How a Young Free-French Pilot helped save an English City – Yves Mahé

At 23, Yves Mahé had already escaped the NAZI’s, now he was flying flat out to save an English city.

It was 29th April 1942, Yves Mahé was just 23 years old and had already experienced more than most people. As a pilot in the Armée de l’Air as it was overrun by Axis Forces in May and June 1940, he risked capital punishment to escape and carry on the fight in England. But on this April night in the skies above the historic City of York, it would be one of the most testing experiences of his life.

Born in Nantes, Loire-Atlantique, France, on 21 November 1919, Yves qualified as a civilian pilot and then joined the French Air Force at Istres when war broke out in 1939. The Battle of France began in May 1940 and the French and their British allies fought for every inch on the ground and in the air. Within a month the RAF and the French Air Force had lost over 1800 aircraft as the Germans continued to push onwards.

Following the evacuation at Dunkirk, the French Air Force fell back to their bases in North Africa to regroup. France had sustained over 300,000 casualties in just 5 weeks, and on June 12th an Armistice was declared by the new French government to be based in Vichy, under Marshal Pétain.

Sous Lt. Yves Mahé ©LM

Meanwhile in Algeria many of the French aviators wanted to fight on, but by now the Armistice agreement with the Nazis meant that to do so was treason, punishable by death. Despite this many airmen tried to escape to join Britain. On the night of 1st and 2nd July, after several attempts, Yves Mahé and others stole an aeroplane and flew across the Mediterranean to Gibraltar, where on 7th July they were able to take a ship to England.

In Britain, Yves joined General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces and the group of French pilots who had managed to escape Occupied France.

Yves Mahé (on far right) in England – 1941

In a curious footnote, Yves’ brother, also a pilot, had escaped at exactly the same time but via a different route posing as a Polish officer. Both brothers met quite by chance on their first day in England, whilst sight-seeing in London!

Yves Mahé with French airmen re-training for RAF aircraft types & procedures. ©LM

Now in Britain, they were inducted into Royal Air Force Fighter Command where Yves re-trained on Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft. In 1941 he was posted to No. 253 (Hyderabad) Squadron, which was based in the Orkney Islands in the far north of the UK and in late 1941 his squadron moved to Lincolnshire where they flew convoy protection missions in the coastal regions of the North Sea and English Channel.

Hawker Hurricane fighters

The Baedeker Raids

Following the Fall of France and the Battle of Britain during 1940 the Luftwaffe concentrated its might upon British cities in an attempt to destroy manufacturing facilities and break public morale by Blitzkrieg.

As well as London, other strategic cities like Kingston upon Hull, Liverpool, Birmingham, Sheffield, Southampton, Portsmouth, Glasgow and many other, suffered terribly with large numbers of civilian casualties and the destruction of buildings.

Coventry after the raid in November 1940

On the clear moonlit night of 14th November 1940, the City of Coventry suffered one of the most concentrated attacks of any British city. For 11 hours over 500 German bombers dropped 30,000 incendiaries, 50 landmines and over 500 tonnes of high explosive bombs. The devastation was immense. It even coined a new word in the German language: “coventrieren” – to raze a city to the ground.

Britain stood alone as the bombing attacks continued and intensified. In the early days the largely obsolete, slow and relatively low flying RAF Bombers suffered large losses and were easy targets for German anti aircraft fire and modern fighters. Their first missions were often leaflet drops in a vain attempt to persuade German opinion, but as the development of new aircraft types became available and British cities continued to being pounded, Prime Minister Winston Churchill called for the “...bombing of Germany day & night”, in order to take the initiative back to the Continent.

Air Marshal Sir Arthur T. Harris RAF

In February 1942 he appointed Air Marshal “Bomber” Harris to undertake this task and to lead the RAF bomber forces to take the War back to Germany. Harris was determined to focus efforts, take the initiative and give the British and occupied peoples of Europe some hope and confidence that all was not lost. He made the famous statement:

“The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everyone else, and nobody was going to bomb them. At Rotterdam, London, Warsaw and half a hundred other places, they put their rather naive theory into operation. They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind”.

