Why We Remember Remembrance – – – Ian Reed

A brief look at the history, symbols and the relevance of Remembrance and why it is still important today.

Version francais cliquez ici: francais

Stopping the Cycle of War

In 1859 Austria invaded Sardinia and fought against France (11 weeks), in 1864 Prussia and Austria invaded Denmark (9 months), in 1866 Prussia invaded Austria (5 weeks) and in 1870 France declared war on Prussia (6 months).

In all these wars the outcomes came within just a few weeks or months. Reparations or land transfers were duly paid by the losers, then everyone went back home and prepared for the next war.

This had gone on for centuries. A Roman general once famously expressed, “the intelligence of Man has never changed – only machinery improves”.

So it was that by 1914 some of this generation still thought along the same basic lines, except that this time weapons manufacture had improved dramatically and the two opposing forces were so equal that a stalemate resulted in static trench warfare which lasted 3¼ years (39 months), in which millions died.

French Soldiers advance during the Battle of Verdun (21 February to 18 December 1916) in which there were almost 1 million casualties during 10 months of fighting. One of the longest and costliest battles in history.

On 11th November 1918 the guns eventually fell silent to mark the end of hostilities between the nations of the Allied (or Entente) Powers and The Central Powers, during what was then named The Great War.

The guns had stopped because of an agreed “cease-fire” – an Armistice – not a clear victory. In fact German soldiers on the Front Line were not beaten and in most cases were in strong fighting positions, and many were “incredulous that everything stopped so suddenly!” The subsequent feeling of unfairness in the crippling reparations made against Germany by the peace treaties was one of the overriding reasons which gnawed into the German sub-consciousness and motivated them into a second, more deadly, international conflict only 20 years later.

Whatever the reasons to go to war, the real cost in the lives of ordinary civilians and, mainly conscripted, armies was too much. The increasing democratisation of the world’s major nations now meant that all powerful heads of state were no longer able to direct their nations’ politics. Every voter now had a say, and the people wanted this cycle stopped.

Symbols to Remind Us All

A Human Failing. The creation of major recognisable symbols against the carnage of modern warfare began to be established even before the “War to End All Wars” had ended. It was a recognition that successive generations never really learn from their predecessors and the term “We Will Remember Them” was a way in which each generation verbally passes down to the next, how so-called civilised nations can so easily decline into barbarism and destruction of their people. A lesson as relevant today as it was then.

The Unknown Warrior

Temporary graves of unknown British soldiers on the Western Front

Following World War 1, the sorrow and outrage of the huge death toll of the nation’s youth was unimaginable, but it was also the knowledge that the type of warfare now waged destroyed human beings at an industrial level. It gave rise to the symbol of “The Unknown Warrior”, and for Britain this was to recognise the 517,773 sons, brothers, fathers, uncles or friends whose bodies had either been totally destroyed or were no longer recognisable to be identified or given a proper burial.

British Army Chaplain Rev David Railton (1884-1955)

In 1916 the Rev. David Railton, serving as an Army Chaplain on the Western Front conceived the idea of recognising this fact when he noted the numbers of burial crosses marked “Unknown”. He suggested that one of these unknown soldiers should be “buried alongside the Kings of England” at Westminster Abbey, and eventually plans were drawn up make this happen. On the night of 7th November 1920, the body of one unknown British soldier was randomly chosen from the many at a special ceremony at Saint Pol-sur-Ternoise near Arras .

The Coffin of the British Unknown Warrior escorted by French troops – November 1920

A coffin containing the remains of a British soldier was escorted to Boulogne by the entire French 8th Infantry Regiment who stood Honour Guard overnight. The next day it was taken in a mile long procession accompanied by over a thousand French schoolchildren, French cavalry and troops, to where Marshal Foch (Supreme Allied Commander), took the salute before the coffin was loaded onto the destroyer “HMS Verdun”, bound for England.

HMS Verdun embarks from Boulogne Harbour – 8th November 1920

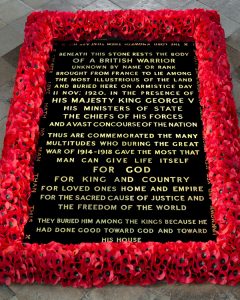

On 11th November 1920 the coffin with the Unknown Warrior was carried in procession on a horse drawn gun carriage through Central London followed by King George V and the Royal Family and placed inside and near to the entrance of Westminster Abbey, where it lies today.

