Ivor’s Flying Career and the Empire Air Training Scheme – Lord Peter Ricketts

An airman’s experiences in the largest air training project in history and how Ivor shot himself down in a Spitfire!

During World War II, over 150,000 operational airmen flew with the various units within the Royal Air Force. They flew as pilots, navigators, flight engineers, bomb aimers, gunners and radio operators in Bomber Command, Transport Command, Fighter Command and Coastal Command, as well as those who flew with the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm.

Wartime public reassurance poster

It was recognised well before hostilities began that this would be a huge task to train and qualify enough men to take on this task. With Britain located on the front-line and already crammed with operational airfields, it needed to look towards its overseas dominions to find the room and capability to train its young aircrew.

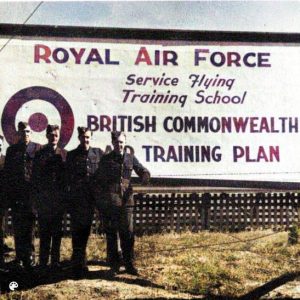

Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939, and in Ottowa on 19th December Lord Riverdale of Sheffield (Arthur Balfour) signed the Air Training Agreement with the British Dominions of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The Empire Air Training Scheme, later known as the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), was shortly afterwards joined by Southern Rhodesia and Bermuda and a parallel scheme, the Joint Air Training Scheme, was established in South Africa.

New recruits arrive in Canada – 1942

BCATP countries undertook basic training at their own air force establishments before sending their airmen to Canada to complete advanced courses. Training establishments across Britain were used throughout the War, especially for foreign airmen who had escaped the invasion of their countries. Even established foreign airmen who had more experience that their teachers needed to go through the system and understand RAF protocols, methods and aircraft types in order to be effective within their squadrons. Sometimes this cause friction but one French airman said that even when he could not understand English properly, the standard RAF phrases used on the radio could be understood even with poor reception, simply by their sound. A sound he would reply to with the appropriate response, even though he had no idea what words he was using!

By the end of the War the Empire Air Training Plan and BCATP had trained over 130,000 aircrews who flew with the RAF and FAA.

The scheme also trained airmen from France, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Argentina, India, Ceylon, Greece, Fiji, Norway and USA.

Airmen from over 16 countries flew alongside British airmen in the RAF – here at RAF Tangmere are airmen from Poland, Australia, Canada, USA and New Zealand

The inital, almost desperate, urgency to provide air defence from the time of the Battle of Britain, led to an over production of pilots and airmen as early as 1942. By 1944, there were at least 15,000 new recruits awaiting final flight training, with few places for them upon completion. In contrast the British Army, which had been fighting non-stop for almost 5 years was a reducing resource. As a result many airmen were moved to the Glider Pilot Regiment and trained air gunners were re-designated “Ground Gunners” becoming the Royal Air Force Regiment in February 1942 and seeing action on the ground in India and Burma and particularly in the Battle of Imphal in June 1944.

Although some 9,000 USA pilots had been trained “incognito” because of US neutrality, this changed in December 1941 and over 1600 allied pilots were trained along with USAAF aircrew in Miami and other locations across the United States.

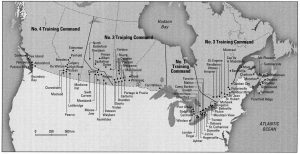

BCATP establishments across Canada

By late 1944 defeat of Germany was inevitable and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was brought to a close. It had been enourmously successful and had trained over 160,000 airmen. In Canada alone, there had been over 200 schools and supporting establishment across the country with a huge infrastructure of supporting personnel and equipment. The success of the plan eventually led to its extension following the end of the War, in the form of the NATO Air Training Plan and the current NATO Flying Training in Canada (NFTC).

However, during World War Two many young men who had completed their highly intense training courses over many, many months, particlularly pilots, found themselves almost redundant upon completion and unable to reach the challenges which had led them down this path, some never made it to the air again and others had to wait until their turn came.

One such young pilot was the late Ivor Horlington. His son in law, Lord Peter Ricketts, former British Ambassador to Paris, has put together the flight training story of Ivor, to give us an insight into the life and eventual career of one of these young BCATP pilots.