Public pressure for an initiative was now on Harris’ shoulders and the following month he approved a plan for a concentrated attack on the Hanseatic City of Lübeck on the Baltic coast. The location was chosen because of the safer route mainly over sea and the limited flight times of the current aircraft available at that time. 234 bombers attacked the city for 2 hours creating a fire storm which destroyed much of the medieval central area including 3 churches.

Lübeck Cathedral receives a direct hit – April 1942

In response, Hitler’s speech to the Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House, warned that reprisal attacks were on their way. “This man (Churchill) will not again wail and whimper as I am now forced to give a response that will bring much suffering to his own people. From now on, I will retaliate blow for blow until this criminal falls and his work dies.”

NAZI propaganda blamed Britain for attacking historic places which had no strategic value, and their response was immediate: ‘We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide’ – the standard German tourist guide for historic places to visit.

The Baedeker Tourist Information Guide.

Initial retaliatory raids took place against coastal towns including Torquay, Bognor Regis, Swanage, Portland, Exmouth, Bexhill, Folkestone, Hastings, Lydd, Dungeness, Poling, Cowes and Newhaven.

What was soon to be called the “Baedeker Raids” began in force nine days after Hitler’s speech. First was Exeter on 23 April although only one bomber found the city. The following night Exeter was attacked again. In 2 hours, around 60 bombs and 2,000 incendiaries were dropped causing 130 casualties and almost 6,000 houses damaged.

The City of Exeter with the cathedral in the background – 23rd April 1942

RAF Bomber Command then attacked Rostock, aiming for the Heinkel and Arado aircraft factories, but also causing extensive damage to the city centre over four consecutive nights.

On 25 and 26 April, the historic Roman city of Bath was attacked in a series of intense raids killing over 400 civilians and the next day, Luftwaffe aircraft, now operating from bases on the Netherlands coast attacked Norwich creating over 750 casualties.

The historic city of Bath – April 1942

The next target was to be York…..

The huge Gothic cathedral of St. Peter at York – York Minster

The City of York lies within a large plain known as the Vale of York, bordered by the North Yorkshire Moors to the north, the Yorkshire Wolds to the east and the Howardian and Hambleton Hills to the west. Its military past was founded by the Romans in AD71 as Eboracum, the place where Constantine the Great was first declared Emperor in 306AD and later, as Yorvik, the city became the Viking capital of Britain. In the 11th century two motte and bailey castles were built by William the Conqueror straddling the River Ouse flowing thought the centre of the City. It was the historic second capital of England with the largest Gothic cathedral in Northern Europe – the Archbishop of York being one of the two top posts of the Church of England.

29th April 1942

Like most towns and cities across Britain air raid precautions and practices had been carried out assiduously since hostilities began back in 1939. The large flat Vale of York was home to dozens of new RAF airfields, principally for bombers, and the large numbers of soldiers and airmen from all over the world were common sights in the streets and bars. Although there had been over 750 alerts, nothing had happened and there were few anti-aircraft defences installed. The city felt that it had been largely forgotten by the enemy – but this was all about to change.

Luftwaffe Dornier Do17 “flying pencil” bombers en route to a target

At 2:36 am on Wednesday 29th April 1942 around 80 Luftwaffe bombers – Junkers 88, Dornier 17 and Heinkel III’s, flying at around 200 mph were observed about 30 miles out at sea off the North East Coast heading North. Their target was unknown and this was a regular ploy to keep the British defences guessing until, flying in pairs or singularly, they suddenly turned westwards and crossed the Yorkshire coast at several locations between Flamborough Head and Whitby.

RAF nightfighters across the region were already patrolling the airspace as a normal defensive measure, when the Royal Observer Corps (ROC) look-outs observing the change of course of the bombers raised the alarm to “purple” which activated all the RAF night fighter stations in the region. The observers could not initially identify where exactly the attackers were bound, or whether they would again veer North to the industrial areas of Teesside, South to the Leeds and the West Riding complex or West towards Manchester and Liverpool, but it was soon to become clear what their intentions were.

RADAR was still only used to look out to sea and the widespread integrated ROC system of civilian look-outs on hills in tree-tops and on top of large buildings began the search of the skies listening for the drone of incoming bombers.

Volunteers of the Royal Observer Corps identify and obtain direction speed and height of incoming aircraft across Britain. They were an integral part of Britain air defence system.

