Ab Homburg: Dutch SOE Agent & Spitfire Pilot – Anke ter Doest

The remarkable story of a Dutch resistance fighter who escaped to England twice and became a RAF fighter pilot .

In total darkness two young men in a rowing boat paddled frantically in the direction of England, the third passenger sat at the front on the look-out for possible danger. It was a moonless Saturday night on March 22nd 1941. In the harbour of IJmuiden only its two lighthouses, in darkness thanks to the blackout, were silent witnesses of the escape. After a last pint in their local pub to steady their nerves Ab Homburg and his two friends Cor Sporre and Willem de Waard made a plunge for freedom. Their rowing boat was ‘borrowed’ from Cor’s employer, the steel factory Hoogovens in IJmuiden. Although it was powered with a small engine, they couldn’t start it before they were well out of earshot from the coast. It was a very bold move but they had prepared their plan a long time in advance.

Ab Homburg (i) Cor Sporre Willem de Waard

When Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10th 1940 Ab was nearly 23 years old, serving as a warrant officer in the army with the Motor Transport Corps. After the bombing of Rotterdam, on the fourth day following the German invasion, the Netherlands capitulated. The royal family and the government had already relocated to England by then. All troops were demobilised. At home now with his family in Velsen near the harbour town of IJmuiden, where his father ran a grocery shop, Ab was figuring out what to do with himself. He found a job as a technical supervisor in the garage of the Air Raid Protection in Velsen.

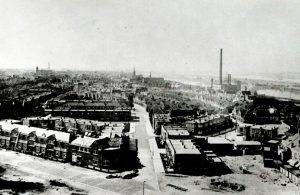

The medieval centre of Rotterdam, obliterated by German aerial bombing – 14th May 1940

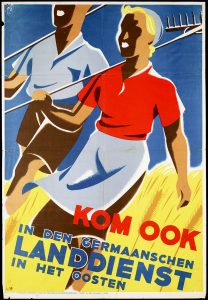

Although in the beginning of the occupation the Nazi’s put up a relatively lenient front, they took a firm grip on social and economic life. All fuel as well as a large portion of the food supply were confiscated for German use. Factories were forced to produce for Germany. German police patrolled and controlled the streets. Carrying an identity card became mandatory, Jews had the letter J stamped in theirs. Telephone communications, radio, newspapers and news bulletins in cinemas were placed under German control with the media showing Nazi propaganda. Prior to imposing forced labour Dutch citizens were urged to work in the ‘east’, meaning Germany, to relieve the increasing shortage of the labour force over there.

A picture of a well oiled, German run society where light skinned, blonde people energetically marched to work, cheerfully singing, was meant to win over reluctant souls.

Poster to promote work in Germany with the text: “Come and join the Germanic country service in the east” (vii)

National Socialist ideology did find a growing support indeed among Nazi sympathisers, who were organised in the Nationaal Socialistische Bond. Yet, resistance groups, inspired by the combative speeches of Queen Wilhelmina on the BBC over the clandestine Dutch sender Radio Oranje (Radio Orange) also gained momentum.

Queen Wilhelmina, the Netherlands longest serving monarch and the spirit of Dutch Resistance regularly broadcast from the BBC in London to her occupied country throughout the War.

After mounting tension between Jewish groups and militant Nazi collaborators the resistance became wide spread when the situation suddenly turned a lot more grim. On February 22nd-23rd 1941 the Nazis lifted around four hundred Jews from the streets in Amsterdam and loaded them onto lorries for transport to concentration camps. Outrage at these raids – or razzias – caused a protest strike in solidarity with the Jews, which later spread to other towns such as Zaanstad (not far from Velsen), Hilversum and Utrecht. In turn Nazi oppression increased. Instigators were executed and the resistance movement was forced even further underground.

Anti-Jewish raid in Amsterdam, 22-23 February 1941 (vii).

Ab had also joined the resistance by starting a vigilante group, de Knokploeg (the Thugs). But, when it became clear that the war would last a lot longer than expected he decided to join the war effort in England rather than support the resistance at home. Although the borders were locked, without a special German pass, the beaches were not (yet) cordoned off. Ships and fishing boats could still operate, albeit with a special licence.

