“L for Love” Part I – The Man Who Fell from the Sky – – André Guédez

80 years ago, an extraordinary but true story about the crew of a special aircraft, which continues to this day.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Approaching Christmas 1944 and the Allies had made great advances across France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland. The huge logistical problems of supplying the troops 340 miles (540km) ahead from the landing beaches in Normandy had at last been overcome by the capture and eventual opening up of the port of Antwerp by the British 21st Army Group on 29th November. But bad weather and heavy snow falls across the front had brought the advances almost to a stop and by mid December, as the Allies began to approach the borders of Germany, the intelligence provided by the French and Belgian Resistance which had been so valuable before, was almost non existent now. Poor visibility had also prevented effective aerial reconnaissance, but the Allies were reassured in the belief that they faced a beaten German Army with inferior troops and few effective weapons.

“The War will be over by Christmas“ was on everyone’s lips.

So it was, that on 16th December, the Allies were taken completely by surprise when about 450,000 Germans troops supported by 1,500 tanks, 2,600 pieces of artillery 1,600 anti-tank guns and over 1,000 aircraft suddenly emerged through the almost impenetrably dense Ardennes Forests in Belgium and Luxembourg and thrust directly into the thinly held centre of the US 12th Army Group. Their aim, to split the British and US armies and prevent the use of the port of Antwerp by the Allies.

The Ardennes Offensive “Battle of the Bulge” – December 1944

With the inability to use their superior air power due to bad weather, the Allies were taken off-guard and in the freezing conditions the situation quickly deteriorated. The Ardennes had been thought to be impassable and no one had imagined the huge numbers of men and machinery could have been hidden in its interior. The German tanks sped across the frontier and made large advances into the centre of the Americian 12th Army Group line. By the 19th December the US 1st and 9th Armies had been put under the command of Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21st Army Group with General Bradley commanding the remaining 3rd US Army to the south of the “bulge”. In addition the US IX and XXIX Tactical Air Commands were put under the operational control of the British Second Tactical Air Force commanded by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham.

Then on the evening of Christmas Eve the skies cleared…….

L for Love

24 year old André Guédez was a mid-upper gunner of Handley Page Halifax bomber “L” for Love, of No.347 “Tunisie” Squadron flying with Royal Air Force. “Tunisie” was one of two French Air Force squadrons flying with the Royal Air Force and André, with his 6 other crew members, were heading out for a well-earned evening with their girlfriends in York – it was after all “Christmas Eve”!

As they readied themselves for the night’s festivities the new orders arrived – “all leave cancelled“. Suddenly their lives changed and, unable to make their excuses to their girls because of the strict security, they began the detailed preparations for an urgent mission over Germany to try to help support the Allied defence against the surprise German attacks. Their mission, to attack the munitions factories in the Ruhr Valley which were supplying the German advances into the Ardennes battlefront, later known as the “Battle of the Bulge”.

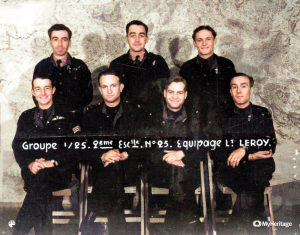

Top row from left to right: Sergeant André Guédez mid upper gunner; Sergeant François Duran, Flight Engineer; Sergeant Yves Even, rear gunner. First row from left to right: Sergeant Louis Baillon, pilot; Flying Officer Jacques Leroy Navigator and Captain; Pilot Officer Pierre Gautheret, bomb aimer & Flight Sergeant Henri Granier, radio operator.

Their huge, lumbering, Halifax 4-engined bomber, “L for Love” took off at 11:31am on Christmas Eve 1944 with 8 other aircraft of “Tunisie” squadrons, joined with Halifax’s from No.102 Squadron. After almost 3 hours flying in the freezing, foggy conditions they were above Essen Mülheim, location of the huge Krupps armaments factory. Almost immediately “L for Love” was hit by anti aircraft fire in the notoriously highly defended Ruhr Valley, known as “Happy Valley” by the airmen. Probably the most heavily defended area ever created with thousands of defensive guns, some even radio controlled.

