The Beginnings of WWII – Nanjing 1937 – Lin Shi

Fragments of Remembrance – as one of the “Big 4” allies of WWII, China’s horrific war began much earlier.

The memorial to the 300,000 victims of the Nanjiin Massacre 1937

Where Memory Begins

The Second World War ended with the Japanese surrender in Tokyo on 2nd September 1945.

World War Two – the “Big 4” Allies – USA, Soviet Union, Britain & China

For the USA this had been 3 years & 9 months of fighting since December 1941, for the British Empire & Europe the war had taken 6 years from September 1939, but for China the war had begun as early as 1931 – the culmination of continuous Japanese subjugation on mainland China since the 19th century.

The story of Nanjiin (or Nanking in the European spelling) in December 1937 was one which horrified nations and sent shock-waves throughout the world. This new moral depth in 20th century warfare sent alarm bells ringing throughout the West. The appalling brutal atrocities at Nanjiin were of a different dimension and perversion than seen before and clearly gave notice as to how the coming warfare in the East would be of a totally different character.

Nanjiin in 1937

Once the flourishing capital of Chinese culture, on 13th December 1937, Nanjiin was consumed by six weeks of devastation, mass execution, rape, and wholesale murder in a frenzy of the most barbarous nature. In what has been described as the single worst atrocity of Word War 2, it claimed the lives of more than 300,000 men, women & children.

As a native of Nanjiin it is important to understand that the city’s memory endures not only in testimonies and photographs, but also in the silence carried across generations. To remember the Rape of Nanjing is not to dwell in bitterness, but to let history’s fragments remind us of the enduring value of maintaining and managing peace.

Recently, the film by The Nanjing Photo Studio has received wide acclaim across China for its sensitive portrayal of history. Yet, as someone born and raised in Nanjing, I long found myself hesitant to face the subject at its horrific core. The Nanjing massacre is not only a chapter in history books, it has always existed as a presence woven into the DNA memory of its people and the identity of the city itself.

Nanjiing today, capital of Jiangsu Province and situated by the Yangtse River. With over 2500 years of history and a former capital of the Ming Dynasty, today it is a thriving metropolis with a blend of ancient and modern.

A City of Layers

Nanjing, the former capital of ten imperial dynasties and later the capital city of the Republic of China, carries many layers of historic legacy-imperial grandeur, cultural refinement, and political turbulence. Its ancient walls and riverbanks have witnessed the rise and fall of kingdoms and governments alike.

Centuries of migration shaped a culture of openness and inclusivity in Nanjiin. Repeated wars forged a spirit of resilience; and for more than three hundred years during the Six Dynasties, the city stood as a flourishing center of literature, art, philosophy and religion-a period often regarded as a renaissance in Chinese cultural history. This deep heritage makes the wound of 1937 all the more profound, for it struck at a city whose identity had long been built upon endurance and creation.

Historical Background

In the 17th Century Russian expeditions had reached the Pacific Coast along the Aigun River border in Manchuria in Northern China, which at that time was governed by the Ming Dynasty. Several attempts by the expanding Russian Empire to annex the vast land north of the river by threat included posting thousands of troops on the border and numerous military incursions, which eventually led to the Governor ceding this vast territory under the Treaty of Aigun in 1858. Although rejected by the Imperial Chinese Ming government, it was eventually ratified on 14 November 1860 at the Convention of Pekin following the Second Opium War, this giving Russia control of both the vast northern territory and of the Pacific coastal area of Manchuria right up to the Korean border, including the island of Sakhalin, (over 900,000 km²) which exists today as the current boundary between China and Russia.

Fear of the increasing Russian “sphere of influence” in East Asia and Korea, Japan had obtained a lease from China to the Leodong Peninsula in 1898 and offered to recognize Russia’s dominance in Manchuria in exchange for Japan’s recognition of Korea as part of its “sphere of influence”. This was rejected by Russia, and Japan duly launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur on 9th February 1904. In May Japanese troops entered the Manchurian capital which was then at Mukden and under Russian control. The war ultimately ended in the humiliating defeat of the Russian Baltic fleet by the Imperial Japanese Navy at the Battle of Tshushima in May 1905 , following which Japan was granted new permissions in China and Korea and assumed control of the former Russian South Manchuria Railway, in effect acting as “rulers” over Manchuria.

The Russian battleship “Oleg” was only one year old when it took part in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905. Despite severe damage by the Japanese Navy it was the only ship of its class to survive the battle.

Meanwhile, with the huge differences between world cultural and industrial evolution and the resulting internal struggles, uprisings and attempts to revolutionise China, this eventually led to the overthrow of over 2000 years of Imperial Rule and the 267 year old, now feeble, Qinq Dynasty. The Republic of China was declared on 1st January 1912 and on 12th February 1912, the six year old Puyi, Imperial China’s last emperor, abdicated.

