches de ce dernier et de noyaux de libres penseurs issus souvent de la famille libérale, les adhésions s’effectuent de manière individuelle. Au départ, en 1942, le discours volontariste du FI transmis par de petits journaux clandestins et lors de campagnes de tracts, de chaulage et d’affichage ne séduit guère en dehors du milieu d’origine du mouvement. L’évolution de la situation internationale et surtout la mise en place du travail obligatoire en Allemagne à partir d’octobre 1942 changent la donne. En particulier, l’implication du FI dans la lutte contre la déportation par la création de comités d’aide aux réfractaires au travail obligatoire à partir du printemps 1943 lui permet de s’étendre peu à peu dans de larges couches de la population.

Un mouvement populaire essentiellement non armé

Si le FI prône l’action directe contre l’occupant et a pour objectif final le soulèvement national, il se manifeste surtout comme un mouvement de propagande et de résistance humanitaire. Ainsi, en 1943 et 1944, des milliers de membres sont mobilisés pour rédiger, confectionner et/ou distribuer les quelque 150 feuilles clandestines en rapport direct ou indirect avec le FI. Ils sont également chargés de répandre des tracts et de pavoiser les villes et villages aux couleurs du drapeau national lors de dates symboliques. En outre, l’organisation vient en aide non seulement aux réfractaires, mais aussi aux familles des prisonniers politiques via Solidarité du FI, aux Juifs pourchassés par le biais du Comité de défense des Juifs, aux résistants dans la clandestinité, aux prisonniers français, russes et polonais évadés. Par ailleurs, elle soutient le combat patriotique et social dans les entreprises, via les Comités de lutte syndicale (CLS) qui diffusent des mots d’ordre par le biais d’une centaine de journaux clandestins et de très nombreux tracts, provoquent des arrêts de travail et sabotent la production destinée à l’Allemagne.

L’action directe est menée pendant la majeure partie de l’Occupation par les Partisans (belges), qui tout en étant affiliés au FI, agissent de manière quasi indépendante du mouvement en tant que bras armé du Parti communiste.

2. Milices Patriotiques

Pour œuvrer à la libération du pays, les dirigeants communistes à la tête du FI créent au printemps 1944 les Milices patriotiques (MP), censées rassembler la masse des réfractaires et les autres éléments de la population désireux d’en découdre avec l’occupant. Mais l’opération n’aboutit pas aux résultats escomptés : de nombreux réfractaires refusent de se jeter dans la mêlée ; ensuite, des mouvements comme l’Armée secrète disposent de meilleurs atouts en termes de matériel et d’encadrement. En définitive, la plupart des membres des MP sont des personnes ayant œuvré précédemment dans les formes d’activité non violentes du FI. Le manque de moyens et d’hommes, les consignes de prudence de Londres et la libération rapide du pays limitent d’ailleurs l’implication des MP dans le combat armé et privent le Parti communiste d’un argument de poids à l’heure de la reprise en mains du pays par les autorités belges.

Une vaine instrumentalisation

En janvier 1944, le FI rend public un plan dans lequel les Comités de libération formés à son initiative assumeraient certains pouvoirs en termes de maintien de l’ordre dans le cadre d’un soulèvement national appuyé par une grève générale insurrectionnelle. Mais l’hostilité du gouvernement belge de Londres qui contraint le FI à abandonner ce projet et le peu d’impact du FI sur la libération du pays ne permettent pas à l’organisation frontiste de jouer un rôle politique important en septembre 1944. Néanmoins, pour manifester sa reconnaissance vis-vis-vis du mouvement, le gouvernement d’Hubert Pierlot, de retour au pays à la Libération, intègre Fernand Demany dans son équipe.

Et le Parti communiste, qui est toujours aux commandes du FI, espère lui faire remplir le rôle de pilier qu’il n’a jamais pu construire dans la société. L’échec de l’instrumentalisation du FI lors de la tentative du Parti pour faire tomber le gouvernement en novembre 1944 montre à quel point il s’est lourdement trompé. La plupart des adhérents au FI ont rejoint le mouvement pour aider à chasser l’occupant du pays sans aucune arrière-pensée idéologique. Ils se détournent donc de l’organisation lorsque celle-ci appuie des revendications politiques. Dès lors, ils la confinent très rapidement à un rôle marginal dans la société d’après-guerre. Seuls les CLS, devenus Syndicats uniques, pèsent alors d’un certain poids dans le paysage sociétal belge. Mais cette base syndicale communiste se dissoudra rapidement dans la Fédération générale du travail de Belgique (FGTB), créée en avril 1945 et dominée par les socialistes.