Velsen, North Holland, Netherlands – the neighbourhood where Ab lived with his family. (vi)

Together with Cor Sporre , his army buddy who worked as a mechanic at Hoogovens steel factory in IJmuiden, he devised a plan. They had their eye on one of the factory’s rowing boats which they planned to convert into a motorboat with a purchased second hand engine. A childhood friend of Ab, Willem de Waard, was also invited on board the escape plan. Since none of them had any sailing experience they turned to a local skipper who, in spite of having serious doubts about their big plans with the tiny boat, gave them instructions on the use of a compass and on navigating the currents of the North Sea. The escape was to take place on a Saturday night because they were hoping the sudden absence of the boat would be less conspicuous during the weekend. No moon and calm weather were additional conditions.

On the day of their departure the bonus of a drizzly rain helped in keeping unwanted attention at bay so the three friends could go about their business unnoticed. That is almost unnoticed. Before jumping into the rowing boat, which was moored in the outer harbour, the hidden outboard engine, fuel, food and life jackets had to be retrieved from several of the factory’s outbuildings. At that moment a voice called out. Someone wanted a ride to freedom. No chance of that. Never sure who to trust, they were not going to risk having their plan spoiled at the last moment and the space was cramped enough with the three of them plus all their gear.

IJmuiden outer harbour showing Forteiland (Fort Island). (vi)

Now, having quietly passed the German checkpoint on a little island called Forteiland, in the outer harbour, came the moment of truth. Ab had previously tested the engine in a rain barrel but would it also be happy to burst into life at sea, and keep purring, in less ideal conditions? The little engine roared at start up and they could relax a little while. But not for long because suddenly a patrolling German Schnellboot cast its searchlights in their direction. They quickly turned their engine off as the boat sped towards them but, to their relief, it turned away again.

8th Flotilla German Kriegsmarine fast motor torpedo boats, (Schnellboot), were based at IJmuiden.

The rest of their journey was mostly hampered by ferocious sea sickness and when they were not throwing up they were scooping out litres of seawater with their briefcases. Finally, early Monday morning, after one and a half days at sea, the three exhausted men were picked up by a British warship, HMS Leda, off the coast of England and brought ashore at Harwich. With meticulous planning, plenty of courage and a dose of luck the perilous journey had a good ending.

H.M.S Leda, Halcyon-class Minesweeper – 1941

In London the three friends were interrogated by MI5 at the Royal Victoria Patriotic School, Britain’s ‘front door’ for refugees. This interrogation was not only common procedure for Engelandvaarders, which is the Dutch name for their expatriates escaping to England to join the allied forces, but for immigrants of all nationalities. During the interview their entire lives were subjected to scrutiny to test their reliability as genuine refugees instead of being spies working for the Germans.

MI5 – Royal Victoria Patriotic School, Trinity Road, Wandsworth, London SW18. (ii)

After their release by MI5 the trio split up to join the war effort. Willem de Waard joined No.10 Interallied Commando, consisting largely of non-British personnel from German-occupied Europe. Ab Homburg and Cor Sporre entered the arena of the secret services which would turn out to be a war zone itself, at least as far as the Dutch section was concerned.

Willem de Waard joined No.10 Interallied Commando (v).

Willem de Waard joined No.10 Interallied Commando (v).

The British and the Dutch intelligence services (SIS and CID) each employed their own undercover agents to gather information in the Netherlands and support the Dutch resistance. A new kid on the block was Special Operations Executive (SOE) which specialised in the dirty work of sabotage in the occupied countries ‘to set Europe ablaze’, as their founder, Prime Minister Churchill, put it. SOE were not yet operating in the Netherlands but were looking to set up their own Dutch (N) section. Rather than exchanging information and agents the services safeguarded their own territory due to a lack of trust and rivalry between themselves. In the process many agents would loose their lives in, what became known as, the Englandspiel (the England game).

Ab and Cor were the first Dutch secret agents recruited by SOE. Before weapons and ammunition could be distributed in the Netherlands SOE-N Section had to carry out groundwork in the form of setting up a network of contacts.

SOE Establishment – STS31 – Secret Training School, The Rings, Beaulieu, Hampshire (ii)

The first week of their training, starting at the beginning of April at Beaulieu, was indeed dedicated to techniques of recruiting and handling agents, a domain which was called “Political Warfare”. This first course also included a taster of railway sabotage which must have gone down well, especially after the initial disappointment of the two mechanics with the amount of theoretical instructions and the lack of practical exercises during this week.