German anti – aircraft defences – guns, searchlights and night fighters

As André recalls:

“The Ruhr sky was, at that time, the most explosive place in the world. The Germans had more than 30,000 anti aircraft batteries around their factories and towns. It was the industrial heart of the 3rd Reich, even though it was tottering at that time. On each incursion, especially at night, we were floodlit like in a parade, with continuous fire from anti-aircraft guns. We knew one in two aircraft might not come back, and until that day, I had been lucky”.

André remembers that the first shell hit the inner port engine. “It was quickly on fire, but we still had three engines”.

RAF Bomber Command sustained huge losses of aircraft and airmen

The 26 year old pilot Flight Sergeant Louis Baillon, called over the radio if everyone was OK and whether they should carry on or return with the damaged plane to base. The replies were unanimous “keep going!”

The problem was that with only 3 engines they had slowed down considerably and by the time they reached their target the anti-aircraft guns had been able to sharply focus. The Halifax released its bombs over the target around 2:30 p.m. but was soon hit again. André recounts, “The second shell cut the aircraft controls. This time, it was lost.”

Grab a parachute – almost!

“The pilot and the captain* gave us the order to jump. I then disconnected the heating of my suit and my oxygen mask. At 6000 m high, the temperature was –50 degrees C and the oxygen is very rare. In a few minutes I knew I would be unconscious.”

Life as a member of operational aircrew was to live knowing they had just a 50% chance of survival and could be dead at any time or any day. In this stressful situation airmen use all sorts of lucky (or unlucky) charms or habits to help calm the nerves. In his signature gesture of bravado, André would throw his parachute into the aeroplane fuselage rather than the appropriate storage rack, believing that if he had it close by, he was more likely to need it! Now, as “L for Love” became a burning inferno and with just seconds before the high octane petrol in the wing fuel tanks caught fire, he discovered with horror a huge hole in the fuselage and thought his precious parachute has been blown away. A frantic search and he thankfully soon found it and began to fit the cumbersome equipment whilst in the jolting dark confines of an aircraft on fire.

The escape hatch below the pilot had been opened and he sat with his legs dangling into the cold air outside, preparing to jump, and had just enough time to fasten the parachute before he began to lose consciousness – just at that moment another explosion rocked the aircraft with a direct hit on another engine and the force of the blast through the open hatch threw him backwards and he lost consciousness.

“I was scared, paralysed by the cold and the lack of oxygen. The Flight Engineer (François Durand) who was behind me pushed me out of the hatch into the open air. I must have opened my parachute instinctively, because the next second I was unconscious and don’t remember anything!”

He fell the 18,000’ feet (5500 m) to earth amidst all the screaming engines, guns firing and explosions and remembers nothing until he regained consciousness. Still in his flying kit, he was lying on a desk in an office with an injured face and back. When he awoke he noticed the clock – the time was 16:00.

“I woke up an hour and a half later. The bombing was at 2:30 p.m., I woke up at 4:00 p.m. I was sitting on a cot in an office where I could hear typing, I think there were young women typing“? He was aware that people around him were speaking German, so André knew he was a prisoner. But he had survived.

“Opening my eyes, I saw kids with noses pasted to a window looking at me. An old German soldier, a poor chap who had been called-up, was looking after me.”

Incredibly André’s first thoughts were for his English girlfriend Joan, waiting for him in York on Christmas Eve and how he could let her know he wouldn’t be able to meet her in town that night: “We really were in clover at the station (RAF Elvington), cherished and pampered, and I said to myself the dream was over and there would be no Christmas that night by the fireplace.”

This was not a good time to be a captured airman. “At that time the Germans were furious against the Allied airmen. The terrible bombings in Dresden, which caused the death of 45,000 people, were considered war crimes”.

They threw him into a civilian prison on Christmas Eve and later he found his Flight Engineer, Sgt. François Duran, who had survived as well. “We were happy to see each other again. The day after, we were sent to an interrogation centre. We had a really hard time when a Wehrmacht Officer, threatened us”. As France was “German Occupied territory”, French airmen & soldiers fighting with the Allies were considered as traitors and open to capital punishment.