3. Les Partisans armés

L’invasion de l’URSS par l’Allemagne le 22 juin 1941 conduit le 30 juin l’Internationale Communiste, qui dirige alors depuis Moscou tous les partis communistes, à ordonner à ces derniers de désorganiser par tous les moyens l’arrière-pays de l’ennemi pour soulager l’Armée rouge. Cette injonction est difficile à mettre en œuvre par le Parti communiste de Belgique (PCB), car elle est contraire à la tradition ouvrière et communiste dans le pays ainsi qu’à la théorie marxiste enseignée. Le passage à l’action est d’autant plus lent et le recrutement adéquat d’autant plus difficile que l’opinion publique n’est alors pas favorable à la violence et que l’occupant exerce dès le départ une répression implacable contre les premiers noyaux de partisans. Pour diriger ces cellules actives à partir d’août 1941, le PCB fait appel à des anciens de la guerre d’Espagne, à des militants liés directement à l’Internationale Communiste et à des intellectuels. Par manque d’hommes, de moyens et d’expérience, les actions menées jusqu’au printemps 1942 sont sporadiques et généralement de peu d’ampleur.

La première vague d’attentats

En mars 1942, ceux que le PCB appelle désormais dans sa presse les Partisans belges commencent l’exécution de collaborateurs, et en particulier de bourgmestres rexistes. Toujours peu appréciée par la majorité de la population, l’organisation peut désormais compter sur l’adhésion, dans les grandes villes et les bassins industriels wallons, de militants communistes issus du monde ouvrier. Mais ces groupes, qui multiplient les attentats à partir de l’été 1942 et sont désormais soutenus par le Front de l’indépendance tout en gardant leur autonomie à son égard, sont trop ténus pour résister longtemps aux investigations des polices allemandes. À Bruxelles, l’action est en particulier menée par de jeunes Juifs communistes qui s’attaquent à partir de la fin 1942 à des Allemands. La répression subie est telle que les survivants renoncent rapidement à s’attaquer directement à l’occupant pour se focaliser sur l’exécution de collaborateurs belges et sur le sabotage de la machine de guerre allemande.

Un coup d’arrêt et la montée en puissance

À l’été 1943, une vague d’arrestations entamée quelques mois plus tôt dans les rangs du PCB submerge le Parti et les Partisans qui lui sont toujours intimement liés. Le coup porté au bras armé du PCB entraîne pour la première fois depuis sa création une nette diminution de ses activités. Mais le ralentissement n’est que de courte durée. Dès l’automne 1943, les Partisans enchaînent les attentats et les sabotages surtout ferroviaires à un rythme jusqu’alors jamais atteint. C’est qu’à partir de cette époque, le recrutement s’effectue bien au-delà du creuset communiste. En effet, le mouvement attire désormais des jeunes non politisés touchés par la détérioration constante des conditions de vie, menacés directement par l’imposition du travail obligatoire en Allemagne, convaincus du succès final des Alliés et admiratifs devant les succès de l’Armée rouge. Ceci dit, en dehors du Limbourg et du Brabant flamand, les adhésions s’opèrent surtout à Bruxelles et dans les bassins industriels wallons, là où les communistes ont réussi à implanter l’organisation et où les socialistes ont, par leur attentisme, laissé un grand vide.

Terreur et contre-terreur

Après le débarquement allié sur les plages de Normandie, les sabotages se multiplient. Par ailleurs, on assiste dans plusieurs régions du pays à une véritable mini-guerre civile entre d’une part les résistants, et en particulier les Partisans désormais appelés Partisans armés, et d’autre part, les groupes armés issus de la collaboration, furieux du nombre toujours plus élevé des leurs abattus alors par la Résistance. La répression accrue orchestrée par l’occupant et les collaborateurs ne parvient en effet plus à ce moment à endiguer le flot d’actions menées par des équipes sans cesse renouvelées de Partisans.

En retrait à la Libération

Malgré ces multiples adhésions de la dernière année d’occupation, les Partisans armés, dénommés à la veille de la Libération “Armée belge des partisans”, ne constitueront jamais un mouvement de masse. 13.246 individus sont reconnus à ce titre après la guerre, mais vu l’intense répression subie (dans le Hainaut par exemple, un Partisan sur deux est arrêté et un sur cinq décède) et la reconnaissance par ce biais de militants communistes non actifs dans la lutte armée, ils ne sont sans doute que quelques milliers à être à pied d’œuvre au moment de la Libération. Et comme ils sont pauvrement armés, il serviront alors essentiellement d’infanterie d’appoint aux troupes alliées dans les zones où ils sont relativement bien représentés et de garde-chiourmes des collaborateurs présumés emprisonnés.

Après les combats libérateurs, le PCB compte notamment avoir recours aux Partisans armés comme moyen de pression « musclé » vis-à-vis du gouvernement. Mais l’appel que le Parti leur lance à marcher sur Bruxelles le 28 novembre 1944 pour contribuer à faire tomber le gouvernement conservateur d’Hubert Pierlot se solde pour les communistes par une terrible déconvenue. Peu d’hommes se mobilisent et ceux qui obtempèrent à la demande se laissent facilement refouler par les gendarmes. Le PCB n’a pas compris que la plupart des membres de ses troupes d’élite ne se sont pas battus dans un but politique, mais uniquement pour chasser l’occupant du pays.

par Fabrice Maerten, CegeSoma

FIN

L’autorisation d’utiliser cet article, publié sur a www.belgiumwwii.be, été aimablement fournie par M.Wilfred Burie, Président de “Belgium Remembers Them” – www.belgians-remember-them.eu