Night fighter squadrons in airbases across Yorkshire and Lincolnshire were already on high alert as around 40 bombers followed the moonlit River Ouse towards their target.

As they began to arrive over the City their initial tactic was to drop incendiaries onto the roofs of buildings to begin fires and light up the target before the high explosives were dropped. For an incredible 90 minutes bombers circled the City as they identified their targets and dropped their bombs.

The railway station was a principal target as York was on the main East Coast railway line almost half way between London and Edinburgh and was the main route to northern sea ports for military equipment supplying Russia and the Eastern Front – all of this well known to the German planners whose army was currently fighting a war of attrition against Soviet forces which had counter attacked and pushed back the Germans during the winter of 1941.

The main concourse at York Railway Station after the raid.

The express train from Kings Cross had pulled in at 02:53 packed with soldiers, and a direct hit from a 100kg high explosive bomb smashed into the main concourse. Three railwaymen and an unknown soldier managed to disentangle the coaches and allow a shunter to pull 14 coaches out of the burning station, leaving six still burning fiercely. A signalman commandeered another steam shunter and pulled a further 20 coaches, on another track, out from the flames whilst other bombs hit the engine sheds and surrounding tracks and installations.

The York Engine Shed “Roundhouse” sustained severe damage. Several steam locomotives were hit including the famous A4 Pacific “Sir Ralph Wedgwood”.

Meanwhile fires were burning in hundreds of buildings throughout the City as the raiders circled above unmolested, and the stream of new bombers arriving continued to add to the destruction below.

The nearby aerodrome of RAF Clifton, which was a Handley Page aircraft repair factory, was attacked causing widespread damage and injury. The guard room received a direct hit and several other buildings were destroyed. Seven airmen were killed and nine wounded. An unexploded bomb later killed a further Bomb Disposal officer the next day.

The City was home to three famous cocoa and sweet manufacturers (Rowntrees, Cravens & Terry’s) and one of Rowntrees’ storage warehouses by the river had already caught fire, the huge amount of stored sugar burning fiercely in the night sky.

The Guildhall built in the 1450’s was, following the attack on its London counterpart a few months earlier, now the oldest in England. Within its walls had walked many famous names throughout history, from King Richard III to Queen Victoria and it was here where the ransom, famously paid to the Scots for King Charles I, was counted in 1647 at the end of the English Civil War. The ancient building lined with oak panelling received direct hits and was soon engulfed in flames.

By the side of the River Ouse, York’s medieval Guildhall engulfed in flames.

Several RAF aircraft were already in the air searching the skies. Five night-fighter squadrons had been activated including No.133 “Eagle” Squadron RAF, comprised of US pilots who had joined the RAF before the USA had joined the War.

No. 253 (Hyderabad) Squadron based at RAF Hibaldstow in Lincolnshire had a number of Free French pilots, and as the Luftwaffe raiders approached the City, Lt Beguin had already taken off with two British colleagues and was heading towards York.

Around 40 minutes later Yves Mahé took off with 5 other Hurricane fighters and seeing the glare of fire in the sky 60 miles to the North, raced off in the direction of the City.

Hawker Hurricane Mk.II fighter

Around 10 minutes later he was diving down from 6000 feet towards the City at full speed (around 400 mph), when he immediately engaged a Ju.88 bomber and closed to attack it. Mahé attacked with his four 20mm cannon blazing and riddled the bomber’s tail and fuselage, as its machine gunner fired back at him. Mahé continued the attack. “I gave him a taste of his own medicine and his fire ceased“, he later exclaimed. The bomber was on fire, and as it spiralled down some crew members bailed out, each one unfortunately hitting the tail of the bomber, although most survived, as it plummeted down to eventually crash just south of York.

Heinkel III twin engined bomber

The sight of the bomber being shot down and Mahé’s intervention along with his comrades caused the other bombers to begin to break off the attack as Mahé curved to engage a further aircraft which he attacked causing it to suddenly dive. He lost contact with it but during the attack he had narrowly over flown another Ju88 bomber which was targeting the main Rowntrees sweet factory to the East of the city centre.

Rowntrees main factory in the City was huge and whilst food and sweet manufacture continued in the multi floors above ground the vast basement area was secretly confined to munitions and explosives.