To add to his worries, André learnt afterwards that they were the only two survivors out of his seven crew members. Three others were shot as they parachuted to Earth and the pilot and navigator who had stayed at their posts and battled to hold the plane steady whilst the other 5 crew jumped, were killed when the fire reached the fuel tanks, exploded and crashed in the outskirts of Düsseldorf at Wersten im Brücherbach.

(When news of the loss of “L for Love” got back to their base in Britain, the French Air Force ground crew refused to re-name the squadron’s replacement Halifax as “L for Love”, as was the custom. This had been the 5th Halifax with that name lost in just 18 months – there was no point in tempting fate once more).

Prisoner in Germany.

André spent four and a half months as a prisoner in Germany and during that time André remembers being marched through the devastated German towns and cities.

Nüremburg in 1945

Two or three days after the raid, André and François were transferred to a camp near Düsseldorf for fifteen days, whereupon they were again transferred and spent the next three months at a Prisoner of War transit camp near Frankfurt. Eventually they were again transferred by train from the Dulag Luft (Durchgangslager der Luftwaffe) to Stalag Luft 7a (for air force prisoners) near Münich, where they arrived in early April 1945.

En route, twelve USAAF Thunderbolt fighters attacked the train which was also carrying ammunition wagons, so André and François with two other prisoners and German guards ran for cover and hid in a cellar at a railway station, but were very worried as flames began reaching the cellar. They escaped from the cellar but shortly after, another attack began and André took refuge alone in a house where someone was treating a wounded man. Shocked by what he had experienced he was uncertain what to do so he gave his only possession, a chocolate bar, to the German people and left the house.

André explains: “When I was a prisoner, we walked a lot. At the end of the war, the Germans had decided to take us, I don’t quite know where? We walked a long way for a long time, and I happened to cross, with my prisoner comrades, the city of Nüremberg which had just been bombed. There I saw women who must have been looking for their children. There were bodies everywhere, it made me feel terribly emotional, and not only me. And whereas we would regularly ask if we could stop each hour to rest, we rushed across the city, so shocked by what we had seen.

That is why, afterwards, I thought that there’s no one more anti war than those who fought in it.”

We were eventually sent to a camp near Münich. Hitler had the crazy idea of setting up a prisoner of war camp in the Bavarian Alps. The Americans released us on 29th April 1945.”

André Guédez.

Stalag Luft VIIa at Moosburg 35km north east of Munich

For 67 years, André and François Duran (the only other survivor) telephoned each other every 24th December to remember the five close friends they had lost that tragic night. The day which began filled with hope and happiness for Christmas but had ended just a few hours later with most of his crew dead. François died in 2009.

After the war André continued in the French Air Force eventually becoming a Colonel.

André with his daughter Geneviève and his grandson Thomas at Mérignac air base in September 2008.

French bomber crew veterans with Halifax Mk III replica, “Friday 13th” in French colours – May 2009. L to R: André Guédez; Lucien Mallia; Pierre Patalano; Hervé Vigny and Louis Hervelin

In 2008 his daughter Geneviève Monneris helped by his grandson Thomas Lesgoirres, made the film “De Lourds Souvenirs” (Heavy Memories), a play on words alluding to “Groupes Lourds” referring to the two French Heavy Bomber Squadrons: 346 “Guyenne” and 347 “Tunisie”. The documentary about André’s wartime experiences won the prestigious IWM London Film Festival in 2012.

André died in July 2017, he was 97.

©AFHG 2020

De Lourds Souvenirs “Heavy Memories”…………click in the centre to see the film

* Note: in French crewed aircraft at that time the senior officer was not necessarily the pilot. In the case of L for Love, the Captain was Flying Officer Jacques Leroy, Navigator.

LATEST: remains of Halifax “L for Love” discovered in Wersten, Düsseldorf – January 2019 – see “L for Love” Part II

Click here: https://afheritage.org/example-post