In Love with the Resistance – Rosie Whitehouse

In love with the Resistance:

my mother-in-law’s war

by

Rosie Whitehouse

On a moonlit night in March 1944, three agents floated down on parachutes into the Languedoc highlands east of Castres, in southern France.

One was Pierre Haymann, a Parisian Jew who had been trained in sabotage and partisan warfare in the UK. The other was Bernard Schlumberger, a Protestant from Alsace, who was to be the Free French army’s envoy in the Toulouse region of south-west France.

Their brief was to unite the scattered local Resistance militias behind Free French leader Gen Charles de Gaulle, from a base in the tiny town of Vabre where they had been guaranteed protection by local partisans.

Operation “PAUL-9”: Charles Bernard Schlumberger, Pierre Haymann and Michel Couvreur dropped on their DZ (Drop Zone) “Chenier” at Saint-Saury on the border of Cantal/Lot on 18 March 1944. Objective: Schlumberger was to become head (Délégué Militaire Régional) of R4 (Lot et Garonne / Haute Pyrénées).

But before starting work, Pierre travelled 400km to the city of Lyon to find his girlfriend, Marion Müller, from whom he had been parted 15 months earlier.

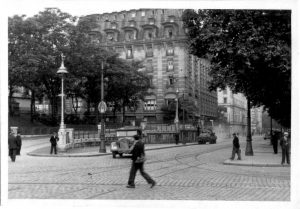

It was a risky journey as the SS in that city knew him well. Marion and Pierre were both members of the Resistance, and in 1942 Pierre had been captured and taken to the notorious Hôtel Terminus, where SS commander Klaus Barbie – the “butcher of Lyon” – tortured his victims.

Hotel Terminus, Lyon – 1941

Pierre managed to escape, but then had no choice but to flee over the Pyrenees into Spain in midwinter.

When they were reunited in 1944, Marion dyed Pierre’s hair red in an attempt to disguise him, but the paramilitary police soon tracked him down. There was a shootout, in which Pierre was injured, then the couple hurried to safety in Vabre.

Vabre – Department of Tarn in the Occitaine Region, Southern France (1930)

Today:

Michel Cals, a retired professor, takes me along a dead-end track that leads through the forest to Schlumberger’s former HQ outside the town. We pass a pretty farmhouse where 30 Jewish girls were hidden by the local Protestant pastor before they were smuggled into Switzerland. Then a large stone house comes into view, sitting on the brow of a hill.

The path was guarded at key points by the partisans, known as the maquis, after the French word for the southern scrubland where many such groups operated.

Next to the house there is a wide field with breathtaking views across the valley. It was ideal for parachute drops. I can imagine Pierre and Marion running out into the moonlit field to gather up the explosives, weapons and money that fuelled their battle against the Nazis.

Cals explains that the valley was like a fortress. “The Germans were based in nearby Albi and Castres but only had resources to send patrols into the valley,” he says.

France Regional Map 1943 showing “Occupied” and “Vichy Zone”

It was also perfectly located, reachable by planes flying from both the UK and Algeria, where Gen de Gaulle by this stage had his HQ.

Until recently, little was known about Marion’s wartime experiences. She was my mother-in-law, but brushed away all questions with a wave of her hand, and died in 2010 without telling the story.

The one scene she would describe was the dying of Pierre’s hair – she told us how she joked as she did it that if they had a child, it would have red hair too.

Last year Marion’s younger sister, Huguette, revealed how Marion had taken her to hide in the ski resort of Val d’Isère after their mother, Edith, was arrested in 1943 and sent to the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

There in the high Alps, 15-year-old Huguette broke her leg and as a Jewish escapee was treated by a brave French doctor who hid her for six months in his house.

The home of Dr Frédéric Pétri in Val d’Isère.

To find out more about this period in Marion’s life I went to the National Archives in Kew, West London, to read the yellowing papers in a once top-secret file on Pierre, who was trained as a saboteur by the UK’s Special Operations Executive. It was this that led me to Vabre – where Michel Cals and others explained how an unusual anti-Nazi coalition had been forged.

It was no accident that Schlumberger, a Protestant, had been paired with Pierre, a Jew. Vabre was a Protestant village with a Protestant maquis. But the hills around the town were the base of an exclusively Jewish armed militia group, which became known as the Compagnie Marc Haguenau. Schlumberger and Pierre would merge these groups together.