The Luftwaffe bomber pilot said later that he “was simply aiming at the biggest factory” when suddenly Mahé flashed overhead with his guns blazing. The German broke off the attack, dropped his bombs indiscriminately to lighten the load, and escaped. Had the bomber hit his target is has been surmised that the explosion of the tonnes of stored munitions could have flattened much of the centre of the City including the famous Gothic cathedral.

The faster Junkers 88 light bombers, along with the Dornier DO.17 ‘s were in the vanguard of the attack followed by the slower and heavier Heinkels.

Having pressed the engine on his Hurricane over its maximum limit during the attack, Mahé’s aircraft now began to falter and fail, he veered off and eventually managed to land at nearby RAF Church Fenton as his engine began to seize. But he and his fellow fighter pilot’s interventions had a big effect as the bombers immediately began to disperse. The bombing stopped, and as other RAF fighters were appearing and attacking the bomber streams, the attack on York quickly came to an end.

Yves Mahé’s Pilots Log Book with his description of the attack ©LM

Wednesday April 29th 1942 at 2:45 in the morning we received the order to fly. We take off from Hibaldston for York - being attacked by a heavy bombing raid. Just 5 minutes after my arrival above York I perceived a Junkers 88, or at least I thought it was, but I was not able to catch it up. 10 meters later I saw a second one. I approached it from behind and a little bit underneath, and at 50 meters I fired a burst of my 4 cannons. I saw it flit into pieces and engage in a violent fall. I follow it until 3,000 feet, but despite the moonlight I lost it. Though I thought I got it? 5 minutes after, I found what could be a HEINKEL III. A good burst of fire at 50 to70 m and I am on a vertical dive in which I disengaged from it. I send it 2 complementary bursts and I loose it at 1000 feet . Then my engine gives me concern and I am forced to land at Church Fenton". (Note: see the end of this article to view his Official RAF Combat Report)

RAF fighters from various bases had already been searching for the both the incoming and outgoing bombers all along their route from the coast where they came across them in the dark. Around 5 bombers were known to have been brought down and several severely damaged.

Meanwhile as dawn began to break the old City began to count the cost.

Clifton district of York – the day after

During the night over 84 tonnes of bombs had fallen on the City. There were over 300 casualties and at least one third of the City’s buildings had been damaged or destroyed including 9,500 homes and the famous medieval Guildhall and church of St Martin-le-Grand, the shell of which stands to this day as a permanent memorial to the raid – its famous clock stuck at the time the church was bombed.

St. Martin-le-Grand, Coney Street was gutted by fire.

At the Bar Convent School close to the railway station, five nuns were killed. A further seven schools were also badly damaged.

Bar Convent, Nunnery Lane. Across the road to the right is the railway station.

Over 1000 civilian air raid (ARP), fire fighters, police, medical organisations and volunteers had worked through the night to put out the fires, attend to the casualties, rescued those in need and helped support the survivors. Extraordinary feats of personal bravery took place amongst the civilian population and emergency services. Some gave their lives to help others. The subsequent inquest summarized that “….without hesitation, that on the whole, the services and the citizens acquitted themselves well”.

The district of Nunthorpe, York

Because York had not been seen as an important target the air raid warning sirens were operated from a central control outside the City and did not sound until the raid was already well underway. By the time the “white” signal was given and the air raid sirens began their long continuous drone to announce the raid was over; it had been around 2 hours since the first bombers had appeared over the East Coast.

As a result of the raid, defences for the City were increased dramatically, although no further raids of any significance occured for the rest of the War.

The Yorkshire Evening Press shortly after the raid in 1942

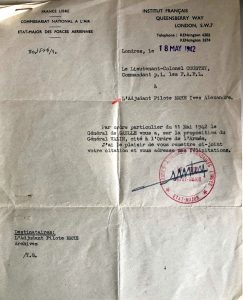

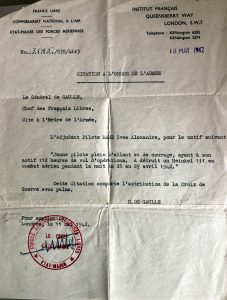

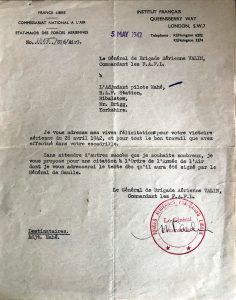

Yves Mahé later attended a civic reception and received the Freedom of the City by the Rt. Hon. Lord Mayor at a special event, and the French tricolour with the Cross of Lorraine flew over the Mansion House. This had been the first time he had shot down an enemy plane and on 11th May 1943 he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre with palm by General de Gaulle. Later de Gaulle was again to decorate him as a Companion of the Order of Liberation, awarded to only 1038 Free French.

