Women of the Royal Navy – Geneviève Moulard

From her latest book, examples of the often overlooked but strategically vital roles played by the “Wrens” in wartime

In extracts from her latest book Geneviève Moulard revisits a little-known area (particularly in France) of the part British women played during the two wars. In these two short extracts from her new book “Les Femmes de la Royal Navy“, with a foreword by the Princess Royal, she underlines the value of British womens’ service by recalling the sacrifice of their youth, their attachment to their country and the values of courage and heroism inspired from glories past by the likes of Admiral Lord Nelson.

HRH Anne, The Princess Royal , Admiral and

Chief Commandant for Women in the Royal Navy

Introduction

As early as 1917, during WW1, the “Wrens” were seen on various fronts in Britain and abroad.

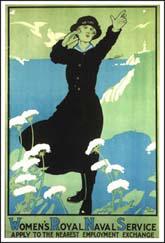

During the two world wars, one hundred thousand women combatants of the Royal Navy, both officers and crew, played a leading role in supporting the men in the vital war effort demanded by Churchill. Some 300 of them lost their lives in German submarine attacks and others experienced dramatic moments before being rescued. In 1917 and 1939, recruitment posters advertised, “Join the Wrens – free a man for the fleet” and their slogan was “Never at Sea ».

Enrolled in the WRNS or Women’s Royal Naval Service Auxiliary of the Royal Navy, the Wrens took the place of the men sent to the warships and participated in combat in all sorts of ways, in dozens of different, sometimes highly technical, occupations. Finally, after working on the organization of D-Day, a few lucky women were able to land on the continent through Normandy and make their way to Paris and Germany to help denazify Europe.

According to their skills, from the outbreak of WW2, they were drafted to “Station Y’s” to intercept German signals along the British coasts. At “Station X”, Bletchley Park,(Government Code and Cypher School), they worked together with the code-breakers striving to decipher the Enigma and Lorenz German cypher machines and in the central admiralty controlling allied shipping. Wrens also operated on coastal naval bases, (which carry HMS ships’ names), and as “cockswains” on small boats forwarding navigation orders to ships at harbour or, as “mailboat Wrens” delivering ships’ mail. Many worked under exceptional circumstances serving in areas of immediate targetted danger, especially at ports subjected to aerial bombardment, aboard troop ships or at various British Naval Headquarters abroad. Many lost their lives in the world’s oceans from enemy submarine attack or experienced exceptional hardship in order to survive a stricken ship before eventual rescue.

At Southwick House, Portsmouth, Wrens played a major role in the administration and organisation of the “ D-Day Landings” and afterwards some “lucky ones” managed to get to Europe via Normandy. As the war fronts evolved, they moved forward to the Paris area and eventually to Germany in order to take part in the Liberation of Europe.

WRNS Recruitment Poster

These “fighting women”, reached a peak of 75,000 by 1944 and experienced cheerful days, but also tragedy. They held high the esteem and pride of the “Senior” Service, had care-free days and good companionship, worked alongside famous European figures and, for some, the encounter with the man who was to change their lives for ever.

With original testimonies, “Les femmes de la Royal Navy” recalls the value of the womens’naval service and highlights the sacrifice of their youth. It enables us to understand the strong attachment to their island nation as well as the values of courage and heroism embodied by Admiral Horatio Nelson. It also enhances the major role of the sea to the island of Great Britain and its maritime superiority (a favourite image in Britain) as well as the historic role of the Royal Navy.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson, killed at the Battle of Trafalgar 21st October 1805

This unsung, almost forgotten story of British women in history is, for the French reader, a “first” as a Wrens’ history has probably never been published in France before. It is an example of a very heroic period and expands upon the wider effort delivered by British women at war which also serves as a tribute paid to all these proud and duty-bound women in the protection of their island, who supported their country through an unwavering commitment.

Anti aircraft gun maintenance aboard ship

The story of the Wrens is an example of the need for the expansion of a women’s service within a military sphere and the impact they had on an ancient male dominated institution, and emphasizes the general increasing socio-cultural acceptance of women reaching roles which was hitherto unthought of. Their remarkable feats emboldened younger generations to become equal to men in the Royal Navy. Today, in the 21st century, they have proved they could finally attain every level, right up to commanding a warship or performing all the responsibilities aboard a modern warship and are the logical development of a process which began more than one hundred years ago.