Bernard Schlumberger’s Resistance headquarters in the forest near Vabre

Marion always said that the people of rural France were insular and disliked anyone who was not from their locality – they wanted the Jews and the Germans alike to just go away. But Vabre, a grey-stone town on the banks of the fast-flowing Gijou river, was different.

It was a tight-knit community united behind its pastor, Robert Cook, in its opposition to the Vichy regime – the French government under Marshal Pétain, which collaborated with the German invaders – and was far from insular.

An industrial town, Vabre made its living weaving cloth that it sold to Jewish tailors in Paris. In July 1942, after the mass arrest of Jews in the capital, many tailors arrived with their families seeking sanctuary.

On the edge of the town is a large building known as the barracks. It was here that Louis XIV’s soldiers were billeted during the persecution of the Protestant Huguenots – ancestors of the modern population – in the 17th Century.

The people of Vabre had not forgotten how the state mistreated their forebears and did everything they could to help the Jewish fugitives, especially after an incident in the summer of 1942, when Vichy also began to round up Jews to hand over to the Germans.

On 26 August, the Vabre police were ordered to the nearby resort of Lacaune to arrest foreign-born Jews who had been interned there. Ninety were taken into custody, among them 22 children, all of whom were later murdered at Auschwitz.

The gendarmes from Vabre returned home in tears, and police chief Hubert Landes decided it was the last time he and his men would follow that kind of order. A year later he warned Jewish refugees of an impending overnight round-up, urging them to hide.

Many of the surviving Jews in the area joined the maquis.

Allied aircraft drop supplies for the maquis (1944)

image: Getty Images

Michel Cals has opened a small museum in Vabre dedicated to the Resistance. It is home not only to Schlumberger’s radio set, on which Pierre’s orders were received, but a mass of paperwork from the period and testimonies from the men who fought in the maquis. In the maquis register the names of local men are jumbled up with those of Jews born in Paris, Alsace and Eastern Europe. It is evidence of a remarkable unity.

The documents also reveal that Schlumberger’s strategy, railway sabotage, put Pierre centre stage. It was Pierre’s job to train the Compagnie Marc Haguenau to blow trains sky high, which he did throughout the spring of 1944. In June however, immediately after D-Day, he was sent to train maquis further north.

He and Marion moved to Cahors, where he took on a formidable enemy fresh from the Russian front – the Second SS Panzer Division, known as Das Reich – who were moving north to support the German army in Normandy. But the sabotage carried out in this region came at a high price; in revenge Das Reich massacred 642 villagers, including 205 children, in Oradour sur Glane. (https://afheritage.org/the-man-with-the-white-handkerchief-caroline-broch)

Pierre’s training also helped the Vabre maquis to carry out a dramatic attack on a German supply train heading for Castres on 19 August 1944. In the fierce shoot-out, the Compagnie Marc Haguenau suffered severe losses before the Germans finally capitulated. The maquisards asked their German prisoners, “Do you know who we are?” They were shocked when each of their captors announced in German, “Ich bin ein Jude!” – “I am a Jew!”

Castres, August 1944: Members of the Maquis de Vabre arrive on a lorry

image: Alamy

The same men then took part in the liberation of Castres, taking a further 3,500 German prisoners.

Marion was 20 when she met Pierre in 1940 – he was 25. As a soldier in the French army, Pierre had been held in a POW camp, but escaped, crossed the demarcation line into Vichy France and arrived in Lyon.

The Resistance network they helped to build there was one of the first that was committed to military action.

When Pierre made his midwinter trek over the Pyrenees to Spain, Marion did not accompany him, as she feared she wouldn’t make it. However, it meant she faced the most dangerous months of her life alone.

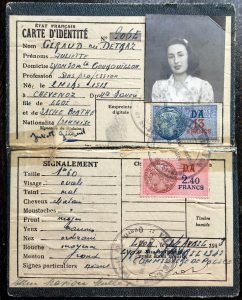

Marion’s false papers, in the name of Juliette Giraud

It’s likely that she was often alone in Vabre too, as Pierre spent time away with the maquis.