The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, Westminster Abbey, London.

On the very same day France brought their selected Unknown Warrior from the battlefields of Verdun to the chapel beneath the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and two months later it was laid to rest in the centre of the Arc where it resides today.

On 11th November 1921 the United States buried their Unknown Warrior at the Memorial Amphitheatre, Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The tomb of the French Unknown Warrior beneath the Eternal Flame – Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

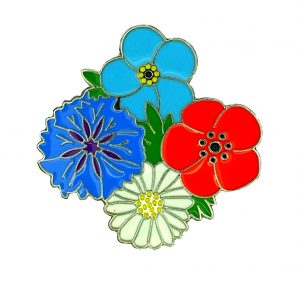

The Flowers

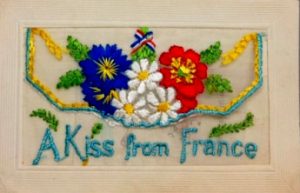

During the Great War postcards from the battlefields had often used three flowers, namely the poppy, cornflower and the daisy which had grown amongst the devastated countryside.

Cornflowers, Daisies and Poppies on an embroidered greeting card sent from the Western Front in 1918

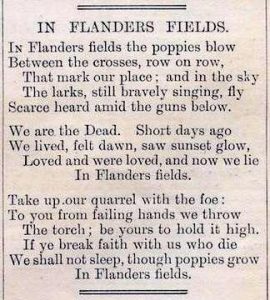

1/. “Flanders Poppy”

Bombs, artillery shells and mines which had exploded over the fields of Northern France and Belgium for 3¼ years had destroyed most things on the surface. It unearthed millions of tonnes of soil and exposed ancient plant seeds, which then bloomed in abundance where nothing else grew. The imagery of the thousands of red poppies (papaver rhoeas) covering the battlefields was not missed by the people who witnessed it. It seemed to exactly reflect the blood and carnage which had taken place and was expressed so emotionally by Canadian Army physician, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae’s 1915 poem ‘We Shall Not Sleep’ later named “In Flanders Fields” written before he died at the British General Hospital in Wimereux in January 1918.

Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae (1872-1918)

McCrae had initially dismissed the poem but it was retrieved by a colleague and on 8th December 1915 his poem was published in ‘Punch’ magazine. By 1916 it was appearing in regional newspapers and soon afterwards “Poppy Days” began to take place across England, particularly in the North East and Yorkshire where significant numbers of British Army troop recruitment had taken place. Pressed flowers were often sent home from the trenches and the symbolism of the red poppy became embedded into the connection with the war in France. Soon after, the poppy symbol began to appear across the British Empire & Commonwealth and in the USA. Lectures and fund-raising “drives” for the injured and orphans were commonplace, and the poppy began to symbolise them all.

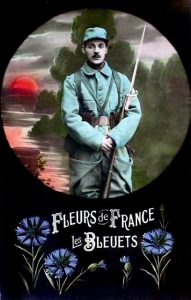

2/. The “Bleuet”

It is perhaps ironic that the promotion of the Flanders Poppy had been driven by a French lady and an American lady of French descent yet in France the cornflower or “bleuet” is the French national symbol of Remembrance.

The pale blue cornflower matched the “bleu horizon” colour of the uniforms of the new French conscripts of 1915 (most under 20 years of age) who were quickly recruited to shore up the huge casualties initially suffered by the French Regular Army who still wore the traditional French dark blue uniform with red trousers. These new fresh troops were soon labelled, “Bleuet’s” and the name stuck.

The use of the Bleuet (centaurea cyanus) as a badge of French national remembrance was created in 1916 by Charlotte Malleterre and Suzanne Lenhardt, head nurse at Hotel Les Invalides national military hospital in Central Paris. Suzanne Lenhardt was the widow of an infantry captain killed in 1915, and sister of Général Gustave Léon Niox. Madame Malleterre was the wife of Général Gabriel Malleterre.