Two stories:

1. The sinking of the Empress of Canada, South Atlantic, 1943

RMS Empress of Canada, (21,517-tonnes, 653 ft/199m), built in Glasgow UK for the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company based in Vancouver.

The U-Boats were unleashed in early 1943 and did not spare British and Allied ships. At the instigation of Admiral Dönitz, who had just taken over the Kriegsmarine, other tragedies at sea would unfortunately remain engraved in the Wrens’ memories, in particular that of the troop-ship RMS Empress of Canada on 14 March 1943. When Singapore fell a year earlier, the first Wrens to be evacuated to Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) had to leave the city following air attacks. They were divided into three groups for the return to the UK. The first group, to be granted leave after two years overseas, was on board the Empress of Canada.

The ship carrying troops back to England was considered the largest troopship in the world. As she travelled at 28 knots, a speed thought fast enough not to be hit, she was not escorted. On board for the Royal Navy, there were six Chief Petty Officer wireless telegraphers, 30 officers and 60 sailors. Also present were Royal Air Force personnel, several hundred refugees, 300 Italian prisoners of war accompanied by one of their officers (who had given their word not to attempt to escape), and 200 French, Greek and Polish refugees. Three days after leaving Durban, a Greek stowaway, the wife of a Royal Air Force sergeant, was discovered in a lifeboat. But the journey continued optimistically: “Many times the ship was almost hit by torpedoes,” says Chief Wren Freda Bonner, “but our speed protected us. The journey continued peacefully around the Equator. Occasionally we came across upturned boats and the wrecks of torpedoed ships, but we were confident. We were going so fast that nothing could happen to us“!

A beautiful sunny day began on this Saturday in March in the tropics of the South Atlantic, west of Africa. During the evening, Freda Bonner was chatting on the deck of the Empress of Canada with Lieutenant-Commander Forman, one of the few Japanese interpreters in the service, who had not been home for six years. Returning to her cabin, Freda suddenly heard the thud of a torpedo and everything was suddenly plunged into darkness. A few minutes later, a second torpedo hit the ship. There was no sound or light alarm because the warning system is out of order and she heard a tumble down the stairs outside and then there is silence. She put on her coat and life jacket. As she left the cabin, she decided to take her money with her but changed her mind. No, she won’t need it, she thought, but she took some cigarettes anyway. She explains: “At 11 p.m. on 13 March, we felt the ship vibrate. The engines were idling. Then we heard a thud. We realised that the ship had been torpedoed”. She recalled a detail in the Geneva Convention on International Humanitarian Law, ordering submarines of all nations to wait 20 minutes before firing the final torpedo so that passengers and crew could leave the ship.

Torpedoed and sunk on 13 March 1943 – approximately 400 miles (640 km) south of Cape Palmas off the coast of Africa.

Suddenly, the sea opened up and a black monster burst out: it was the Italian submarine, the Leonardo da Vinci. The commander followed the rules of the Geneva Convention and then resumed the attack. When the Wrens find the lifeboats, they find that the one assigned to them is difficult to access and some are out of order. Meanwhile, Royal Navy officers dropped rafts and floats onto the water and ropes to lower the refugees and Italian prisoners of war. Passengers flocked to the boats and many burned the palms of their hands as they slide down the ropes. This is the price to pay to stay alive. Some simply jumped into the water.

Freda continues: “As we were moving away from the sinking ship, the Italian submarine came back and fired. The captain of the ship then ordered the last boat to move into position. At that moment, he lined up the lifeboat carrying the only Italian officer on board. The latter shouted to be recognised by the submarine’s crew and they were then extracted. Once on board, the submarine he even jumped for joy when the submarine pulled away and his crew had time to take photos of the survivors”.

Italian Navy Submarine – “Leonardo da Vinci“

A few hours later, the Empress of Canada capsized with a deafening noise and sank immediately. Survivors were in boats or floating in the sea. The six Wrens, wearing life belts, then imagined another danger in the distance: marine predators (barracudas). They tried to save face as the exhausted ship’s doctor finally sank into the depths. “I heard that noise again every night and it didn’t leave me for a year. It was a long night, people were calling for help, then dawn came,” she added.

After two days, the survivors were spotted on the surface of the water by an RAF Sunderland flying boat. The Wrens now knew that their prayers have been answered. All around them, they saw rafts with red sails and floats and survivors who had survived the night in their life jackets.