However, the majority of their ten week intensive training program, which was continued at Winterfold House near Cranleigh and later Arisaig House in the Scottish Highlands involved practical as well as heavy stuff in the realm of subversive warfare. From now on their days were filled with Physical Training, Fieldcraft, Weapons, Explosives, Close Combat and Irregular Warfare such as demolitions. There was also Map Reading, undoubtedly an indispensable skill to be able to locate their position in the middle of nowhere and without street signs to go by. Driving various vehicles (a bicycle was one of them!) and Radio Transmission were also on the training menu. Although this last subject was a normal part of the program it makes little sense regarding the fact that they were sent without a radio transmitter. To receive further instructions from headquarters in England the two were supposed to rely on radios of friends where they could listen to a clandestine sender. There was no need for the usual lessons in parachute jumping yet because they would be dropped off by boat.

STS 4, Winterfold House, Cranleigh, Surrey (ii)

STS 21 Arisaig House, Inverness

Overall, the instructors were happy with the performance of their two Dutch students although in the beginning there were some concerns about their discipline which didn’t quite meet the English standards, at least not when it came to dress code. Still, an observation which kept cropping up was Ab’s tendency to be ‘supercilious’ and ‘self-opinionated’ and he was also noted for his preference to work alone. Nevertheless, Ab’s commitment grew as the teaching became more in depth within the last phase.

For their mission they needed a fake identity. To have their identity papers forged, a pair of glasses and new clothes made, they had to travel to London. Perhaps it was during one of these trips that Ab met his future wife Pamela Boreham? A romantic occasion which took place in May in the London Underground. As an aspiring undercover agent he couldn’t have picked a more suitable location.

At the end of June, after a short courtship and an almost equally short but intensive training – sufficient time was an unaffordable luxury – Ab was sent on his first assignment together with Cor. However, the boat dropping at the Dutch coast failed and the boat returned to England with the two agents still on board. A next attempt to land the team was going to be from the sky so now parachute training must have had to be arranged at the parachute school RAF Ringway near Manchester, although this is not mentioned in their training reports.

Learning how to roll upon landing and live parachute training from Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers – Secret Training School 51, RAF Ringway, Manchester (ii)

Finally the big event, called “Operation Glasshouse (A)”, began on the moonlit night of 9th September 1941, and this time they landed successfully on home turf not far from Utrecht. Being the first SOE agents the drop was complicated by the absence of a ‘reception committee‘ on the ground to guide them in and to explain where exactly they were.

After the jump Cor left his parachute behind in a ditch instead of burying it the way they were instructed. So much for discipline as far as security was concerned. He wanted to split up immediately so although he saw Ab looking for him, probably to make sure his friend was okay, he vanished straightaway.

The newfangled agents set out on their first mission dressed in their disguise. Ab was sporting a rather fake looking moustache, a beret, round spectacles and handmade clothes that were meant not to shout ‘Made in England’ and Cor was probably wearing a similar outfit. The SOE tailors only knew one design so, really, he could hardly be blamed for not wanting them to be seen together.

After a fruitless search for Cor, Ab made his way to his first contact, pastor Kruvelder in Utrecht. The cleric undoubtedly treated him to a hearty breakfast but the main purpose of his visit was to pass on a letter from SOE Headquarters for the Archbishop. Meanwhile, Cor first paid a surprise visit to his family in Haarlem, north of Amsterdam, who were very surprised indeed as they had been informed by Ab’s brother-in-law of their escape to England. Once they got over the shock Cor found his dear uncle and aunt prepared to have their cigar shop used as a contact address by future agents and the shop would prove to be a very useful location in times ahead. His uncle’s radio, hidden in a cupboard underneath the staircase, would serve to receive coded information about a pre-arranged pick up by boat from the beach, their mission fulfilled or not.

Ab in the meantime started recruiting agents, with mixed results. Their contacts, in Rotterdam and The Hague, supplied by SOE, turned out to have lost their appetite to ‘play’ after some bad experiences or were never interested to play in the first place.

Another contact was wasted due to a clumsy advance. The approach of a contact is a delicate matter to be carried out with the utmost care, a technique they had learned in their training, but not everybody had a knack for it. Cor blew it by addressing the person too directly. After this last fiasco in the recruitment department they had to rely on their own resources to find new candidate agents. But then, about two weeks after their dropping, the awaited pick-up call came through over the radio. The two men hurried to the given location on the beach at Noordwijk to be collected by a motor torpedo boat.