The Last Chinese Imperial Emperor – Puyi

This new Chinese republic soon began to re-assert its new authority and reclaim territories accessioned by other countries. Rebellion against Japanese interests in Manchuria increased whilst in the background the struggle to unify a fractured China continued.

By 1925 the Chinese Republic was ruled by the Kuomintang Party based in Nanjiing and lead by General Chiang Kai-chek.

Nanjiing prospered greatly at this time despite numerous isolated incidents with the Japanese occupiers in the north. This continued until 18th September 1931 when the “Manchurian Incident” changed everything.

Later photo of Chiang Kai-shek, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill at the Cairo Conference in November 1943, to discuss the Allied strategy against Japan.

The “Manchurian Incident”

A “false flag” attack, secretly undertaken by elements of the Japanese military, possibly without full consent of the Japanese government, occurred in Mukden (now Shenyang) on 18th September 1931. Explosives were placed safely away from the tracks on the Japanese controlled branch of the South Manchuria Railway but near enough to blame Chinese nationals. A major attack occurred the very next day where the Japanese used artillery in a surprise attack on the nearby Beidaying Barracks killing around 500 Chinese troops. The incident was a pretext for the full-scale invasion of all Manchuria by Japanese Imperial forces who then occupied the capital, Mukden. On September 21, Japanese reinforcements arrived from Korea, and the army began to expand throughout northern Manchuria.

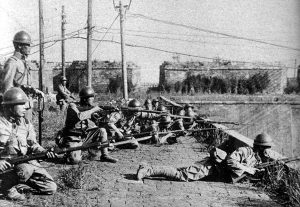

Japanese infantry in action at Mukden

China, already over burdened with internal struggles as well as a major flood disaster of the Yangtse River, appealed to the League of Nations, predecessor to the UN. The League of Nations sent a commission to investigate, headed by the 2nd Earl Lytton, which arrived in Shanghai on 14th January 1932. It reported back and on October 24th the League resolved that Japan should withdraw all troops by 16th November and refused to accept Manchuria as an independent state. At this stage the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong began to give its support to the republican government as it recognised the threat which now faced the whole of China. This was known as the Second Kuomintang – Communist Party Co-operation and began in December 1936.

Lytton Commission members of the League of Nations inspected the reportedly damaged South Manchurian Railway near Mukden in September 1931.

By 1st March 1933 Japan had resigned from the League of Nations and established the new state, renamed “Manchukuo”. Former emperor Puyi, now aged 28, was eventually installed assuming the title of Emperor of Manchukuo on 1st March 1934, a role he played until the World War’s end in 1945.

Former Chinese Emperor Puyi was re-installed as a “puppet” leader by the Japanese in Manchukuo in 1934.

By this time Japan was already aligning itself with the Axis powers of Germany and Italy and a continuous series of armed conflicts continued across China until July 1937 when full-scale war began, often seen as the real beginning of World War Two. The first major assault was the 3 month Battle of Shanghai ending in November, followed swiftly by the advance onto the Chinese capital Nanjiing by 50,000 Imperial Japanese soldiers. The attack began on 13 December 1937.

The Winter of 1937

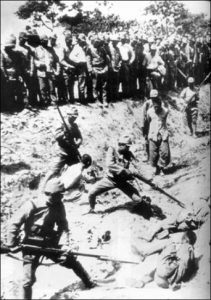

In that winter, Japanese troops occupied Nanjing. What followed was six weeks of devastation: more than 300,000 civilians and prisoners of war were murdered, tens of thousands of women were subjected to sexual violence, and entire neighborhoods were reduced to ashes.

Poorly armed and trained, the 90,000 Chinese troops defending the city surrendered to the modern equipped Japanese army. Shortly thereafter all 90,000 prisoners were murdered, followed by an encouraged rampage across the city killing every civilian in their path.

The details of the atrocities are too numerous and obscene to describe in detail, but more than three hundred thousand babies, children, women and men of all ages were abused, bayoneted, burned or buried alive, drowned, decapitated en masse and murdered, often in killing competitions between army units.

I did not want to show the graphic images in detail here but for historical research purposes original photographs of the atrocity can be found on the internet, although I must warn that they are horrific. Later research has suggested some photographs were not dated and may be from other incidents or indeed altered, but the basic fact is that atrocities of unimaginable ferocity against men women and children of every age took place in Nanjiin in that fateful December of 1937.

This was not an isolated tragedy, but part of the broader pattern of aggression during Japan’s invasion of China – a campaign that formed one of the largest and bloodiest theaters of the Second World War. The Nanjing Massacre stands as the one of the darkest moments of twentieth-century warfare, and its significance extends far beyond national boundaries. It belongs to the shared history of humanity, demanding remembrance and recognition alongside other atrocities of the war.