Finally, as the sun set on the evening of the fourth day, Freda and her comrades saw the destroyer HMS Boreas in the distance. Its commander was well aware of the risks of the rescue manoeuvre as U-Boats were known to lie in ambush, waiting for the rescue craft after a ship has been sunk.

Royal Navy Destroyer HMS Boreas

The Boreas approached and stopped near the rafts and boats to pick up survivors. Freda begins to lose hope as her lifeboat takes a long time to reach them. Finally, their turn comes. Sailors clinging to nets alongside the ship hoisted them aboard and handed them over to other personnel on deck. The manoeuvre is difficult because every movement puts them in danger.

Chief Wren Lillie Gadd, who had been alone in a dinghy with 40 sailors, was one of survivors recovered by the destroyer. As if to remind them of their ordeal, the young women remember seeing only empty life-boats, floats and life jackets that would eventually sink. She had been saved, along with the ten other women refugees from the Empress of Canada, but the rescue still left over a thousand missing. Two days later, the six Wrens and the ten passengers arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, a former British colony. However, by then 200 men were still missing, but thanks to the naval officers who did their duty until the last moment and risked their lives, the losses were limited.

Freda Bonner, who took part in the rescue, was praised for her exemplary conduct and returned home to Britain on the RMS Mauretania. Once in Britain she had to change trains several times and at one railway station, she asked someone about the route she should take. The passenger replied with aplomb: “Be happy just to travel! Don’t you know we are at war?”

Around the same time, intercepted messages and direction finding enabled the position of the submarine Leonardo da Vinci to be pinpointed, which was finally sunk on 22nd May 1943 by the destroyer HMS Active and the frigate HMS Ness, off the Bay of Biscay. The sinking of the Empress of Canada was the second greatest tragedy of the Wrens at sea after that of the SS Aguila on 19th August 1941, when 142 people were lost including 21 Wrens.

2. D-Day, a “Wren” at the heart of a secret

The last surviving member of the D-Day Plotters team was interviewed by the author and celebrated her 102nd birthday in 2021.

In her post-war diary, the young Wren, Beaujolois Cavendish, looked back on the years during which she contributed to the success of Operation Overlord amidst the greatest secrecy, for her country, for France and for the Allies. Beaujolois joined the WRNS at the age of 23 after marrying an officer, who left just one week later for overseas duties, and lived as a Plotter in one of the hundred rooms that made up Fort Southwick – one of the forts on Portsdown Hill, overlooking the naval base of Portsmouth, Hampshire.

Fort Southwick, Portsmouth, Hampshire

She remembered its labyrinth of tunnels, spread over an area no larger than 100 by 50 metres. The three kilometres underground had been dug 30 metres deep into the chalky soil and the structure was one of five Victorian forts built in the 19th century to protect England from French invasion. The fort with its underground tunnels was a strategic centre for Operation Overlord and it still remains today.

Legend has it that it is haunted by the ghost of a young French prisoner killed there during the Napoleonic Wars. One legend even claims that the holes in the walls of his cell were caused by musket balls and that his mother’s cries can still be heard on the ramparts looking for him.

In 1944 Fort Southwick housed the Portsmouth Commander-in-Chief’s bomb-proof Headquarters, which included a control centre for naval operations and had a staff of 140 officers and 480 crew. The tunnels have several passages leading to offices where, under artificial light and ventilation, teletype operators, coders, switchboard operators and cipher officers worked. The scene was set in the basement, and 179 steps have to be climbed to access it before going to or from work.

Access steps to Fort Southwick underground bunkers

(Fortress Study Group)

In the late spring of 1944 she was a WRNS Team Leader and had to keep “the Plot” updated (a large scale map of the seas around Britain showing all shipping movement) with the small coloured wooden models, showing in real time the situation of all the ships operating from Portsmouth and Southampton to the French coast. When she became a Leading Wren, she had the honour of sewing gold brass buttons onto her jacket, replacing the old black buttons typical of the Ordinary Wren rank. Then, promoted to Petty Officer, she was instructed not to take her meals with the Ordinary Wrens, but instead in a more comfortable mess reserved for the officers, with a radio and a library.