A fabric “Blueut” sold by Souvenir Francais during Annual Remembrance

They organized workshops to manufacture the Bleuet cornflower badges from paper and sold them at public events throughout the war. The money was used to support ex servicemen, and after the War the Bleuet began to be recognised nationally following its adoption on 15th September 1920 by the Mutilés de France (The Injured of France) and the Federation Interalliee des Anciens Combattants (Veterans Affairs) as the “eternal symbol” for all those who had died for France.

Today the Bleuet is still a recognised symbol of French Remembrance and although the physical Bleuet has changed in appearanbce several times, it is still sold in large numbers each year, even in the UK.

3/. The “Margriets” Daisy

Even before the Great War, people in Belgium and the Netherlands already used the large white daisy or “madeliefje” as their symbol of mourning and this continued throughout the Great War. During WW2 it was used as a symbol of “resistance” against German Occupation and the Dutch Royal family emphasised this during their exile from the Netherlands in London by wearing the daisy, colloquially known as margriets in Dutch.

The “madeliefj” symbol of Remembrance across Belgium and the Netherlands

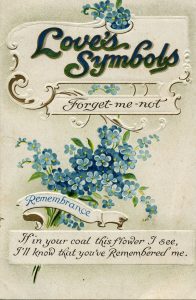

4/. The “Forget-Me-Not”

The small blue flower (Myosotis arvensis) is common throughout Europe. It’s name in English comes from the German “Vergissmeinnicht“ and is the symbol of remembrance used by the people of Newfoundland and Labrador (which was an independant dominion during the Great War) to commemorate those who were killed in the First World War.

The 1st Newfoundland Regiment fought with distinction but was almost completely destroyed with 91% killed or injured at Beaumont-Hamel on 1st July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The regiment continued with honours in several further engagements being the only regiment to receive the prefix “Royal” from HM King George V. As a Dominion of Britain, Newfoundland officially joined with Canada at midnight on March 31, 1949.

The Forget-Me-Not is also used in Germany to commemorate the fallen soldiers of both world wars.

5/. Natalie’s Ramonda.

Natalie’s Ramonda (Ramonda nathaliae) was named in 1884 after the Natalija Obrenović, Queen of Serbia (1882 to 1889). It has rounded crinkled leaves with clustered purple flowers. As a pre Ice Age species it is acknowledged as one of the most rare species of Europe and is endemic in Serbia, Macedonia and Greece, in the Western Balkans. It is strictly protected in Serbia and is still recognised as the flower commemorating the huge losses suffered by the Kingdom of Serbia, which fought alongside the Allies during WW1 and lost one third of its entire male population between 1914 and 1918.

Natalie’s Ramonda – the Remembrance flower of Serbia

” Selling the Flanders Poppy”

Although generally accepted today as the symbol of Remembrance in the English speaking world, it took time, effort and organisation by a relatively small number of people, to become established. These people worked tirelessly to promote and sell these symbols of war suffering for the benefit of those who had suffered most.

Anna Guérin “The Poppy Lady of France”

In August 1914, Madame Anna Alix Guérin (née Boulle), was a 36 year old lecturer on French art and history. An Officier d’Académie (Silver Palms), she initially worked on behalf of Alliance Français, and became known as “the greatest of all the war speakers”. She was a passionate and highly motivated young woman who inspired the people who heard her.

Anna Guerin – “The Poppy Lady of France”

When war broke she had been in Britain for four years. A prolific lecturer and speaker on the subject of French history and culture for Alliance Français, she had travelled to hundreds of speaking engagements over the breadth of the UK. She had already agreed to take her lectures to the USA before war had broken out, and in October 1914 she boarded the RMS Lusitania and sailed to New York where she then travelled thousands of miles across the USA giving stirring patriotic speeches in support of the Red Cross and Allied causes. Often giving over 60 speeches at events in a single town or city, she became a well known and popular personality. Before the USA had joined the War and was still “neutral” she was already receiving discreet donations towards many French charities in support of orphaned children in France. She regularly returned to France and in mid 1916 she helped out as a nurse for a short period where she experienced the horrors of modern warfare. She found the experience traumatic and returned to the USA where she believed her lecturing skills could be put to better use in appealing for support and funds for the orphaned families of the French Children’s League.

Anna Guerin (in aeroplane cockpit) during an Inter-Allied Poppy Day.