Ivor Horlington’s flying career: 1943-1972 – Peter Ricketts.

This account of Ivor’s 2,000 hours of flying with the RAF is reconstructed from his log books and photographs. It also tries to solve the mystery of why he came back from Canada as a fully trained pilot in the February 1944, but never saw operational service during the war!

Like thousands of other trainee aircrew, Ivor went out to Canada as a Leading Aircraftman (the lowest form of life) in July 1943. His first course was at 15 Elementary Flying Training School at Regina, Saskatchewan. He flew the Fairchild Cornell. Here’s what he called his ‘glamour shot’ of the plane:

PT 19 Fairchild Cornell Trainer

He flew solo after 10 hours and, after an 8 week course, transferred to 11 Service Flying Training School at Yorkton Saskatchewan. Here for four months he flew Cessna Crane two-engined aircraft, based on the Avro Anson. This suggested he was streamed for multi-engine aircraft (those headed for single-engine continued training on the Harvard). Ivor seems to have enjoyed flying the Crane. He took lots of pictures of flights over snowy Canada:

AT-17 Cessna Crane – 5 seat advanced trainer over the snowy wastes of Canada

Ivor (centre) with comrades in front of a Cessna Crane trainer 8824. This aircraft became operational at No. Ait Training on 13th June 1942. It had an RAF serial number FJ173 and was put into reserve status and then into storage at Estevan, Saskatchewan on 27th September 1944, where is remained until disposal in 1946.

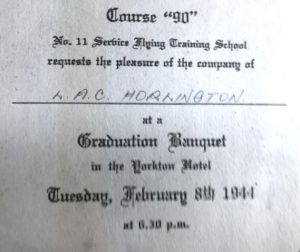

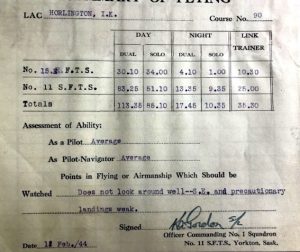

He completed the course and received his wings in February 1944, with a banquet to celebrate:

Although he may not have been completely thrilled with his school report:

‘Does not look around well’. Hmmm.

Now comes the puzzle. He returns to Blighty a fully-trained pilot with over 200 hours’ flying and …nothing happens. The war is at its height, but he does not go to advanced training and then an operational squadron. Instead he seems to cool his heels. The logbook shows him next going back to basics at an Elementary Flying Training School in Perth for a brief spell flying Tiger Moths in June 1944 to keep him current.

De Havilland Tiger Moth Trainers

Then another, much longer, gap before he finally reappears at the No. 4 School of Technical Training at St Athan in Wales in March 1945 on a Lancaster flight engineers’ course (he never mentioned this!). Historian of the RAF, Air Cdre Graham Pitchfork, who read this note, explains the reasons for the delay and then this Flight Engineer training:

“By the summer of 1944 , it was possible to see an end of the war in Europe and attention was turning to Japan. Bomber Command was starting to plan a bomber force (Tiger Force) for the Pacific to join the USAAF in attacks on Japan mainland. These operations would be at extreme range and it was decided that two pilots would be needed instead of a pilot and a flight engineer. Therefore, the second pilot in the crew had to be trained to carry out the flight engineer’s duties.These men were drawn at weekly intervals, in batches of approx 60, from the substantial pool holding at 7 PRC at Harrogate.The training was conducted at 4 SofTT at St Athan (the flight engineer’s training school) and the course lasted 17 weeks.The first group arrived at St Athan on 30 Aug 44 and they continued until late 1945. Needless to say, many pilots who had just received their wings were disappointed, but the alternative was to take up a ground trade, with inevitable demotion in line with ground tradesmen“.

AVRO Lancaster BVII (FE) of RAF Tiger Force – Pacific Theatre 1945.

This all fits. Tucked away on the last page of his main logbook, there is a delphic reference to 7 PRC Harrogate. This turns out to be a Personnel Reception Centre used for pilots returning from training courses in Canada before their onward postings. By 1944, there were more pilots available than places on operational squadrons (Bomber Command expansion was complete, the rate at which pilots were being killed had slowed a lot, and the Canadian flying schools were churning out large numbers by now). The ‘spare’ pilots were sent to 7 PRC to cool their heels. (Ivor never mentioned spending months hanging around in Harrogate!)