The beach at Noordwijk, South Holland

They set up their signal lamps in the sea and hid in the dunes, hoping the lamps would not be detected by German curfew patrols. Numb from the cold they waited and waited but to no avail even though they could hear the boat coming. Their lamps were not noticed by the Germans nor by the English torpedo boat. When renewed attempts also didn’t work out one thing became clear: the pick-up missions from the flat Dutch beaches turned out to be extremely complicated, even more so than the droppings. The agents had to make their own arrangements to get back to England, as the crackling and sizzling radio’s secret sender de Flitspuit (the Flyspray) now informed them.

While investigating alternative return possibilities a next complication loomed on the horizon. Ab was troubled by a toothache which needed attention. Aware of the risk involved in seeing his regular dentist Ab turned to a former army buddy, Jan Jacob Vos, who ran a dental practice in Amsterdam. What he didn’t know was that his friend had become a Nazi collaborator and now lived up to his name: Fox, which is Vos in Dutch. The dentist, who already knew that Ab had escaped from Holland, laid a trap. He said he was working against the Germans so Ab felt confident enough to ask his friend to do him some favours for the greater good. The crafty “fox” was quick to promise his cooperation in becoming part of Ab’s network.

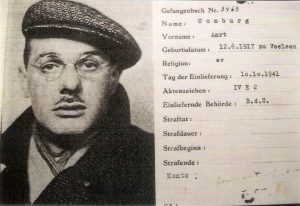

German prison registration card for Ab Homburg – 1941. (i)

Straight after his second dental visit on October 8th Ab was stopped by a car not far from the practice. Two members of the Dutch Detective Police (Rijks Recherche) jumped out with their pistols drawn. After a first questioning at the office of the Dutch Gestapo, they took him next day to the office of the Sicherheits Polizei (Nazi security police) where he was subjected to further, and this time also heavy handed, interrogations which Ab underwent bravely. When it was clear that the Sicherheits Polizei knew all about his escape to England – the Germans even produced Cor’s parachute – he only confessed to his real name, Ab Homburg.

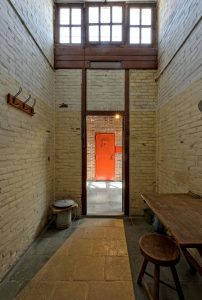

He was then detained at the prison, nicknamed Oranjehotel (Orange Hotel), in Scheveningen near The Hague where the Nazis locked up Jews, resistance fighters and other people who violated the Nazi regulations. While in prison he was brought daily to the parliament buildings, het Binnenhof, in The Hague (where the Germans had set up their own administration) for further questioning. Here, he played a clever game. He was taught to come up with a clear straightforward story and stick to it. To give himself time to think about his answers he pretended not to fully understand his interrogator. In this way he also managed to give little away about the SOE organisation, even though he was presented with a death sentence without trial. He would worry about that later.

Typical cell – Oranjehotel Museum, Scheveningen, The Hague. (iii)

His execution would take place on October 26th but Ab didn’t wait for this event to happen.

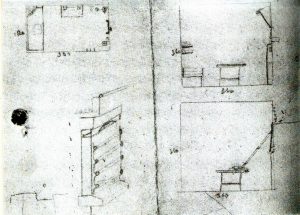

Ab’s detailed escape plan, written on the reverse of his prison registration card. (i)

He worked out an escape plan and two days before he would face the firing squad, he managed to escape from his cell. By propping up a ‘wooden detachable board on his wash stand with the aid of a lavatory seat, he improvised a ramp leading to the lower ledge of the high-set window’ in the entrance wall of his cell, according to his own statement in an English report. Now he could reach a barred window above the door, which could be opened. With a metal spoon sharpened with pieces of razor blades he received every morning to shave himself, he had whittled away the upper portion of the wooden window frame over the top bar. Who knows if his lessons in Fieldcraft came in handy here but however it may be, in this way he had created an opening just large enough to squeeze through. Dressed in nothing but his underpants, to avoid getting stuck with his clothes, the skin of his back was cut open in the process. Via a lower flat roof (the ceiling of his cell’s corridor) and two four metre high prison walls he made a dash for freedom, again. At 4 o’clock in the morning Ab hurried to his friend Jan de Haas, who lived at Elspeetstraat 12, in The Hague, about an hour’s walk from the prison, where he laid low for a while till his wound was healed.