She appreciated the improved living conditions but regretted not being able to see her friends, and under the command of Commander Tim Taylor, she then led a team of fourteen Wrens and nine WAAFs. The night watches were now more interesting as they learnt a lot about the German E-Boats that left the French coast at night to lay mines in the Channel. To counter them, fast patrol boats were alerted from the “Y Stations” and given the position and speed of the enemy ships. When an echo appeared on the Plot map, the letter U for ‘Unknown’ was displayed to indicate an unidentified group and the exact time was noted. After three sightings and three new positions, the speed at which it is moving and whether it is a destroyer or a landing craft can be deduced.

Tunnels at Fort Southwick, Portsmouth

At the beginning of June, the main Plot Map was suddenly enlarged to approximately 2.50 metres by 3.50 metres. The south coast of England and the French coast can be seen on it. In the meantime, the night watch was increased to eight Wrens commanded by a WRNS officer. As radar technology evolved, the coverage of the hostile area was more efficient and of better quality. A young woman remained in constant telephone contact with the Y Stations, so that in the event of an emergency, the situation could be presented on the Plot in almost real-time. As Beaujolois was the only woman who enjoyed this work, she was sometimes asked to do the same on the officers’ maps, and one morning in May 1944 after she had worked there for eighteen months her commander showed her a chart to copy. It was the final detailed plan of the Operation Overlord – the allied invasion of Europe.

As the only person in the team who was not a Commissioned Officer, she was extremely flattered to be shown this highly secret information. Keeping absolutely secrecy, the other Wren in the team who was an Officer, was outraged that a Wren of lower rank could have been entrusted with such a secret. Later, Beaujolois learned from her former commander that she was just one of only nine people who had access to the invasion plans and that she was the eighth. Nevertheless, in her heart, she cannot help but thank her fellow Wrens who never wanted to work on the Plot.

Royal Navy Plotting Room

As the planned date approached, the pace of the work suddenly quickened. Now, in addition to the routine work on the movement of warships, Beaujolois concentrated on the landing craft. She saw enigmatic messages but understood that they were convoys escorted by ships, tugs and concrete constructions that she thought ‘strange’. All this remained a mystery to her until she discovered the existence of the famous floating Mulberry Harbours after D-Day. Meanwhile, above the Plot-Map, hands waved every 30 minutes to insert new information. When an ‘interesting’ situation arose, (as the Royal Navy called it), the Plot was flooded with light from the flashes of cameras, which allowed a much more effective analysis. The cameras shot from above and below, like in a film, with close-ups and fade-ins. Everywhere, there were the sounds of engines and the murmur of voices that were speaking to all parts of the UK.

In the Plot Room, the map of England was covered with a translucent Plexiglas film. It placed a grid over the map divided into small squares where the positions of the ships were plotted with a six-digit reference number. Beaujolois and the Wrens, who were at the end of the chain, received information by telephone, recorded from the radar screens of four Y Stations along the coast. Convoys were listed according to their direction with a number like: A7 if it is heading to Plymouth, A8 is a destroyer heading up the Channel and so on. Other personnel, informed of ship movements by the code breaking Cipher Room can also warn Plymouth or Dover.

On 4 June 1944, faced with this fantastic spectacle, Beaujolois wrote in her diary: “The headquarters of Combined Headquarters, which coordinated the first waves of assault on the Normandy beaches, are 30 metres below the ground. They are remarkably well hidden. They have miles of well-ventilated corridors with daylight lighting. There are representatives of the Royal Air Force, the Royal Navy, Canadians and Americans in contact by radio, tele-printer or telephone.

1944 – Fort Southwick Telephone switchboard, operated by women from sections within the British Army, RAF and Royal Navy.

They work on diagrams, typewriters, encryption systems and file the results in cabinets. In a few minutes, the Wrens in the switchboard make hundreds of phone calls. In another bay, the teletypewriters are in a frenzy. All the messages sent by the Wrens and the sailors are sent to the ships at sea by powerful transmitters to follow the operation in progress. It’s like a movie,” she said.

Beaujolois admired a gleaming metal generator and the whirring dynamos. She heard voices talking from all corners of England, carried by the submarine cable that is pulled across the Channel to the beaches of Normandy, to the ships at sea, to the men standing guard and the pilots waiting for the scramble, the signal to jump into their Spitfires. The green light for the operation would be given from these tunnels of light to the ships already at sea, to the men who had been waiting for many days in the assembly areas and to the pilots on alert at the foot of their aircraft. A senior officer even confided to Beaujolois that the communications network could be extended across Germany to the junction with Stalin’s armies. But the communications could not be tested before “Zero Hour” for security reasons, as radio silence was the rule and the time for landing was approaching. In this “room of secrets”, as Beaujolois calls it, everyone waited in great suspense.