After his 17-week course at St Athan, Ivor continues the classic training pattern for a heavy bomber pilot. He moves on to the 1661 Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Winthorpe in Nottinghamshire where he flies 41 hours on Lancasters. Finally, on 3 July 1945 he joins 619 Squadron at Skellingthorpe in Lincolnshire (equipped with Lancasters). But with the war in Europe over, he gets only 7.40 flying hours as co-pilot before the squadron is disbanded on 17 July’.

Over the next few months, Ivor flows what Air Cdre Pitchfork described as ‘a typical end of war series of short duration appointments filling holes left by those who were being demobbed having joined before Ivor’. The first of these is No.3 Advanced Flying Unit at South Cerney in Gloucestershire. There he spends 6 weeks flying Airspeed Oxfords (similar to the Cranes he flew in Canada) before taking a one-week Beam Approach Training course at RAF Watchfield not far away in Oxfordshire. This taught him instrument flying and blind approaches (scary) and was part of the normal training for operational flying of multiengine aircraft. But he only has one opportunity to use these new skills. From 1-20 January 1946 he is co-pilot on an RAF Dakota flying to Delhi. It took 36 flying hours via Istres in Provence, Sardinia, Malta, Libya, Palestine, Iraq, Bahrain, Karachi and Jodhpur. Phew. He comes back as a passenger and never touches Dakotas again (I remember him saying that he didn’t like flying that aircraft). One hint that he did not enjoy his brief time on Lancasters and Dakotas is that there are no pictures.

Airspeed Oxfords – The RAF Station “taxis”

He must have been demobilised after this, because his next appearance is joining his beloved 607 Auxiliary Squadron at Ouston in June 1948 (members of the Auxiliary Air Force were part-timers but could be called up if needed in a crisis). This is where he got his hands on the Spitfire. He trained for this by flying two-seater Harvards and doing back-seat landings, which apparently gives the best approximation to the view from the Spitfire.

North American T6 Texan – known by the RAF & Commonwealth as the “Harvard”

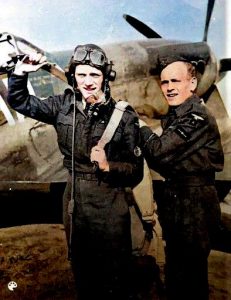

Here the pictures start again, suggesting that was enjoying himself once more. I like this pic because you can also see in the background the Spitfire XIVs with their five-blade propellers which he was in the process of converting to.

Ivor (2nd from left) amongst Harvard twin seat trainers & Spitfire Mk.XIV’s.

Back to serious business. After 3 months of intensive flying on Harvards 607 Squadron do a summer camp at Lubeck in northern Germany and while there hey presto he does his first solo in the Spitfire Mk XIV on 27 July. From then on it’s lots of:

On the wing of his Spitfire

And:

Ivor getting “strapped up” for his Supermarine Spitfire Mk. XIV

In 1949, the Squadron converted to the Spitfire XX, then in 1951 to Vampire 5s. Ivor first flew solo in the Vampire in April 1951, presumably his first experience of flying a jet. The Squadron complement was 10xVampire and 1x Meteor 7, the two-seater trainer variant. Ivor records his first flight as second pilot on this as being after his Vampire solo. (It seems pretty remarkable that the RAF let these part-time airmen loose on these jets with minimal conversion training from Spitfires). Although he did far more hours on Vampires than Spitfires in total, Ivor only left one pic of him in a Vampire:

Line up of De Havilland Vampire Mk V, jet fighters

The Squadron were called up to full-time service in July 1951 as the Korean War began, and spent three months preparing in case they were needed for combat flying. Lots of live firing and battle formation. In this period Ivor did his first solo on the Meteor.) Pitchfork comments ‘All auxiliary squadrons were called up at the time of the Korean War but were released after about four weeks.’