Oranjehotel (Orange Hotel) under German occupation at Scheveningen

His absence wasn’t noticed by the guards until after his escape and a manhunt swiftly followed. For a while the police kept the addresses of his family under close surveillance and two of Ab’s other contacts became the focus of their warm attention as well. Their names were the only ones he had disclosed under torture but Ab had the wisdom not to turn up at any of these locations and he kept in hiding at several other venues. For four months he only left the premises at dark to continue recruiting contacts and gaining intelligence about the economic and social situation in the Netherlands which he did with ever growing secret-agent-feelers. Apart from his friend Jan de Haas he also found another friend, Jo Buizer, willing to join the Secret Service.

Meanwhile, word of his escape raised suspicion among other agents, his friend Cor Sporre being one of them. During their training they were taught that an ‘escape’ could mean the fugitive agents were now working for the Germans. When Cor and a fellow agent planned their exit back to England in an eight metre long motorised canoe, they didn’t invite Ab on board. Even their direct enquiries with Ab himself to explain his escape from prison had not convinced them of his total loyalty so they left without him. Lucky for Ab because the two agents never arrived in England after they left on November 13th 1941 and it is thought they drowned in the North Sea.

Ab was now left on his own but SOE desperately wanted him back in England since he had become a liability being on the black list of the Germans. On November 7th, a week before Cor left by boat, two new agents were parachuted to look for Ab and help him getting back. This operation, called ‘Catarrh’, was carried out by Huub Lauwers and Thijs Taconis. This time the agents were in the possession of a radio transmitter but, after the jump, it turned out not to work. It took a long while before the defect was discovered and repaired by a student friend: the culprit was a faulty wire which had not been spotted in England. However, when Lauwers, the wireless operator of the team, was finally able to contact London on January 3rd 1942 with the message that he had found Ab, his transmissions were picked up by the enemy. But it was not until March 6th that the Germans were able to locate and arrest Huub Lauwers at his transmission location in The Hague.

Huub Lauwers – the radio operatior, who stayed behind.

During this time Ab, assisted by Huub (unaware that the Germans were hot on his heels), worked out a cunning plan to return to England together with Jan de Haas and Jo Buizer. This second escape was again to be carried out from the harbour of IJmuiden.

Although fishing trawlers were under tight surveillance by the Germans they were still able to sail. With the help of his relatives Ab found a skipper willing to hide him and his two friends in the cargo of his trawler, called “Beatrice”. The plan, of which only the skipper and his cook knew and had agreed to beforehand, was that once well out at sea, the three stowaways would hijack the ship and force the crew to sail on to England. This audacious plan hinged on the promise of financial support to be paid out to the families of the fishing crew who would otherwise be without income until the end of the war.

SOE, intent on hauling Ab back in and also have two new agents at their disposal, agreed to paying out a total sum of 15000 guilders (worth about £46000 today) of which a third was destined for the crew’s families.

The 180 tonne Dutch trawler “Beatrice”. (viii)

On the night of February 15th-16th the three men – Ab Homburg, Jan de Haas and Jo Buizer – were smuggled on board the trawler once the coast was clear, that is to say after a German guard in the harbour was filled up to his eyeballs with alcohol and was now snoring his inebriation off. The next day at 2 o’clock in the afternoon the vessel sailed from IJmuiden. So far, everything was under control. Only when the journey’s moment suprème approached were they not so in control anymore. After sailing for some time, the three passengers, hidden in the smelly innards of the ship, were so seasick that, “…threatening the captain was out of the question, so they explained their predicament to him”, according to Ab’s post-arrival statement. It was now down to the skipper to convince his ten-man crew to proceed to England pointing out they could not return home before the end of the war. After several hours of deliberating, the promise of financial support for their families won them over and the next day, February 18th, they landed at Great Yarmouth.

Later, fake news was sent into the world that the ship had run into a mine, to avoid suspicion about its whereabouts. In addition to the pay out of bribe money the relatives could now also look forward to a survivor’s pension. For some time to come the crew and Ab kept in touch because now and again the skipper posted some fish to Ab caught in English waters.

While Ab Homburg, Jan de Haas and Jo Buizer were safely back in England and able to update SOE with a wealth of new Dutch intelligence, the notorious Englandspiel, the ‘game’ which involved the entire infiltration by the Germans of SOE operations in the Netherlands, unfolded. When the Germans finally located Huub Lauwers in March, he was imprisoned in the same Oranjehotel where Ab Homburg had been locked up. Here, under German duress, Huub sent several coded messages to London but he left out the security check, as per the instructions he had been taught by SOE, to indicate something was amiss. However, not only this warning but also numerous consecutive ones were overlooked at the British side.