Letters from General de Gaulle & Chief of the Free French Air Force, General Valin ©LM

In August, Yves transferred to the famous French Normandie-Niemen Squadron which flew Russian YAK 3 fighter aircraft with the Soviet Air Force on the Eastern Front. He was shot down over Smolensk, captured by the Germans in May 1943. After numerous escape attempts he was condemned to death on 15th August 1944 by a Luftwaffe court in Dresden. He attempted to escape but could not get out of the prison compound. With the aid of fellow prisoners he lived in secret inside the prison camp for 9 months narrowly evading capture several times, until the camp was eventually liberated on 25th April 1945.

Upon release he was seconded by the Soviet forces as a deputy Colonel to assist with the repatriation of French forces and in the following August he, at last, returned to France.

Yves Mahé – the Normandie-Niemen squadron badge is on his left side pocket

After the war he continued flying with the Normandy Squadron of the French Air Force eventually becoming its commander in 1952 after service in Vietnam. In 1956 he took command of the 5th fighter Wing based at Orange. He returned the English skies above York once again during training exchanges and commented that “I know English skies well”! He was promoted to Lt. Colonel and was assigned to the Air Defense Operational Center at Base 921 Taverny, but was sadly killed on 29th March 1962 in an air accident flying a Gloster Meteor jet fighter over Boussu-en-Fagne in Belgium and was buried at Issy-les-Moulineaux in Paris. The former air force base, 20km from Paris was later renamed “Frères Mahé” after the two brothers.

Yves had flown over 730 hours of which 140 hours were during combat

He was 42.

“The stuff of legends”

– H.E. Bernard Emié, French Ambassador to the United Kingdom – May 2014.

The Blue Plaque opposite St Martin-le-Grand unveiled by the French Ambassador to UK, His Excellency M. Bernard Emié on 2nd May 2014.

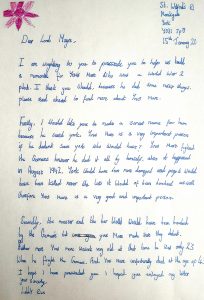

In 2012 the children of St Wilfrid’s School in York began a project with their teacher Dan Jones to learn about the raid. The children later wrote to the Lord Mayor of York on the 70th anniversary of the raid asking that Yves Mahé should be remembered in some way.

In co-ordination with York Civic Society and Yorkshire Air Museum a blue plaque was unveiled on the wall opposite the remains of St Martin-le-Grand in Coney Street in 2014 by the French Ambassador to UK, to commemorate the young French pilot who helped end the Baedeker Raid upon York in 1942.

H.E. Bernard Emié, (French Ambassador to UK) on left, accompanied by Ian Reed (Director YAM&AAFM) & Dr Peter Addyman (York Civic Trust), with children of St Wilfrid’s School, York – 2nd May 2014. ©IPR

In October 2011 a memorial was installed in York Minster to the French Air Force Bomber Groups based in the City during WWII. The French tricolour flies over York Minster and RAF aircraft fly past in formation to honour their French Air Force colleagues – 20.10.11.

The French flag flies above York Minster as the RAF pay tribute the the French airmen October 2011

AFHG/GPFA – 29th April 2021

Produced and written by Ian Reed

French translation by Geneviève Monneris

With grateful thanks to Yves son, Loïc Mahé

Click here to return to Projects Page

Click here to return to Projects Page

Further information video and appendices :

For further detailed information on the York Raid we commend this website: https://www.militaryhistories.co.uk/york

APPENDIX 1.

Yves Mahés Official RAF Combat Report:

I took off from Hibaldstow at 02:50hrs 29/4/42 in Hurricane IIc, vectored 345 degrees to York and orbit at 6,300 ft.