RAF Gloster Meteor Mk1 – the first Allied jet fighter came into service in July 1944.

With a return to normal conditions, they went back to part-time, but took their Vampires on some ambitious summer training camps: eg to the island of Sylt in the North Sea in 1953, Bruggen in 1954 and Gibraltar in 1955. The planned summer camp in Malta in 1956 was cancelled because of the Suez crisis, and they ended up at Aldegrove (Belfast) instead!

De Havilland Chipmunk twin seat Trainer

Ivor had completed over 1,000 hours with 607 when it and the whole Auxiliary Air force disbanded in 1957. In 1959, he resumed flying as a Flying Officer in the Volunteer Reserve (and could still have been called back to active duty until 1961). From then on it was Chipmunks, very like the aircraft he started on (the Cornell), flying air cadets on air experience flights from RAF Ouston in Northumberland. He finally hung up his goggles in December 1972.

“Following in Ivor’s footsteps”. Grand-daughter, Caroline tries out the pilot seat in a Harvard Trainer at Biggin Hill.

One final conundrum. Ivor often retold the tale set out in his attached note, about about the time when he shot himself down. Oddly, I can find no trace of it in his log books, which are otherwise meticulously kept. Make of that what you will!

Peter Ricketts – February 2021

Ivor Horlington

York

YO1 7LP

I was flying a Spitfire in the post-war service of the Royal Auxilliary Air Force one Sunday morning, concentrating hard on air-to-ground gunnery practice: this involved a series of tight circuits from about 1500 feet to dive on to and fire four cannon at targets which were set at 45 degrees to the vertical on the beach at Druridge Bay, Northumberland.

All went well for several passes, but after pulling away from one attack the engine began to belch forth lots of acrod and dense smoke, so I had to jettison the cockpit hood in order to stick my head out to one side to see where I was headed.

Eventually a most welcome sight appeared through the gloom around me in the shape of a runway at which I pointed the aircraft with some alacrity! The propeller ground to a shuddering halt on the way down, but I managed to land on terra firma in one piece – I suppose, in complete silence!

The eventual realisation was that I landed down-wind on the shortest and pot-holed runway of a disused and long-neglected airfield without incurring so much as a scratch on the Spitfire itself: but when the engine cowlings were later removed, the Merlin engine had welded into one solid mass of metal, due to severe over-heating.

The cause? A ricochet from a cannon shell had pierced the engine radiator intake under the belly of the aircraft, and all available engine coolant had been lost in just a few seconds.

I have yet to hear of anyone else who has shot himself down in a Spitfire – especially in peacetime!

Ivor.

Published: 2nd February 2021.

AFHG Edited & Presentation: Ian Reed

I’m wondering if the author of this post has access to Ivor’s flying logbooks? As well as being extremely interested in 607 Squadron, I would like to identify the Spitfire Ivor landed on the disused airfield, which I believe to be RAF Eshott.

Eshott trained Spitfire pilots during the war and Ivor may have the distinction of being the last Spitfire pilot who landed there.

Dear Jim,

Lord Ricketts tells me: “I was delighted to hear that Jim Corbett took an interest in Ivor’s flying stories …….the target practice was happening in Druridge Bay, and Eshott is a few miles inland from there, so I think Jim is dead right in his identification of the disused airfield. Lady Ricketts (Ivor’s daughter) cannot remember Ivor ever mentioning the name to her.

The curious thing is that there is no mention at all of the incident in Ivor’s meticulously kept logbooks. It must have happened between 1948 and April 1951 when the squadron converted to Vampires. In that time Ivor flew various Spitfire XVI and XX with codes in the RAN A/B/C/ series up to RAN/N. Then some coded LA B/C/G/H/K/M. It must have been one of those. Might maintenance or write-off records help?

Please pass this on to Jim with my best wishes.

Hi-As this incident occurred on a Sunday it would be possible to pick out the Spitfires flown on a Sunday from Ivor’s pilot’s flying log book so as to have a list of the aircraft serial numbers and then to request the RAF movement cards which would reveal damage so to identify the Spitfire in question therefore would this be possible to request this. Thanks,Philip Smith [Newcastle-Upon-Tyne]