Jan de Haas, Jo Buizer and Ab Homburg – London 1942 (i)

Eventually, even when suspicion first arose at the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), this vital information was not brought immediately to the attention of its SOE brothers. Because of this spectacular neglect – some suspect it was deliberate – many more agents landed more or less straight into the arms of the Nazi’s, as SOE announced their arrivals via now infiltrated channels. When the ‘game’ ended in May 1944 fifty two out of fifty seven agents had been arrested and sent to concentration camps. Most of them were executed and only nine, including Huub Lauwers, survived the war. Jan de Haas and Jo Buizer were not among the lucky ones.

Back in England it seemed wise for obvious reasons that Ab would not continue his career as a secret agent but there were more branches where daredevils were needed. A pilot with the RAF was his next occupation of choice but first he married his Pamela who had been waiting five months for his return from ‘whatever-he-was-doing’ on his secret mission. On August 28th 1942 the happy couple were united in matrimony . Witness was Willem de Waard, Ab’s childhood buddy who had joined him on his first sailing to England.

Pamela Boreham and Ab Homburg – 28th August 1942. (i)

Although it was the start of a happy time Ab’s life didn’t enter calm waters. Contrary to the general rule where RAF pilot training took place in Canada, USA or South Africa, Ab spent his entire pilot training in England because SOE needed to have him available in case further consultation was necessary. In the last stage of his training he miraculously survived a spectacular ditching in the North Sea. Shortly after take off his engine failed as well as his hydraulic system. Ditching was the only option but, with his landing gear still down upon touchdown, the aeroplane immediately overturned. Fortunately, the event was witnessed and when the coastal rescue service, almost certain that the pilot hadn’t survived this crash, went out to pick up his body they found him bobbing up and down in his dinghy, alive and without injuries.

Pilot Officer Ab Homburg with his wife Pamela with their son Clive – February 1944. (i)

Two weeks before Pamela gave birth to son Clive, Ab finished his pilot training and joined No.322 (Dutch) Squadron RAF on 1st February 1944. As a safety measure to protect his family in case of another capture by the Germans, he flew under the alias of Harvey. The Dutch fledgeling fighter squadron flying Spitfires had only just become operational. Shortly after Ab’s arrival the squadron’s rickety equipment was replaced with the super fast Mark XIV. Together with 91 Squadron, the unit was the first to fly the latest model of the Spitfire stable. Even for experienced pilots this aircraft was ‘a hairy beast to fly’ as their squadron leader, Keith Kuhlmann, put it and certainly not an easy machine for a new pilot. Ab was placed in B-Flight under Flight Commander Jan Plesman, son of Albert Plesman, the founder of Dutch Royal Airlines, KLM. Jan Plesman was a rather grumpy character but nevertheless Ab, by now tried and tested in the realm of stress, performed well under his command.

Pilot Officer Ab Homburg RAF. (i)

In a way Ab was lucky that the squadron’s first role with its new ‘race horse’ turned out not to be challenging in terms of a showdown with the enemy. In the run up to the invasion No. 322 Squadron was tasked with defending the sky above the south of England to hide the gathering of troops and invasion material in that area. However, much to the disappointment of the squadron, it was very quiet in the sky on the defensive front, at least by daylight when the Spitfires operated. The squadron’s main concern was a growing shortage of spare parts as a result of technical problems with the powerful Griffon engine. A week before the invasion Ab was plagued by a bout of engine trouble but he successfully carried out a belly landing at Bognor.

D-day itself also turned out to be an anti-climax for the Dutch 322 Sqd pilots in terms of their contribution to this gigantic operation which had been anticipated for such a long time. Apart from a few defensive patrols over the Isle of Wight area the squadron’s input was not needed. “All dressed up but nowhere to go” Squadron Leader Kuhlmann wrote in his diary disappointedly. Fortunately, from the sky they were at least able to catch a glimpse of the impressive fleet sailing towards the French coast.

But a week after D-day there was a major change in the not very spectacular role of the squadron when Germany started its retaliatory V-weapon launch from the northern coast of France. It soon became clear that only the fastest fighter aircraft would be able to intercept these unmanned, mysterious monsters – the ‘flying bombs’ or ‘divers’ – with their fiery tail and grumbling sound, before they dropped down creating havoc in towns and cities, mostly London. When given the assignment of ‘anti-diver’ patrols the men of No. 322 Sqd finally had an opportunity to prove their worth which they did indeed.