Whilst flying North at approximately 03:10h I sighted an E/A (enemy aircraft) which I believed to be a Ju.88 on my port beam and heading South at a distance of about 1000yds. I turned sharply towards him and gave chase but lost contact, partly owing to the fact that my windscreen was badly oiled. I came back to my position over York again, at the height assigned having reported my visual on R/T, at approximately 03:15hrs. I saw a small trail of flares dropping from about the same height as I was flying, slightly below. I proceeded with full throttle to the spot (going South West) and sighted the E/A at about 1,000 yds on my port side heading roughly S.S.E.

I gave “Tally Ho” and pulled the automatic boost cut-out, and at maximum revs and throttle dive-turned towards him, this bringing me approx 2000 ft below E/A, very slightly astern of his position. I then pulled up, therefore losing speed until I was sitting on his tail. Owing to my windscreen being oiled up I was rather in doubt as to whether it was a He.III or a Ju.88 (looking at his exhausts which were very bright and well spaced I first thought it to be 4 engined).

I adjusted my sight quite definitely and delivered a 2 second burst and saw a big flash and start of fire in his starboard engine. E/A then went into steep spiral dive, I followed him down to 3,000ft where I lost contact. The flames had then gone out but the E/A was still diving down, at least 300 mph.

As soon as I had fired I informed “Alarm” that he was going down. Their fix approximates to the position Ju.88 was found. I informed “Alarm” that I was going back to position. Whilst in orbit slightly N.W. of York a few minutes after reaching 6,300ft I saw a stick of bombs falling East of York, by their direction I assumed the E/A to be flying N. to E. I cut across York full out, having actually seen the 6 bombs in mid air giving away the E/A’s position. I obtained visual at approximately 1,500 yds at barely 03:25 hrs, thought to be He.III, I gave chase.

I gave “Tally Ho”. E/A being slightly on my port going roughly east. Having jettisoned his bombs he was going fairly fast, as I pulled the emergency boost cut-out again, and dived down to catch him up reaching a position about 2,000 ft blow and pulling up to sit on his tail, as in the previous combat. Approaching to about 70 yds, after careful aiming, I opened fire with 2 second burst dead astern, observing strikes on the E/A, seeing pieces fly off.

My windscreen being still oiled up, it was impossible to observe what parts flew off, but I did think it was something on E/A’s starboard side. I pulled up, being blinded temporarily by the explosion of my shells on E/A at short range. E/A immediately peeled off to my port very sharply as I observed what I thought to be a few tracers, (but may have been pieces still flying off E/A). E/A was then in vertical dive sliding from side to side. I followed down giving another burst of about 1 second, slight deflection.

E/A’s dive was very fast and I had to push the stick with 2 hands to follow. At 1,500, I closed still in steep dive to about 100 yds of E/A and gave him another 2 to 3 second burst from astern and I was again blinded by the strikes on the E/A, and as I was near the ground I pulled up, I pulled up losing contact. E/A was then going East still in fairly steep dive.

This chase brought us well East of York, at least 15 to 20 miles having engaged the E/A at about 6,500ft and going down with him to 1,000ft my A.S.I. was about 400mph. I turned back towards York gaining height, then being called up by “Alarm”, I answered “OK” returning to position and reported that I had had 3 bursts at E/A and lost contact.

I then looked at my instruments and as my oil pressure was showing zero, and oil temperature 110 degrees I asked for nearest base and landed at Church Fenton at 03:40 hrs. Both combats took place with moon behind me making definite identification difficult, and was also very surprised not to have been fired at when approaching.

I claim the Ju.88 as destroyed and the He.III as damaged or probably destroyed being fully convinced that the He.III could not have reached home.

(signed) Y.Mahé

7th May 1942

APPENDIX 2:

Part of a BBC documentary of the raid on York, which the author helped produce:

Mahe’s aircraft had serial BN292. But what was it’s squadron code at that time. SW-?.

The a/c code was “SW”. 253 “Hydrabad” Sq RAF – I hope that helps?

Amitiés

Caroline.

Thanks for confirming squadron code as SW, but what was the individual aircraft identifier?

Thanks for confirming squadron code as SW, but what was the individual aircraft identifier? That is the individual letter, specific to the aircraft, that appears after the roundel. The aircraft registration was BN292, and full details of production etc are easily available.