Fragments Returned

This history is preserved not only in survivors’ testimonies and foreign accounts, but also through visual evidence-some brought back to light thanks to remarkable acts of goodwill. In February, Frenchman Marcus Detrez donated 618 wartime photographs taken by his grandfather to a Shanghai memorial hall. Across the ocean, American Evan Kail donated a photo album documenting Japanese atrocities to the Chinese Consulate in Chicago. These fragments of memory, returned decades later, remind us that the past continues to find its way back into the present.

Through Cinema’s Lens

The memory of Nanjing has also been revisited through cinema, where art becomes a vessel for grappling with the weight of history. Zhang Yimou’s “The Flowers of War” and Lu Chuan’s “City of Life and Death” both sought to depict not only the horror of destruction but also the resilience of human dignity.

Through images of ordinary lives caught in extraordinary violence, these films translate historical tragedy into a universal language of empathy. They remind us that the cost of war is not confined to statistics, but to broken families, fragile hopes, and the enduring value of peace.

Memory as Conscience

“As both a curator and a native of Nanjing, I share these memories not to assign blame or stir resentment, but simply to let remembrance speak. To recall the Nanjing Massacre is not a matter of politics, but of conscience.

When I was a student, our teachers would lead us to the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall. I still recall the haunting photographs, the fragile documents, and even the bones unearthed from the earth – impressions so stark that they became part of my earliest understanding of history. These memories, carried with me far from home, live on as a quiet weight within my body. Each time I attend a commemorative event abroad, that weight resurfaces, stirring both grief and longing for my hometown. Perhaps this is not mine alone, but part of a larger, unspoken inheritance – what might be called a collective trauma that lingers long after war has ended”.

When Silence Speaks

To remember is to honor the dignity of those who suffered and to acknowledge the cost borne by civilians in times of war. Commemoration is not about reopening wounds; it is about affirming our shared humanity. Art and cultural expression can carry these memories across borders, creating spaces for empathy where words may falter.

To remember Nanjing is to keep faith with the past, and to allow its silence to speak across generations.

Lin Shi

Paris 2025

Lin Shi was born in Nanjiin, China. She is a former museum director and curator who now lives in Paris where she works as a professional art consultant & historian. She is also a member of the management team of the Allied Forces Heritage Group/Groupe du Patrimoine des Forces Alliées.

Edited & produced by Ian Reed AFHG/GPFA – November 2025.

Hi Lin,

Many thanks for this facinating piece of history.

The Japanese at that time right up until the end of WW2 were ruthless, and barbaric. They have a lot to answer for, for the war crimes they committed against civilians and service people.

I know of british servicemen who were prisonners of the Japanese and listening to their stories of what they witnessed and experienced is incredible. My Godfather was taken prisoner by the Japanese and suffered with extremes of torture. The RSM of the Cambridge Regiment at that time in Singapore was also taken prisoner along with members of the Regiment. He and his men suffered greatly. He told me that he would never forgive and would never speak to a Japanese person as long as he lived.

Dear Richard,

Thank you very much for sharing this powerful and painful history. The experiences of British servicemen held by the Japanese during the war are deeply harrowing, and the trauma they carried throughout their lives speaks to the immense brutality of that period. I truly appreciate you bringing these personal stories into the conversation — they remind us that the suffering extended across nations, affecting countless families. Remembering these histories with honesty and compassion is essential, and I’m grateful that you took the time to reflect on the article through the lens of your own lived connections.

Lin, this is a magnificent account of a horrific and harrowing period in China’s history. The dignity of your prose respects the memory of the tortured souls. Your delineation of the events leading up to the terrible events in Nanking is very detailed and helpful to those of us who have up until now perhaps held only an outline understanding. Understandably impassioned, you provide a heartfelt insight into the impact on subsequent generations of the collective memory of such horror. A superb and important piece of writing.

Sheryl, thank you sincerely for your generous words. I’m grateful that the piece offered clarity on a history often known only in outline. I felt compelled to write it because each time I attend a commemorative event abroad, that familiar weight returns — a mix of grief and a deep longing for my hometown. Your recognition of the dignity owed to the victims, and of the lasting impact carried through cultures and generations, means a great deal! I’m appreciated your engagement with this difficult subject so thoughtfully.

Thanks

Lin, this most poignant piece of writing bears witness to the horrors which, like so many, give a profoundly unbearable insight into the very darkest side of humanity. I was ashamedly unfamiliar with the details and background. The eloquence of your writing is such that our understanding is not only marked by an indelible sense of tragedy, but also by the utter certainty that it is unthinkable to remain ignorant of the history that shapes us. To teach it, and learn from it is essential, and perhaps the most dignified form of gratitude and honour we can convey.

Thank you.

It was a joy to meet you on Saturday, standing beside you and many others, in remembrance and with utter humility.

Thank you, Chloe, for taking the time to read the article and for your thoughtful comment.

Remembering Nanjing within the broader context of WWII is not only about recounting history — it is also about acknowledging the shared human stories that connect our pasts. I truly appreciate your sensitivity toward this chapter of history.

It’s also great to know you, and have you to engage our remembrance events.