Princess Juliana of the Netherlands with Sqd Leader L.C.M. (Kees) van Eendenburg and a Supermarine Spitfire Mk.XIV of No. 322 “Dutch” Squadron at RAF Deanland, 26 September 1944.

Together with No. 91 Squadron RAF, also equipped with Mark XIV’s, they moved to RAF West Malling and later to an Advanced Landing Ground near Deanland where they became very successful at the “Diver hunt” thus saving the lives of many people. Suddenly however, at the beginning of August the Diver assault dried up considerably. With the speedy advance of the allies towards the Belgian border the German armies were forced to clear their V-1 launch sites along the French coast causing the sudden drop in the seemingly never ending attacks.

No. 322 “Dutch” Squadron RAF – RAF Deanland, East Sussex – Amongst other pilots Ab Homburg (with white scarf) meets Princess Juliana of the Netherlands 26th Sept. 1944 (i)

The Dutch squadron now entered a new era by exchanging its defensive role above the south of England for an offensive one involving armed reconnaissance missions above northern France. Although the pilots had done a very good job intercepting the V-1 attacks they still felt that so far the war had passed them by. The very reason for most of them to risk their lives in coming to England was to give the invaders a good beating. With their new tactical role this wish seemed to be fulfilled.

However, they had to hand in their beloved Mark XIV because their new assignment above occupied territory required another type of Spitfire. The low level flying Mark IX was fitted with an extra fuel tank underneath the belly to increase its range and the exchange of aircraft took place on 9 August.

At the end of his first flight with his ‘new’ Spit, Flying Officer Homburg had a very unfortunate landing at RAF Deanland. His belly tank, still heavy with fuel, hit the ground and his aircraft caught fire. However, Ab had his lucky angel still sitting firmly on his shoulder and he managed to leave his aircraft in time. Perhaps his parachute jumping skills kicked in because a squadron colleague joked “I have never seen him jump out of his Spitfire that quickly”. With only light burns on his face and hands Ab was taken to Eastbourne hospital.

No. 322 Squadon at RAF Biggin Hill, 1944. Ab is middle row 2nd from left. (v)

Soon the Squadron’s new tactical role took a heavy toll. Its hunting ground during the second half of August shortly before the liberation of Brussels and Antwerp, was near the Belgian border. This area was heavily defended by German flak.

With Ab Homburg still on sick leave No. 322 Sqd. lost its entire command on 1st September 1944 as a result of direct hits of flak. Squadron Leader Keith Kuhlmann was hit but baled out with his parachute and survived as a prisoner of war. Flight Commander Jan Plesman crashed and was killed. The other flight commander, Kees van Eendenburg, survived his belly landing and with the help of the French resistance returned to England after a week. Upon his return he was appointed to replace Squadron Leader Kuhlmann. The task fell to him to lead the squadron in the liberation of The Netherlands starting with the Battle of Arnhem. Because this battle ended in a debacle the squadron saw its long anticipated move to the continent shelved again till the allies had a firm footing on Dutch territory. The crossing over would take place, at long last, on New Year’s Eve.

Flight Commander Bob van der Stok briefing his crew, 1945. (v).

Ab moved with the squadron to its new base at Woensdrecht. With the end of the war in sight the separation from Pamela and baby son Clive would hopefully not be for long. During these final four months of the war Ab served under a new squadron leader, Bob van der Stok, who had made a spectacular escape himself from a prisoner of war camp in Nazi Germany, now known as ‘The Great Escape’. In his effort to give the squadron a necessary boost for the final stages, Squadron Leader Van der Stok replaced some of the longest serving 322-veterans with fresh blood. Due to a shortage of new Dutch pilots English personnel filled the gaps. In spite of this boost, the squadron suffered more losses in this phase than during its entire time in England.

No. 322 (Dutch) Squadron RAF at Woensdrecht, North Brabant, Netherlands 1945 – Ab is front row 2nd left. (i)

On April 1st 1945, one month before the end of the war Ab took part in an armed reconnaissance mission over the border area of The Netherlands and Germany. Flak concentrations were higher than ever before and an extra complication was a very poor visibility due to low clouds (the cloud base was between 500 and 1000 feet). Nevertheless Group Command ordered missions to go ahead to prevent the enemy from regrouping their troops for a counter attack. “The squadrons were ordered to spare no effort in shooting and bombing targets”, one of Ab’s colleagues wrote later. During this mission four aircraft of No.322 Squadron were hit and went down. Of these four Ab Homburg was the only one who did not survive.