After they arrived in Cahors, she had a narrow escape when a barman told the Germans she was suspicious. So she parted from Pierre again to return to Val d’Isère, for a reunion with Huguette.

Once again, she was alone and in danger. At one point on the journey German soldiers offered Marion a lift. She wisely refused. Later, she discovered the SS were picking up young girls, raping them and then throwing them from the walls of a nearby castle into a ravine.

The two sisters arrived in Toulouse just before the city was liberated on 19-20 August 1944.

Now pregnant and exhausted, Marion was forced to rest before she and Pierre could travel to Paris. It meant they missed out on being allocated the best of the apartments of former collaborators that were given to Resistance leaders. It irritated her all her life that they arrived too late for a flat on the Champs du Mars with a direct view of the Eiffel Tower.

That autumn, Pierre and Marion married. Soon after, Marion gave birth to a daughter – who, as she had predicted, had red hair. They had a second baby, a son, but the marriage did not last. Marion always said they were simply too young, but perhaps they had spent too much time apart to build a life together?

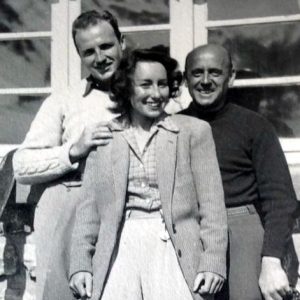

Marion Müller

Marion eventually married again, moved to London and had a third child, who is now my husband.

World War Two divided France, and after the liberation most people chose not to speak about the war years for fear of opening old wounds.

In Val d’Isère, where Huguette sheltered with her broken leg, the silence continues today.

In Vabre things were quite different, though. From the first anniversary of the liberation, the locals celebrated the story of how Protestants and Jews took on the Nazis.

Michel Cals thinks Vabre’s unique story deserves to be heard more widely. “It is a lesson in morality and that you must help those in need,” he says.

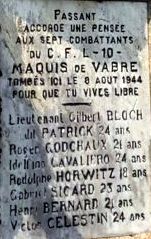

Michel Cals, standing by a memorial to fallen members of the maquis.

Thanks to his work, Yad Vashem (The World Holocaust Centre https://www.yadvashem.org/) recognised Vabre as a “Town of the Righteous” in 2015, and this month police chief Hubert Landes will join Pastor Robert Cook on the list of righteous individuals.

The spirit of Vabre’s resistance has left its mark on France. Catherine Vieu-Charier was born and brought up in Vabre. The moment she walks into the cafe, I am struck by the Hebrew tattoo on her wrist. It is the name of her late partner, Henri Malberg, a well-known Parisian politician. In 1942, he and his family had escaped capture in the notorious Vel d’Hiv (Winter Velodrome) roundup in Paris but were later interned by the Vichy government.

In 1995, Vieu-Charier and Malberg, both communist activists, launched a campaign to identify and remember the Jewish children who were deported from Paris by placing plaques on the city’s schools. It was an idea that rapidly spread across France. One of these plaques sits on Huguette’s former school in Nice, commemorating 16 of her fellow pupils, who were gassed in Auschwitz.

Vieu-Charier and Cals are fearful that the story of civilian Resistance in Vabre will be forgotten and are working to make sure it takes its place alongside the celebration of what Cals calls the “testosterone story of men with guns”. Both their families hid Jews but never talked about it because they regarded it as their humanitarian duty, Cals says. “They never bragged about it and just got on with their lives.”

Vabre Maquis Memorial Plaque

Their work has already begun to bear fruit. Cals was at the forefront of a campaign to welcome Syrian refugees to Vabre. Just before the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown the first Syrian family arrived. Two others have since followed. The message is that it is not enough to simply allow strangers to stay in the village but that they need to be accepted as equals and integrated into local life.

The original maquis register that lists the names of Protestants and Jews all jumbled up together stands as testament to that.

Rosie Whitehouse is the author of “The People on the Beach: Journeys to Freedom After the Holocaust”.

Unattributed images: Rosie Whitehouse & AFHG/GPFA

AFHG French Translation by Geneviève Monneris: https://afheritage.org/amoureux-de-la-resistance-la-guerre-de-ma-belle-mere-par-rosie-whitehouse

AFHG Production: Ian Reed

What a interesting part of history and the what the resistance did to help shorten the war.