Anna Guérin continued to travel thousands of miles across America and undertook hundreds of lectures and appearances at Poppy Day events in the USA and Canada from 1916 until 1921. She sailed back to Britain in August 1921 where she promoted the idea for the British Legion to adopt her “Inter-Allied Poppy Day”. By September, British Commonwealth and USA ex servicemen’s associations had all adopted the poppy as their official national memorial flower.

She had organised widows and orphans in France to manufacture fabric “poppies” for sale to raise funds and even offered to cover the initial costs of production herself to help it begin. Her efforts produced large sums of money which were used in hundreds of large and small projects across France to assist the survivors of the war torn country.

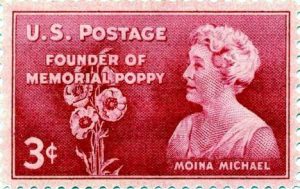

Mrs Moina Belle Michael (1869-1944)

Following the entry into the War by the USA in April 1917 an American academic of French Hugenot descent, Moina Belle Michael (who had been in Germany when war had broken out) decided to take an unpaid leave of absence from her teaching profession to help YMCA overseas voluntary workers in their war effort. She had been so inspired by John McCrea’s poem of 1916, that she took to wearing a poppy and immediately after the War ended she published a successful response entitled, “We shall keep the faith”.

She began working to raise funds to support disabled ex servicemen, and began to sell Madame Guerin’s silk poppies to raise funds. By 1921 she promoted the poppy symbol for acceptance by the American Legion Auxiliary and influenced the official acceptance of the symbol by others.

Major George Howson MC

With the successful sale of Anne Guerin’s poppies in Britain during 1921, the British Disabled Society under the chairmanship of Major George Howson MC (awarded for service at Passchendaele 1917), established the Poppy Factory in 1922. It supplied the British Legion – Earl Haig Fund (Field Marshal Haig- Commander of the BEF 1915-1919) with artificial poppies made by disabled ex-servicemen at a factory in the Old Kent Road in London, and in its first year produced over 15 million poppies. The next year it merged with the British Legion (today The Royal British Legion), and with personal financial support from Howson, it moved to larger premises in Richmond Surrey where it is there to this day, operated by disabled ex-service personnel. In 1926 another factory was established in Edinburgh under the auspices of “The Lady Haigh’s Poppy Factory.

The Poppy Factory, 20 Petersham Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW10 6UR.

www.poppyfactory.org – +44 (0)20 3376 8080 – info@britishlegion.org.uk

Major Howson with workers at the Poppy Factory

In Conclusion

If humanity is incapable of learning from previous generations until it has experienced it themselves, and every subsequent generation thinks itself culturally superior to its predecessor, then history soon shows us that it can eventually make the same mistakes and, as technology increases, the effort to prevent war is often matched by the will to wage war.

Where war becomes politically “inevitable”, whether you are an ordinary civilian, a conscript or regular military personnel, everyone “pays the price”, and it is because of this that we need to constantly remind ourselves of what can so easily happen. The symbolism of the Great War of 1914-1918, whilst over 100 years ago, is still so very relevant in reminding everyone today that we are all responsible to ensure that the sacrifices and lessons gone before us were not in vain.

We Shall (and we must) Remember Them

Please Donate to the British Legion Poppy Appeal:

https://www.britishlegion.org.uk/get-involved/ways-to-give/donate

Click here/Cliqez ici:

In Flanders Fields – recited by Dame Helen Mirren at Ypres in Belgium on the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Passchendaele – +500,000 casualties.

Ian Reed – 1st November 2020

Version in French here: https://afheritage.org/pourquoi-se-souvenir-du-souvenir-ian-reed

An excellent history lesson,, so important to remember. Thank you

Very good lesson for never forget HISTORY.

A really excellent piece, thank you.

Would you allow me to copy it and circulate it to our Members, citing your copyright.

Regards

Duncan

Chairman. Bordeaux & SW France Branch,. The Royal British Legion.

Yes please Duncan, by all means.

Thank you Ian, an excellent piece!

I shall forward on social media to my 4,800 followers of all nationalities.

A very interesting, poignant piece. Thank you.

Very interesting Ian, thank you.

So sad we will not be in Elvington for Remembrance Sunday

Alain MALLIA

As poignant as it is informative. An excellent article Ian, thank you.