His wing man, Warrant Officer J.S. Morden, last heard him near the German town of Münster before he lost contact. Eye witnesses on the ground near the Dutch town of Bornebroek, roughly a hundred kilometers to the east of Münster, saw his machine coming down trailing smoke before it hit some trees and crashed into the ground. According to an expert involved with airplane wreck salvage, Ab had tried but failed to land his Spitfire.

After two escapes across the North Sea and numerous other escapes from death, 27-year old Ab Homburg had finally run out of luck one month before the war ended. He was one of the last pilots of the squadron who did not survive the war. Squadron Leader Bob van der Stok wrote ‘Appie was a very special guy. I have rarely seen somebody with so much courage and perseverance. His history is almost unbelievable’.

Not long after the war Pamela moved to The Netherlands with her son Clive to live near her husband’s family who supported her in whatever way they could and she remained in The Netherlands for the rest of her life.

Ab Homburg’s funeral courtège. He was reburied at The Honorary Cemetery, Duinhof at his hometown IJmuiden. (i)

Story: Anke ter Doest – 2022.

With a Dutch Master’s Degree in the History of Art, Anke has spent a considerable part of her life in the Netherlands writing and teaching about art related topics. Living in the United Kingdom since 2010 she has co-written a book about the wartime adventures of her father who escaped to England from the Netherlands as a sixteen year old, to join the allied war. “The Road to England”, will be published in the near future, initially in Dutch and later in English.

During her research she became fascinated with the story of Ab Homburg who was a pilot in the same No. 322 (Dutch) Squadron as her father when he served as a ground mechanic before becoming a pilot himself.

.

AFHG/GPFA Production: Ian Reed.

Bibliography:

Johan Graas, Ab Homburg. Vergeten Soldaat Van Oranje, 2019

Frans Becker en Tamara Becker. De eerste geheim agenten van SOE, 2020 https://www.wiardibeckman.com/post/agenten-van-soe

Frans Becker en Tamara Becker, SOE tast in het duister, 2020 https://www.wiardibeckman.com/post/soe-tast-in-het-duister

Deborah Nickolls-Lee. www.dutchnews.nl/features/2022/02/new-research-puts-names-and-faces-to-victims-of-february-1921-razzias/

Jim Fish, Uncovering the game against England, 2004 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/3324807.stm,

Wesley Dankers, England game, 2016 https://www.tracesofwar.com/articles/4706/England-game.htm

Michael Foot, SOE in the Low Countries, 1998

Michael Cunningham, Beaulieu. The Finishing School for Secret Agents, 2005

Alan Malcher, Now it can be told: School for Danger (public information film), 2020 https://alanmalcher.com/2020/07/17/now-it-can-be-told-school-for-danger-public-information-film/ Alan Malcher, Dutch resistance 1941-1943: SOE’s greatest disaster in occupied Europe, 2021.

Filip Appeldorn, 40 jaar 322 Squadron, 1943-1983, jubilee publication without date

Erwin van Loo, Eenige Wakkere Jongens, 2013

Erwin van Loo, Kat en muis spelen met de bezetter. Hans van Roosendaal

Archives

AFHG/GPFA Archives

National Archives, Kew via company archive Explosive Clearance Group B.V. Wijchen – SOE dossier HS9/737/4 A.A. Homburg.

National Archives, Kew, Summaries en Records of Events, 322 (Dutch) Squadron

Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, dossier Ab Homburg

Email :

C. Cornelissen jr., Almelo, clarification concerning crash A. Homburg, 27.o1.2022

Paul McCue, clarification on Homburg’s training as a secret agent, 03 & 04.02.2022

Pictures

Unattributed: AFHG/GPFA Archive or Common

(i) Family Homburg granted via Johan Graas

(ii) Paul McCue, Secret WW2

(iii) Nationaal Monument Oranjehotel

(iv) Nederlandse Oorlogsgravenstichting

(v) Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire History Collectie (NIMH).

(vi) Het Noord-Hollands Archief

(vii) Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie

(viii) Johan Graas

Superbe récit.

A very interesting, lively and detailed account of the wartime years of a brave and mysterious man.

Fascinating and humbling in equal measure.

Very interesting and well researched. Read it with pleasure.

What a remarkable story..It makes me realize again how much we owe those brave young men who gave their lives for our freedom.

What a remarkable and well researched story. How incredibly brave those young men were.

Had a great time reading this, a lot of history I never knew about Ab Homburg. Interested in reading more!