Suddenly the tension was reduced when a postponement of “Zero Hour” was announced because of unfavourable weather at the beginning of June. After some procrastination, the decision was taken to wait a day as the weather forecast for the following day seemed better? The first wave of barges, each carrying around thirty men, were then called back to port, along with their escort ships. That night, however, a convoy was still heading for France and it seemed that it had not understood the order to withdraw. But, finally it turned back.

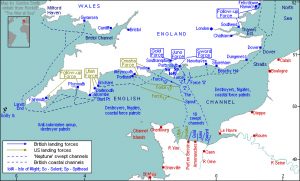

Royal Navy maritime management of the invasion forces – June 1944

Looking at the map, the Wrens were relieved to see that the whole fleet was now returning northwards. “This is an incredible moment,” thought Beaujolois. “Everyone was praying for the return of good weather and holding their breath“. In the meantime, it was very difficult to identify each ship that returned to port. As with the Dieppe Raid, the Wrens displayed the word ‘Unknown‘ until they can spot the ships with the code. The Plot Map was then simplified by assigning coloured labels to convoys: yellow for those heading south, orange for the north, blue for warships.

OK, let’s go! On 5th June General Eisenhower made the decision. The real Zero Hour had arrived and the beginning of the operation was scheduled for 10 p.m. The next day, June 6th, at dawn, the huge armada was already in the middle of the Channel and was heading towards Normandy. Even if Beaujolois woke up knowing all about it, the operators who announced the news did not know what they were announcing because the messages were all coded. While all the ships in the world seemed to be heading for France to regain a foothold and crush the occupiers, Beaujolois was surprised that the Germans had not yet made their presence known. “Surprising,” she thought, “seeing such an accumulation of ships. They must surely be preparing something!” Then, in the middle of the day, she and her friend set off on their bicycles towards the coast. It was such a sight. Thousands of ships and planes marked with black and white stripes. The latter were going to support the ground forces charged with taking possession of the designated bridgeheads, the essential objectives of the first day of the landing. Beaujolois knew that their work on the Plot Map had been designed to help with the reconnaissance.

6 June 1944 – Operation Neptune – the seaborne part of Operation Overlord

She asked two soldiers to lend her their binoculars, but they refused, thinking that what she could discover was secret. But Beaujolois couldn’t tell them that she herself was already “in the know”! Her colleague Christian Gordon also realised that Operation Overlord is being launched from Portsmouth and not Dover, much to her relief. In the Operations Room the giant Plot Map that had been hitherto hidden was then revealed. Small red blobs representing the E-Boats could be seen. The new map had yellow lines marking the mine-free sea lanes across the Channel. There was also a yellow circle south of the Isle of Wight called “Piccadilly Circus”. From here, further yellow lines formed a sort of corridor called “The Funnel” which lead to the landing beaches where the minefields are marked. The work of the Wrens became more intense with the regular movement of ships and exercises of all kinds. From the mezzanine above the Plot Map, Admiral Sir Charles Forbes could look down and observe the map where the young women were busy. At a glance, he can see everything sailing towards France.

Normandy – 6th June 1944

By observing the handwritten annotations on the glass walls of the tunnels that morning, Beaujolois witnessed in real time the movements in the Channel, their destination and escorts, the time they unloaded their precious cargo and the time they disembarked the men onto the beaches and returned to England empty. She also saw the casualties among the crews, if there had been any wounded and any air attacks. She could see all the civilian and military ships, personnel, small coastal craft, and landing craft involved in the operation in a single glance. Those leaving and those returning were in different colours and the warships in blue. It even showed the volume of steam or smoke emitted and the speed at which it was moving.

Beneath the crest drawn made by the Wrens and representing them working along with the WAAF’s in the Plotting Room that day, Beaujolois Cavendish felt she had really accomplished her mission as a Wren.

Inside Fort Southwick Plot Room, Plymouth where the Wrens worked. In the background on the mezzanine, is the symbolic coat of arms designed by a Wren (Henry Gibson Gordon Collection)

Available 28th January 2022, Les femmes de la Royal Navy is available here:

also:

or by contact with the author on: echolorraine@orange.fr

Geneviève Moulard lives west of Paris and has published other books including:

Drones, mystérieux robots volants (co-author)

Les femmes de la Royal Air Force